A map of San Sebastián de La Gomera town at the end of 16th century, by engineer Leonardo Torriani (source: Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra, catalogue number Ms. 314, fol.83v.).

[…] old Chupulapu[…] told them crying, and repentant, I shall die soon so there you stay, who will pay well Lord Peraza’s death, woe to your children, and families, woe to you miserable ones, and soon after he died;[1]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

Tomás Marín de Cubas (Historia de las siete islas de Canaria –1694–, Book II, Chapter XII)

The dramatized end of Pablo Hupalapu, or Chupulapu, in the story shared by both Abreu Galindo and Marín de Cubas, preludes the atrocious reprisal that Gomeran people would suffer at the end of 1488 or the beginning of 1489 after the death of Fernán Peraza the Younger at the hands of his own vassals.

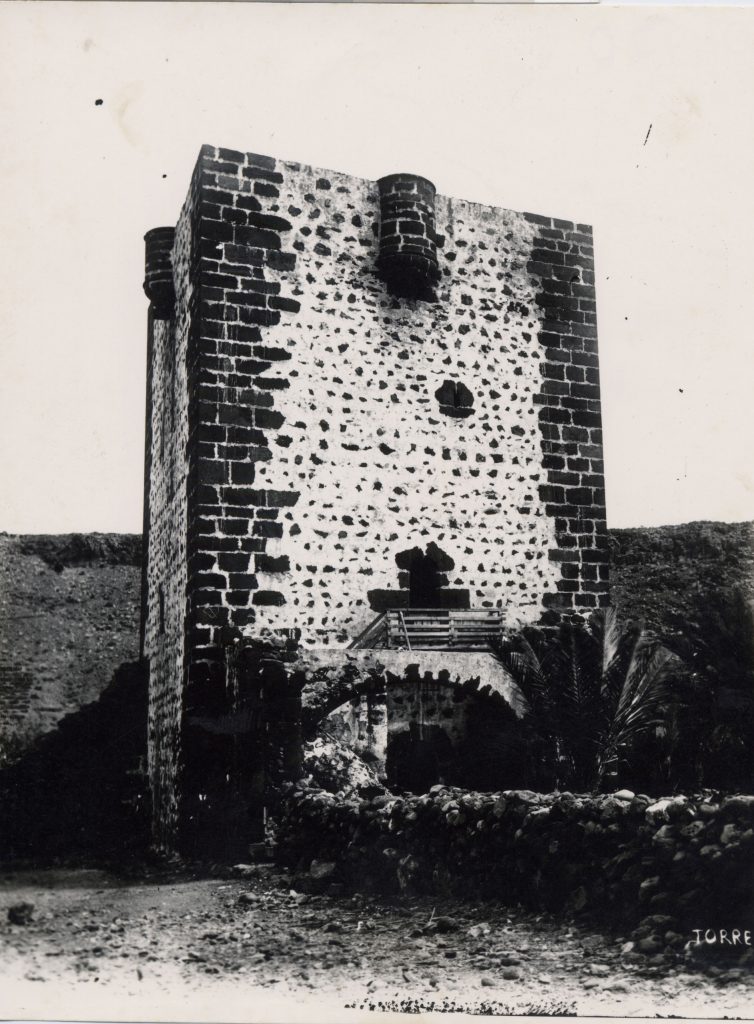

After finishing the life of the Castilian Lord of La Gomera, the rebels tried to take the Tower of San Sebastián –known nowadays as Torre del Conde, southernmost medieval European fortress– now a refuge for the widow, Beatriz de Bobadilla, and her two small children, Guillén Peraza de Ayala –future first Count of La Gomera– and Inés de Herrera. According to both historians, Pedro Hautacuperche himself, Peraza’s killer, led the assault, dodging, and even picking up with his hands the defenders’ crossbow shots. But the exhibition of the indigenous leader ended up costing him his life, because while Notary Antonio de la Torre distracted his attention with projectiles from the fortress’ flat roof, Alonso de Campo, stationed behind a lower arrow hole, gave him a deadly impact with a bolt propelled by a powerful pulley crossbow. Once Hautacuperche fell down, the attackers retired, a circumstance that Gomerans belonging to the Orone tribe, loyal to the Castilians, certainly took advantage of to deliver Peraza’s corpse to the widow, and the latter to ask for help abroad.

