An idealized statue of Doramas by Grandcanarian sculptor Abraham Cárdenes (1907-1971) (source: MILLARES TORRES, A. et al. (1977 [1893]), Historia General de las Islas Canarias, vol. II, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: EDIRCA, p. 178).

In our post devoted to Benahoarite chieftain Tanausu we pointed the importance of the ancient Canarian heroes in the building of the Archipelago’s folklore.

This value reaches a paradigmatic height in the case of Grandcanarian warrior Doramas by adding to the classic personal attributes of courage, abnegation and self-sacrifice, typical of a heroic model, that of the subject of humble origins determined to build his own destiny, who strives to ascend with his only effort along the social pyramid to which he belongs, while simultaneously facing the obstacles placed both by the status quo –an islander oligarchy determined to perpetuate itself in power through the instrument of lineage– and by forces other than internal social contradictions –European invaders–.

However, following the opinion of some authors, let us note that this framing of the character within the topic of humility of origin it is more a literary license than a verified fact, because although all the ancient sources biographying Doramas –superficially– confirm without doubts his belonging to the class of the “sheared” -the lowest in the ancient society of Gran Canaria, grouping butchers and “shrouders”altogether in the lowest sublevels- this did not necessarily rule out a prior condition of privilege, potentially granted through parental filiation, since the nobles or the guadarteme –higher chieftain– himself could engender noble offspring even in women of the common stratum, a progeny that, in order to raise their starting social position, had to submit, once they reached adulthood, to a public trial of nobility that confirmed in the individual the non-commission of unworthy acts or behaviors, or the performance of tasks considered inappropriate for the upper strata. And of course, after the effective acquisition of it, the loss of noble status for these same reasons is something that falls under its own weight. In any case, whether Doramas was a “sheared” from birth and without remission because of his parents, or right a nobleman, or a contender to be a nobleman, his first “job” as a cattle thief, attested by some narrative sources, annulled all possibility of acquiring or maintain that state.

Two deaths for one hero

We will not make a biographical sketch of Doramas here, a task that has already been undertaken on a number of occasions by other authors, both from a historiographical perspective, such as Professor Juan Álvarez Delgado in his classic article Doramas: su verdadera historia (Doramas: His true story) –although some of his premises and conclusions are quite questionable–, as from a more literary approach, in the case of historian Agustín Millares Torres, with the work Doramas included in his «Biografías de canarios célebres» (Biographies of Some Famous Canarians). On the other hand, it is our intention to give some notes on the episode that definitively consecrated this Grandcanarian warrior as a legendary hero, which is that of his epic death in combat against Governor Pedro de Vera and his men, who had left on an punishment raid to find and hunt down who at that time was considered to be the main leader of the islander resistance against the Castilian invasion forces, on a date imprecisely located between the end of July 1480 -a few days after Vera’s first arrival in Gran Canaria– and some St. Andrew’s day –November 30– of that year or of 1481[1]This is the day in which historian Tomás Marín de Cubas dates this skirmish in book II and chapter VII of his History of the seven Ysles of Canaria (1694)..

For Historiography, Doramas’ life ends in two different ways: the one narrated by baroque historian Brother Juan de Abreu Galindo and the one attested by the other ancient accounts, which is the one followed by historians after Abreu Galindo –with the exception of Brother José de Sosa who opted for a story similar to Abreu Galindo’s, but shorter–, and that do not present much variation among them with a single and notable exception: the almost cinematographic but not necessarily dramatized version by Tomás Marín de Cubas.

The first chronicles

The chronicles named Ovetensis[2]MORALES PADRÓN (1978), [ch. XV], p. 145 and Lacunensis[3]MORALES PADRÓN (1978), [ch. XVI], pp. 212-213 closely textually followed by the accounts by Francisco López de Ulloa[4]MORALES PADRÓN (1978), [ch. XV], pp. 296-297 and Pedro Gómez Escudero[5]MORALES PADRÓN (1978), [ch. XI], pp. 407-408 offer one vision of last clash of Doramas matching what is expectable for a late-medieval combat adding the value of locating and relating the skirmish to toponymy existing at present. For instance the Ovetensis claims on this matter[6]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.:

