A pintadera made by ancient Canarians kept at Museo de La Fortaleza, Santa Lucía de Tirajana, Gran Canaria (source: PROYECTO TARHA, 2016)

It is usually argued that after the conquest of each of the Canary Islands, especially after the campaigns undertaken by the Crown of Castile itself in the cases of Gran Canaria, La Palma and Tenerife, the new, imposed political, legal and administrative order was configured in such a way that the original inhabitants enjoyed the same rights and freedom as the other subjects of the kingdom, as long as they embraced Christianity and submitted themselves to the authority of the Castilian throne, a consideration officially included in documents such as the already exposed Letter of Calatayud. Nevertheless it is well known that the new colonial regime discriminated against and marginalized most of the indigenous population compared to the European one, especially those individuals and family groups that actively or passively refused to collaborate with the invaders during and after the occupation war.

What is not so well known is that this phenomenon did not always occur in a hidden way, due to the spontaneous attitude of the settlers towards the Canarians, as one would expect from such a cultural clash, since the same Catholic Monarchs who claimed to protect their new governed established official measures that unceremoniously undermined those same rights. And not precisely as a conjunctural response to episodes of insurrection, civil disobedience and the like: in the case of Gran Canaria, reasons as bizarre as the fact that the number of Canarian families residing on the island exceeded that of European ones were put forward. This is demonstrated by two provisions, transcribed and published in 1969 by Professor Antonio Rumeu de Armas.

In the first of these letters, In the first of these letters, issued on September 27, 1491, the Catholic Monarchs decided in favor of a request made to them by the council authorities of Gran Canaria, concerned about the number of native families who had returned to the island eight years later after their expulsion –that is, at the end of the War of Canaria in 1483– had increased to about 150 when Don Fernando Guadarteme or Guanarteme, formerly the island chieftain, had been allowed to designate a maximum of 40 relatives, heads of family, so that they could remain in their country in recognition of their collaboration with the invaders, and it can be just guessed that the rest of the autochthonous population must have suffered deportation at that time[1]All the following translations by PROYECTO TARHA.:

[…] for doing good and favour to Don Fernando de Guadalterme [sic], a Canarian, we gave him the right to live on said island with forty of his relatives who had been in the conquest of said island, and since then to now eight years ago […] the said island has grown and been populated with many other Canarians on which he says that there are now about one hundred and fifty, a bit more or less […]

Increase of the Canarian population alerted the settlers who seeing themselves being outnumbered feared the possibility of a reconquest:

[…] it is feared that having multiplied themselves this way according to the scarce population of Christians on said island one day they would uprise with said island against them […]

The plea to the monarchs was effective despite the fact that it contravened the documentary commitments that equated the rights of the indigenes to those of the other subjects of the Castilian crown:

[…] should some Canarians more than and beyond the said forty that we ordered to live on the said island have gone to live on it make them leave the said island and come to any part of these our kingdoms or outside of them wherever they want.

But some of the deportees were reluctant to obey the royal mandate, so on December 23 the monarchs ordered the councils of Jerez de la Frontera, Cádiz, Puerto de Santa María, Rota, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Huelva, Palos and Moguer to sentence to death the Canarian families who ignored the decree and confiscate the ships and properties owned by those who provided them with passage back to their country –see our transcription–:

[…] we had ordered and defended that some of the Canarians from the island of Gran Canaria stayed not on the said island of Gran Canaria and that they be thrown out of it, and that if some of the said Canarians went to said island without our permission and order they must die because of that […] and now we have been told that the said Canarians of the said island with their wives and children want to go to the said island […] therefore we command and defend […] that you do not consent nor give rise for […] them to board or enter or being taken […] and punish such persons who take and cross them over to the said island to have lost and lose the ships and light galleys and caravels and boats in which they crossed them over, and […] to the said Canarians and their wives and children that neither they nor any of them dare to go to the said island without our license and mandate and special letter for it, under sentence of death […]

This is just one of the evidences provided by public documentation on the existence, in practice and despite the commitments assumed by the Crown, of a patent asymmetry of rights between the new European population and the Canarians, an imbalance that would manifest itself in more than one occasion, even among members of the indigenous aristocracy supposedly favored by their collaborationist position during the Spanish conquest. For instance, on July 5, 1514, some personalities belonging to the island elite would come to request Queen Juana I and her father, Fernando II the Catholic, to relieve them of serving militarily away from the Canary Islands in consideration of the services provided in the campaigns of Gran Canaria, Tenerife and La Palma.

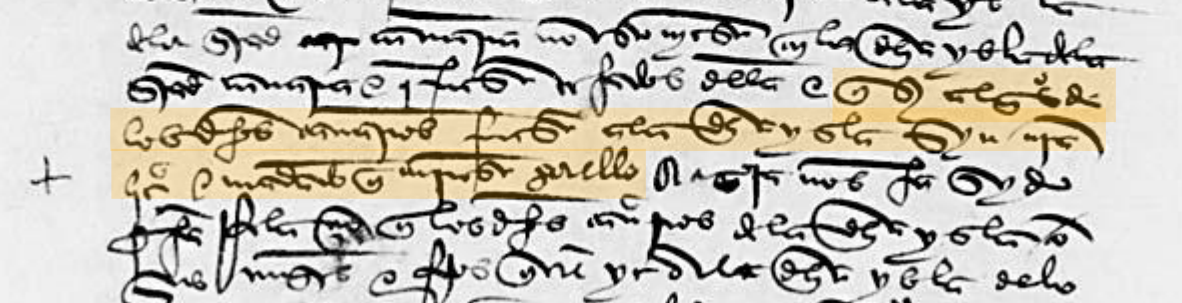

“[…] should some of / said Canarians went to said island without our / licence and mandate make them die because of that […]” (source: Archivo General de Simancas, catalogue number RGS,LEG,149112,168).

It is curious that the Grandcanarian petitioners, in order to assert their prerogatives, commissioned their representatives to make know that they were not like the natives of the other islands lastly subjected, namely Guanches, Benahoarites and Gomerans; rather, they had to emphasize in their defense that they, even bearing Canarian names, spoke like Castilians and were considered as such[2]RUMEU DE ARMAS (1969), p. 454.:

[…] to their Highnesses make a relation of the manner and quality of our people and way of living and manners, which is very good to God Our Lord […] being therefore firm in the Holy Catholic faith as good Catholic Christians are and should live in manners and conversation; so that it is not to understand that by bearing Canarian names does our people be diminished for they have nothing to do with the natives of the other islands, namely Guanches and Palmeses or Gomerans, having as we do many advantages over them in everything and we do speak and are considered as Castilians.

Dazzled for decades by the technology and culture of the Europeans, when not directly or indirectly coerced by them, the ancient Canarians, particularly the members of the social apex, were to marginalize their own traditional heritage in search of a prestige and recognition that never came to materialize beyond the crumbs, always collateral, that every process of conquest drops in its path for cheap content and long containment of the subject peoples.

Antonio M. López Alonso