“and do neither consent nor give any chance the residents on the said islands to give up her due obedience” (source: Archivo General de Simancas, catalogue number RGS, LEG, 148903, 300).

The two letters

Although the chronicle sources simply state that Beatriz de Bobadilla had Pedro de Vera, Governor of Gran Canaria, called directly to help her, public documents suggest a more complex course of events: in March 4th, 1489, from Medina del Campo, the Catholic Monarchs simultaneously dispatched two letters addressed to the Jerez-born Captain. One of them shows that in fact it had been Inés Peraza, mother of the deceased Lord of La Gomera, who had formally denounced the murder of her son before the monarchs, demanding justice:

[…] some residents on an island […] killed Ferrand Peraça, her son [of Inés Peraza], and have rosen up and want to rise up […] and either want or shall want to give up her due obedience which if it were to happen she says she would take grievance and harm.[2]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

All in all, the second letter becomes interesting because, although it responds to a request for help made by Beatriz de Bobadilla, it suggests that her main fear was not the rebellion but that some people –undoubtedly, her mother-in-law and siblings-in-law– could dispossess her of her rights as mother and guardian of her children. In fact, Fernán Peraza’s demise is mentioned in it almost anecdotally, not even sketching the circumstances in which it happened:

And that due to the death of the said Ferrand Peraça her husband to her said children belong the said islands and to her as both their mother and guardian and that she fears and suspects that some persons will want either to take from her and occupy the possession of the said islands […] or will seize the possession of them which if it should happen she says great grievance and harm would be taken […][3]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

But another official document, dated in 1491, certifies that Bobadilla had directly requested Pedro de Vera’s help. Specifically, the response of the Crown to a letter sent by some residents on Gran Canaria who participated in the reprisal, and who demanded Pedro de Vera the payment of their wages on the matter, since the Governor had paid them in slaves who were requisitioned later for having been subjected to illegal selling, as we shall see. The answer claims that:

[Beatriz de Bobadilla] had requested help, to [go] against the said Canarians, from Pedro de Vera, Governor of the said island of Grand Canaria, […][4]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

In any case, the fateful order given by the Catholic Monarchs to Pedro de Vera in the first of the letters leaves no room for interpretation:

[…] we command you […] to protect and defend on the possession of her said islands the said doña Ynés and do neither consent nor give any chance the residents on the said islands to give up her due obedience, […]and to do justice to the criminals give her and make to give her all favor and help she could request from you and have need of, and either on that matter or part of it do not consent either any hindrance or opposition to be put in against her.[5]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

If we take for certain the date of beginning of the rebellion deducted from some ethnohistorical sources –as we pointed out in the first part, on November 20th, 1488–, the time elapsed between this date and the beginning of the repression seems to be excessive, assuming it was carried out after the issuance of the aforementioned letters, in March of 1489. However, Bobadilla herself gives evidence to certify that Vera landed at La Gomera after some delay, when she declared before the Royal Council that the Gomerans had had her sieged for a long time, although it is plausible that, even so, the said intervention might have occurred before March.

The Tower of San Sebastián also known as Torre del Conde (Tower of the Count), between 1890-1895 (source: José A. Pérez Cruz Collection / FEDAC).

In blood and on gallows

The Catholic Monarchs knew perfectly well the man they were sending to crush the uprising, the colonial authority nearest to the conflict zone. A mastiff –in the words of his own son, Hernando de Vera– holding an extensive list of services rendered to the Crown of Castile and the Seigniory of Marchena, whose last line included the final submission of Gran Canaria to the monarchs after five years of harsh war. He fed his extensive military and administrative experience with an expeditious and unscrupulous personality that had led him in times, even, to face the authority of two untouchables of the Kingdom: Don Juan de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, and Don Juan Pacheco, Marquis of Villena.

Most of well-known sources coincide in that, on an indeterminated day and month, Pedro de Vera disembarked on La Gomera at the head of four hundred men, and after freeing the widow and children of their seclusion, and in view of the fact that the conspirators had ran away, he ordered to celebrate the funeral rites for Fernán Peraza and proclaim that anyone who would not attend would be declared guilty ex officio.