At last Governor Vera with all his people that he had and those who had newly come agreed to make a great cavalcade such in a purposely way with which to scare and intimidate the Canarians who were so arrogant, as he did, and it happened well because on the first day he hit the spot where the Canarians were together and he was to go on the way to Arucas to put them in fear that, as it is customary in military art, he wanted to represent the battle to them from a hill and ridge in front of where they were, that was a sight place, all the people going at length and the horses taking a long way so that the people seemed more than doubled. At last, going down to the valley they call Tenoya, he went up the high hills that go towards Arucas and, arriving in sight of the Canarians, with great fury he charged and they charged at them, both the people on horseback and on foot who received them with no less courage and spirit and defended themselves from our men and offended them, and Doramas marked many of them with his toasted-wooden sword, very heavy and large that later a very strong man of ours could not wield it with both his arms and he wield it more freely with one hand and made a very large field around himself because everyone guarded against his strong blows that would cut the hamstrings of any horse he struck, and cut an arm or a leg as if it was made of iron, and even worse because its blows and wounds had no cure, moreover the spears that the said and the others threw any armed man they hit the mark would die and also the stones as if they were thrown with large ballistae of the old times.

The Castilians, being aware of the Grandcanarian warrior’s charisma and his dangerousness as an opponent chose to isolate him from his companions, surround and attack him as a group. A common tactic in medieval field combat, far from the chivalry that literature often invokes to adorn these violent episodes:

In the end, ours would had a hard time if it were not for God that the great Doramas would die because Governor Vera and other knights, out of desperation, leveled their lances against him and attacked at the same time and hit him in the side, which if they had not more than one to attack him, he was so swift that he knew how to escape the blows, but since they were so many he could not, and when the other Canarians saw him fallen, it was not necessary anything else for everyone to turn their backs to save themselves.

Victorious Vera could not help but display his adversary’s head as a trophy and warning:

Finally, being some of them dead and others wounded and others captives, soon after the death of Doramas the battle ended and the fort they had made was destroyed, and Governor Vera ordered Doramas’ head to be cut off and brought on a spear and put it in the middle of the plaza San Antón, which was the main of the camp where the city is now which was then called Gueniguada.

A present sight of the likely scene of the so-called Battle of Arucas where Doramas died at the hands of Governor Pedro de Vera and his hosts. In the foreground Tenoya neighborhood on the edge of the homonymous ravine (valley). On the other side, Lomo de Arucas (Arucas Hill). At half-distance to the right, the town and mountain of Arucas (source: Google Earth).

The chivalrous version: Abreu Galindo

Traditionally, the texts above are believed to derive from an original text attributed to Alonso Jáimez de Sotomayor, the main ensign of the conquest of Gran Canaria, for which reason they are essentially supposed to be worthy of a certain amount of credibility. This contrasts, however, with the version provided by Abreu Galindo, for whom the dogfight never took place thanks to Doramas’ initiative to propose to his opponents, and they accept, to replace the field confrontation with the celebration of a duel between him and some chosen one of the Castilians, in the chivalrous manner. After killing the first volunteer Doramas confronts Vera in person, and the latter mortally wounds him and thus the Canarian gave up the fight[7]ABREU GALINDO (1848 [1632]), [book II, ch. XVIII], pp. 133-134. This translation by PROYECTO TARHA:

The brave Doramas, when he saw that the Christians were approaching him sent to say if there was a knight among them who wanted to prove himself against him. He was answered yes. Pedro de Vera wanted to take the step but his people did not consent to it, saying that if, God forbid, some misfortune happened to him they would all be left to stand without their captain and government. Out of those on horseback came a nobleman named Juan de Hozes who said he wanted to prove himself against the Canarian whom he did not know, and he went to where Doramas was who seeing him coming to himself threw a susmago at him, a sort of dart, which passed through the buckler and mail that he wore and his chest and he fell dead. Pedro de Vera greatly regretted the death of this nobleman and began to go out towards him much quietly. Doramas knowing that the one who was coming to him was the captain of the Christians with his pride and arrogance of the luck he had achieved understood that the same would happen to him with Pedro de Vera, and while Doramas was close enough he threw a susmago at him which he countered with the buckler and deviated past him and tilting the body the susmago passed by not hurting him and he tried to get closer just to make Doramas throw another at him and Pedro de Vera crouched his body as much as he could and the susmago passed over and wounding the horse with his spurs he charged at Doramas and hit him with the spear wounding him badly on one side; he was going to hit him again and Doramas made a sign of surrender. The Canarians, when they saw Doramas fallen, charged at the Christians with great fury, impetus and rage, where there was a well-fought fight because the strength and prime of the Canarians were there and many of them died there and the rest left retracting uphill.

