A recreation of an ancient Gomeran woman according to Leonardo Torriani circa 1590 (source: Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra, catalogue number Ms. 314, f. 81r.)

To commemorate 20 November 1488, the day La Gomera allegedly uprose against Fernán Peraza the Younger, the Castilian lord of the island, we are going to continue our previous couple of posts on this important historical milestone with an unpublished testimony that sheds more light on the events and propose a new hypothesis based on these data.

This is the statement made in La Gomera on 27 February 1590 by Pedro Hernández Muñoz, notary of the ecclesiastical court, in an interrogation of witnesses in the context of the complaint filed by Hernán Sánchez Moreno, one of the aldermen of the council of La Gomera, against Martín Manrique, notary of the Holy Office of the Inquisition and a municipal alderman also. With the questions put forward in his defence, the defendant sought to undermine the credibility of his plaintiff by invoking the latter’s obscure family background and contrasting it with the brilliance of his own lineage, among other tricks.

We should first point out that Canarian historiography is already familiar with part of Pedro Hernández Muñoz’s statement thanks to a fragment, no less important than the one we are about to mention, quoted in 1967 by Professor Alejandro Cioranescu to support a novel hypothesis that he would develop in 1995: to incarnate the true identity of the baroque historian fray Juan de Abreu Galindo in fray Juan de San Francisco, provincial of the Franciscan order in the Canary Islands around 1560-1563[1]This hypothesis would be adopted in 2004 by Professor Antonio Rumeu de Armas without mentioning Cioranescu’s precedent..

We now offer our reading of this fragment, included in the file preserved in the Fondo General Canario del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición, in the archive of El Museo Canario, under the modern catalogue number ES 35001 AMC/INQ-052. 016 (folio 29), noting that both Professor Cioranescu and, years later, the researcher José Antonio Cebrián Latasa made a mistake in the name of the declarant, which they transcribed as Juan Fernández Núñez, and not Pedro Hernández Muñoz, as well as making a mistake also in the year of the testimony, which they indicate respectively as 1581 and 1585[2]VIERA Y CLAVIJO (1967 [1772-1783]), pp. 483-484, and CEBRIÁN LATASA (2007), p. 116. We modernised the language and punctuation:

Furthermore [the witness Pedro Hernández Muñoz] said that, going through his memory, while he was on the island of Canaria talking to Brother Juan de San Francisco, his brother provincial who at that time was in these islands, he showed him and gave him to read the order that was taken about conquering these islands, written in handwriting, composed by Alonso Jáimez Sotomayor who was married to a daughter of Esteban Zambrana, a cousin[?][3]The final vowel is somewhat blurred, so we cannot rule out the possibility that it is “father”, as Cioranescu and Cebrián Latasa read it, although we do not know whether the latter offers his own reading or simply follows the Romanian historian. Nevertheless, we believe that the expression “father of his father of this witness”, if true, seems a somewhat convoluted clarification that the witness could have resolved much more simply with a “grandfather (paternal) of this witness”, a “married to aunt of this witness” or a “married to a sister of the father of this witness”, so we opt for the kinship of cousins, while waiting for some genealogical analysis that may confirm or reject it on the merits. of the father of this witness, who was one of the principal conquerors of the said island […]

Killing Fernán Peraza

The rest -as we say, unpublished- of Hernández Muñoz’s statement begins by echoing the very brief reconstruction that the old chronicle made of the uprising, simplifying the cruel reprisal that Pedro de Vera, governor of Gran Canaria, would unleash on the people of La Gomera:

[…] and in one chapter he told how the Gomerans killed Hernán Peraza, lord of these islands of La Gomera and Hierro, and how Pedro de Vera, captain appointed by the Catholic Monarchs, came to this island, because he knew of the death of the said Hernán Peraza and was called by Doña Beatriz de Bobadilla, his wife, and he came with a large number of people and did great reprisals against the killers and those who gave them favour to kill him […]