Then, Vera ordered to arrest all attendees, both to avoid a new riot and to leave the real culprits without any chance of refuge and support. From the interrogations carried out, it was concluded that the executioners belonged to Ipalan and Mulagua sides, and that they had fortified themselves in Garagona –in all probability, in the present Garajonay National Park–, where the Jerez-born one commanded his troops afterwards to demand the rebels to surrender and plead their defense. Having the latter rejected the ultimatum, Vera and her men entered the area, killing anyone who opposed resistance and detaining the rest. That was the beginning of a nightmare whose memory, we suppose, would remain in the survivors and their offspring for several generations, to the point that the current toponymy retains a name, supposedly related to the events: Llano de la Horca (Gallows Plain), in San Sebastián de La Gomera.

After a judicial process that we suppose very brief, and of which no documentary evidence has yet been found, Pedro de Vera ordered the immediate execution of all male Gomerans over fifteen years old, belonging to the sides involved. Let us leave the account of the massacre to the author of the Chronica Ovetensis, in chapter XXIV:

[…] since the killers were few, those condemned to death were many, and some were dragged and quartered[,] after being dead they cut their feet and hands, and some others who were alive they cut them, and some others were hanged, and some others with their feet and hands tied down were thrown and with weights around their throats they threw them into the sea, and those who did not reach fifteen years old they gave them other arbitrary [punishments] to Governor Bera’s liking[…][6]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

It is almost certain that the reprisal also reached men belonging to the other two sides, since individuals who were not executed but deported to several places are known. Those who had Lanzarote as their final destination fell to the wrath of doña Inés Peraza, who ordered to thrown them into the sea, according to Marín de Cubas. In this author’s opinion, La Gomera was then more depopulated than peaceful, while Historian Pedro Agustín del Castillo estimated the number of executions in more than five hundred.

The bloodshed not only soaked the seigniorial island: on his return, Pedro de Vera commanded to execute the same punishments on the Gomerans residents on Gran Canaria on the charge of having instigated Fernán Peraza’s death. Although this sentence may have had some evidence to support it –remember that some of the Gomerans living on Gran Canaria had been sold as slaves in 1477 by Peraza, among them, the chief of Mulagua side–, it is unquestionable that Vera would not have acted otherwise, as he could not afford the risk of a rebellion impelled by feelings of revenge, and in his own domain. The chronicles add a curious folklore episode: the thaumaturgical adventure of Gomeran Pedro de Aguachioche, a resident on Gran Canaria, two or three times saved from dying at the hands of the executioners, according to himself, by the intervention of St. Catherine.

On the left, Pedro de Vera imagined by draftsman Salcedo in a lithography by Rubio, Grilo & Vitturi editors for the Crónica de las Islas Canarias, by Waldo Giménez Romera (1868). On the right, the sepulchral effigy of the Bishop of Canaria, Brother Miguel López de la Serna, comissioned by the Catholic Monarchs together with the Bishop of Málaga, Pedro Díaz de Toledo, to rescue the Gomerans enslaved by Vera and Beatriz de Bobadilla (source: Memoria Digital de Canarias / Antonio Rumeu de Armas).

Enslaved and deported

Not fully satisfied with the massacre, Pedro de Vera and Beatriz de Bobadilla did not miss the opportunity to take advantage of the tragedy, selling all the women and children under fifteen belonging to the sides accused of the assassination. The Catholic Monarchs approved the drastic action initially, and a proof of this is the letter that King Fernando sent to the Governor of Ibiza in July 1489 authorizing the sale of ninety-one captives because, according to the sender, they had been condemned for being heretics and for some malice they committed against their lord. But, undoubtedly, this response from the Catholic King was the product of his impatience and thoughtlessness probably awakened by the insistent demands of either the dealers as well as the Balearic officials, as the monarch decided to resolve the matter expeditiously and unappealably from his royal camp during the siege to the city of Baza, whose capture opened the road towards the end of the War of Granada.

For, as it happened in 1477 with Fernán Peraza, this latter consequence of the mission entrusted to Pedro de Vera by the monarchs put the Castilian throne in a serious commitment, determined as it was to increase its prestige as an entity defending Christianity, with the added inconvenience that this time it was a royal commissioner who was violating the law, not an unruly nobleman. Carrying out all kinds of bloody ways to kill common people that would have ended the life of their natural lord was perfectly legitimate from the jurisprudence of the different European kingdoms, but, as we know from the second Alphonsine Partida, it was absolutely forbidden to enslave people who professed, at least officially, the same religion their captors did.