To finish off the implausibility of his gallant story Abreu Galindo makes his dying Doramas ask for baptismal water omitting any mention of the severed head of the fallen man:

Returning to where Doramas is, fallen and badly wounded, he said he wanted to be a Christian and squeezing the wound from which a lot of blood had flowed they began to come to the camp and they climbed the Slope of Arucas and then he had great nausea and anguish to death and he asked to be baptized, and bringing water in a helmet they baptized him, his godfather being Pedro de Vera who named him Pedro. Having just been baptized, with signs of a Christian, he expired giving his soul to God. The Christians and some Canarians who had come with him who had not wanted to leave him buried him on top of the mountains and made a fence for him in the same place where he is buried and put a cross that is there today.

Leaving aside the improbability that Pedro de Vera agreed to face a character whom he would undoubtedly consider inferior, unworthy of the prerogatives of noblemen, in a duel of equals, we must point out the fact that, of course, this is not the first story that the supposed Franciscan adorns with unusually idealized details, of which we can find other samples in his also not very credible version of the death of Fernán Peraza the Younger, or in the result of the negotiations between Diogo da Silva and the Herrera-Peraza family to recover the Tower of Gando. It is true that we are not in a position either, out of hand, to blame Abreu Galindo for inventing these models, since they could well come from his informants, perhaps interested in inducing a particularly biased view of the facts.

The most epic version: Marín de Cubas

El hecho de que el doctor Tomás Marín de Cubas fuese, a tenor de sus escritos, un rendido admirador de Abreu Galindo y el primer integrador extenso y explícito de la obra historiográfica de este en su propia producción, no impide que mirase los datos ofrecidos por el fraile andaluz con ojo ciertamente crítico, y prueba de ello es su renuncia a hacer uso de los relatos del franciscano sobre las muertes de Fernán Peraza y Doramas, reemplazándolos por unas versiones épicas, y por qué no decirlo, casi cinematográficas de ambos sucesos, que hoy en día siguen causando emoción y admiración por su descarnado realismo. Sin entrar en su análisis, dejemos que sea el propio relato del combate final del guerrero grancanario el que hable de su excepcionalidad[8]MARÍN DE CUBAS (1986 [1694]), [book II, ch. VII], pp. 191-192. This translation by PROYECTO TARHA:

The Spaniards being quite offended because of the heavy taunts of the Canarians and their audacity, Pedro de Vera trying to punish them, by agreement of everybody he left on St. Andrew’s day, Wednesday, leaving enough garrison in the camp, with 50 horse lances and 200 pawns in search of the enemy on the way to the mountains towards the valley of Tenoia, or Tenoja, before Arucas; they led the horses apart from each other taking a lot of field. They were led by General Pedro de Vera. He carried the two-pointed white banner with Castile and Leon as a sign of peace as Ensign Jáimez always did, all of them firstly determined as Christians and made the exhortation to do their duty according to good law; having walked one league they saw some armed Canarians who were gathering and half a league ahead many were seen on the cliffs walled up or stuck in stone corrals as a fortress waiting for them to reach them: we halted and suddenly many Canarians came up the valley armed with two-handed wooden swords, very fast to the horses, this was the crew of the famous Doramas who came from the sea where they had bathed until the news of our arrival made them come; first the crossbowmen fired some shots at them and others with fire, but not allowing more, it was forceful to spear them which did them a lot of damage. Some of great repute, both Christian and Gentile, fought and the most famous was the havoc that Doramas wreaked. He waved his sword with one hand so that no man could enter him, others threw a dart that could pierce an armed man and a horse, and fire shots hurt them from afar, and Doramas said “Come to me six, twelve, and twenty and do not shoot from afar» and he was always yelling and saying opprobriums of femented dogs, traitors, in his language; he made many movements with his body, now withdrawn, now uncovered, using his blows to save himself. Seeing Pedro de Vera he was committing greater damage he recognized him and went after because the first to attack him was Juan de Flores, who jabbing the horse hard went so far that Doramas, breaking his lance, also broke his head with a backhand. Pedro López, a foot soldier, followed him and he also took the sword from his hand; knocking down others on horseback two others entered with Pedro de Vera to surround him like a bull, the first on the left side, in such a way Doramas did not judge, was Diego de Hozes, a Cordovan, who wounded him on the right back and took in return a backhand that broke his left leg; Pedro de Vera entered then, giving him a second spear hit through his chest and then they shot him in the arm; Doramas said to the former “You shall not go away praising yourself”; to Pedro de Vera, “It is not you who has killed me but this traitor from behind” and finally to quit shooting him from afar like treacherous dogs, that he would drink everyone’s blood and then he began to get stunned, bleeding to death, asking for water because of the death thirst. They judged that he wanted to be baptized and it was just for drinking. They brought some on horseback almost 80 paces from there in a German hat filled with water; they put it in an iron helmet, he drank it and it came out clear from his wounds and then he died. His head was cut off and brought before by a captivated Canarian on a thick pole belonging to his comrades who let themselves to be caught to not abandon him; the other Canarians fled when they saw him now wounded: the sun was shining hot, it was ten o’clock, the walls were knocked down and after resting a little Pedro de Vera went his way back to the camp. His head spent many days in San Antón plaza as a lesson to the daring; the wooden sword that he wielded with one hand, as if it were just a cane, a Spaniard could not swing it well with his two hands. The strength he had gave admiration to everyone. He was not very tall in body but he was thick, broad-shouldered with a large head, round face, small nose and very wide nostrils; middle-aged, well-distributed limbs.