As to the reasons for the uprising, the witness is clear about the causes:

[…] that certain Gomerans were implicated in it saying that [Fernán Peraza] was going around with their wives and daughters […]

But as for how Fernán Peraza’s death came about, the declarant offers new data adding nuance to what is stated in the narrative sources:

[…] and some of the elderly Gomerans advised them not to kill him but to seize him and take him prisoner to Spain and hand him over to the Catholic Monarchs, that they would do justice, and that they were thus diverted from doing so, and that with this advice the said Gomerans returned to their homes […]

And then nothing would have happened had it not been for the fact that on the way back the rebels met someone who had a special interest in making the despotic Castilian lord of the island disappear forever:

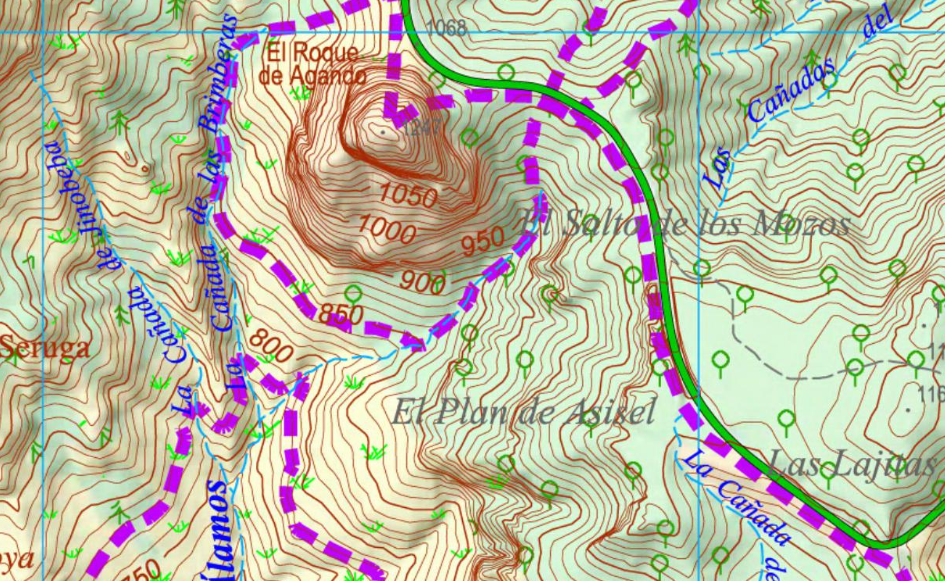

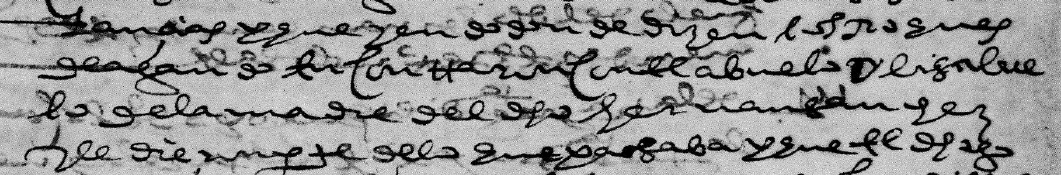

[…] and that going where they say Agando Rocks [they] met the grandfather [or] great-grandfather of the mother of the said Hernán Sánchez and they told him what was happening, and that the said Gomeran, who was one of the principal chiefs who were planning on killing the said Hernán Peraza made them [return] to execute their [broken] so with his advice they turned and [broken] that the said Hernán Peraza was in a cave with certain women of the Gomerans [broken] they went in and killed him, and in that place [a] cross was put on a rock which was called the Cross of Hernán Peraza, and so the killers and participants were pronounced traitors, and this is what he saw and knows in this case, and he has heard the same after he entered this island from elderly people and it is the truth because of the oath that he himself swore […]

This is therefore the first known testimony linking the magnicide of Fernán Peraza to a particular lineage: the maternal family of the alderman Hernán Sánchez Moreno, who ironically, according to the fourth question of the interrogation, had been appointed to the post by a grandson of the victim: Don Diego de Ayala, 2nd Count of La Gomera.