It is unknown who reported this illegal trafficking of human beings, although the ethnohistorical sources claim that it was don Juan de Frías, Bishop of Canaria, whom is said that Vera, after justifying his actions claiming that those were not Christians but children of some backstabbing traitors who killed their lord, and wanted to rise and take the island, threatened him to put a burning helmet on his head if he ever interfered in the case. True or not this confrontation, the fact is that Frías had died before the events, and the episcopal chair at that time was occupied by Brother Miguel López de la Serna. Thus, on August 27th, 1490, from Córdoba, the Catholic Monarchs ordered the bishops of Málaga –Pedro Díaz de Toledo– and Canaria –López de la Serna– to investigate the whereabouts of the captives and proceed to their immediate release:

Be known how due to certain insult some residents on La Gomera did and committed against Fernand Peraza […] killing him as they killed him in riot and fuss, Pedro de Vera, our Governor of Grand Canaria, went to the said island to favor and help Dª Beatriz de Bovadilla, […] and taking revenge on the said death they killed many of the residents on the said island of La Gomera and the women and maidens and boys and girls they captivated and sold them as slaves in many parts in our Kingdoms of Castile and Aragon. And because we were afterwards reported the said women and boys and girls were christians before and at the time their husbands committed the said crimes and that they had no charge or offence to be taken as slaves and sold as captives,[…] we command you […] to pick up all Canarian males and females from the said island of La Gomera you might find under any person’s power […][7]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

López de la Serna died two months after the order was issued, leaving Díaz de Toledo leading the investigation by himself.

In order to face the foreseeable economic claims by the buyers of the slaves to be released, Pedro de Vera and Beatriz de Bobadilla were ordered to deposit a bond in the amount of 500,000 maravedis, each one, with an additional guarantee in their personal assets. The governor obeyed, not without some protest, but Bobadilla refused to disburse the amount without first defending herself before the Council of Castile. She did so, arguing in her favor that selling the Gomerans had been legitimate, because they did not behave like true Christians and, after breaking certain pacts with Fernán Peraza, had conspired to kill the seigniorial couple and their children.

A long trial

The release of the captives, which surely remained unfinished, was carried out by means of a long and difficult police investigation to locate the victims, to demand from the buyers the liberation of the slaves and to restitute their economic investment.

We know the investigations, although carried out for the most part in the triennium 1490-1492, reached at least the year 1502, leading to the opening of a considerable number of files, as we can see by means of a simple search in the records of the Archivo General de Simancas through the PARES website, which is a sign of the political importance the Crown of Castile bestowed on the case, disregarding humanitarian considerations, little or nothing relevant at all in the social context of the time. One of its consequences was the dismissal of Pedro de Vera in 1491 as Governor of Gran Canaria, replaced by inquirer judge Francisco de Maldonado, although this setback did not lead him to completely lose the confidence of the Catholic Monarchs, who entrusted him with new missions in the last stages of the War of Granada, despite his advanced age.

References

- Abreu Galindo, Fr. J. de (1848). Historia de la conquista de las siete islas de Gran Canaria. Santa Cruz de Tenerife (España): Imprenta, Lithografía y Librería Isleña

- Arias Marín de Cubas, T. (1986). Historia de las siete islas de Canaria. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (España): Real Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País de Gran Canaria

- Castillo y Ruiz de Vergara, P. A. del (1848). Descripcion histórica y geográfica de las islas de Canaria. Santa Cruz de Tenerife (España): Imprenta Isleña

- Ladero Quesada, M. Á. (1968). “Las coplas de Hernando de Vera: un caso de crítica al gobierno de Isabel la Católica”, Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos, vol. 1, núm. 14, pp. 365-381. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (España): Cabildo de Gran Canaria

- Morales Padrón, F. (1978). Canarias: Crónicas de su conquista. Sevilla (España): Excmo. Ayuntamiento de Las Palmas – El Museo Canario

- Rumeu de Armas, A. (1969). La política indigenista de Isabel la Católica. Valladolid (España): Instituto “Isabel la Católica” de Historia Eclesiástica

- Wölfel, D. J. (1933). “Los gomeros vendidos por Pedro de Vera y doña Beatriz de Bobadilla”, El Museo Canario, vol. 1, núm. 1, pp. 5-84. Madrid (España): El Museo Canario