Pedro López: A «new» chronicler?

So ends this unforgettable episode in the History of the Seven Isles of Canaria which Marín de Cubas completed in 1694, and which to this day still lacks a complete edition. Of course, the question is unavoidable: where did Marín de Cubas get this exquisitely detailed account of the event which combines the use of the third-person narrative with occasional first-person interventions? Because although it cannot be ruled out that it could be a fictitious recreation elaborated by the, on the other hand, very well documented Canarian historian the text scheme has a complexity that is difficult to justify due to mere fantasy in the scope of a historiographical opus that is already quite dense.

In our opinion the key to this enigma may have to be sought in the name of the “soldier” whom Doramas disarmed during his last fight and who, without anything in the story that makes us suppose otherwise, is still alive after the skirmish: Pedro López.

In the volume of 1694 we will not find any mention of this name again. However, we will achieve it in the very interesting draft of this work, written in 1687, which we recently had the pleasure of publishing in its entirety as a critical edition: Conquest of the Seven Ysles of Canaria. Specifically, in chapter XIV of book I Marín de Cubas provides us with the following text holding so much substance in its brevity that we almost feel mad at[9]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.:

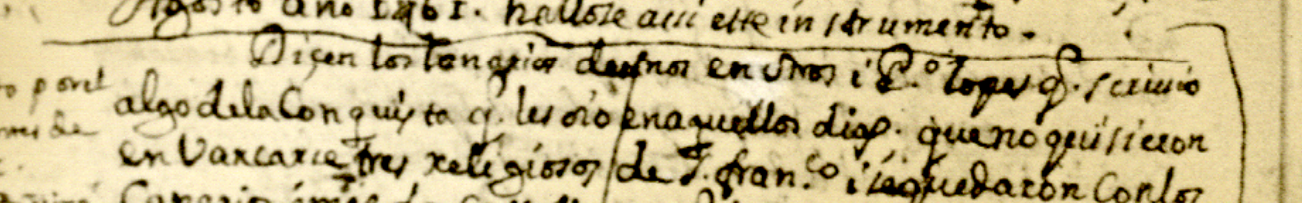

Canarians do tell each other and Pedro López who wrote something about the conquest who heard them in those days […]

“Canarians do tell each other and Pedro López who wrote something about the conquest who heard them in those days […]” (source: Biblioteca Insular de Gran Canaria, Fondo Miguel Santiago, catalogue number MS A57/03(2), f. 34v).

Are both names the same character indeed? It is a pity that the text that follows this acknowledgment – the story of some Franciscan missionaries– does not shed more light on this “new” chronicler, of whose work we still have no other trace than the one that Marín de Cubas wanted to leave for us in his writing.

Antonio M. López Alonso

References

- Abreu Galindo, Fr. J. de (1848 [1632]). Historia de la conquista de las siete islas de Gran Canaria. Escrita por el Reverendo Padre Fray Juan de Abreu Galindo del Orden del Patriarca San Francisco, hijo de la provincia de Andalucía. Año de 1632. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Imprenta, Lithografía y Librería Isleña.

- Álvarez Delgado, J. (1970). “Doramas: su verdadera historia”, Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos, vol. 1, n. 16, pp. 395-414. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Cabildo de Gran Canaria.

- Marín de Cubas, T. (1986 [1694]). Historia de las siete islas de Canaria. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Real Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País de Gran Canaria.

- Marín de Cubas, T. (2021 [1687]). Conquista de las Siete Yslas de Canaria (1687) : Tomás Marín de Cubas : Edición crítica de Antonio M. López Alonso. La Orotava – Santa Cruz de Tenerife: LeCanarien ediciones.

- Morales Padrón, F. (1978). Canarias: Crónicas de su conquista. Sevilla: Excmo. Ayuntamiento de Las Palmas – El Museo Canario.