«[…] and that going where they say Agando Rocks [they] met the grandfather [or] great-grandfather of the mother of the said Hernán Sánchez and they told him what was happening […]» (source: Archive of El Museo Canario, catalogue code ES 35001 AMC/INQ-052.016, f. 29r).

Mencía «Bella»

Martín Manrique, the defendant, knew very well what he was doing when he presented the background of the Bello family, the maternal line of Sánchez Moreno, as proof that the complainant’s word and person were not credible, being “lowly people” who had once owned slaves, cattle and land, but who had become poor over time, with several of their members involved in crimes and ominous events.

Mencía Bello, daughter of Álvaro Bello, often referred to as Mencía “Bella”, the complainant’s mother, a baker and vintner, and one of her daughters, Úrsula Sánchez, were prosecuted by the Inquisition of the Canary Islands for insulting agents of the Holy Office[4]Manuscript ES 35001 AMC-INQ-107.004.; Álvaro Bello, Mencía’s brother, after returning from a sentence of exile in the Yndias de Portugal -India-, had been dragged, hanged and quartered for killing the governor Gonzalo de Amaya[5]ff. 23r, 32v.; Francisco Bello, another brother, was also prosecuted by the Holy Office for publicly declaring that he did not believe in God[6]Manuscript ES 35001 AMC-INQ-108.005.; and Mencía herself called a third brother, Esteban Bello, an “old thief”[7]f. 32v..

As if these antecedents were not sufficiently discrediting, Manrique also brought up the case of Hernán Méndez, Portuguese or Castilian, grandfather or great-grandfather of Sánchez Moreno, married to a woman of the Bello branch, who was hanged together with one of his daughters for incest, several witnesses affirming that another “incestuous” daughter, fleeing from her father, had thrown herself from a rock near the rock of Agando, which from then on was called Hernán Méndez’s Rock -toponym now lost-[8]ff. 23r, 32r.. But the truth is that this other daughter, or maybe a third one, called Juana Méndez, escaped from the gallows by marrying a Galician blacksmith, Pedro Yanes, alias Pedrianes, at his proposal to save her from death, and at the cost of being later accused of bigamy by the Holy Office, as he was already married to a Portuguese woman[9]Manuscript ES 35001 AMC-INQ-094.003..

The Rock of Agando and, to the right, the slopes of Plan de Asisel or Aseysele. (source: dronepicr / Wikimedia Commons).

In the footsteps of Pedro Hautacuperche

We ventured earlier that the grandfather or great-grandfather of Mencía “Bella”, the individual who finally instigated the killing of Fernán Peraza the Younger by disregarding the opinion of the elderly Gomeran chiefs to hand over the Lord of La Gomera to the judgement of the Castilian crown, must have had a special interest in eliminating the despot, probably a more intimate, personal one.

From Brother Juan de Abreu Galindo, followed by physician Tomás Marín de Cubas, we already know that it was the shepherd Pedro Hautacuperche who led the group of rebels who went after Peraza, and who personally dealt him the mortal blow. From the first author we also know that Hautacuperche had his cattle in Aseysele, called in modern cartography the Plan de Asisel, just in front of the rock of Agando -let us remember that the rebels, retreating to their homes, met the ancestor of Mencía “Bella” in the “Agando Rocks”-, which makes the question unavoidable: was Pedro Hautacuperche the grandfather or great-grandfather of Mencía “Bella”? Or was he just one of those instigated by the latter to retrace his steps and finish off Peraza?

“Yballa was her surname”

In the light of the above information, those who have followed the text up to this point will have ceased to wonder why we insist on using quotation marks around Mencía Bello’s alternative surname -Bella-, as they will no doubt have noticed the striking similarity between this and the famous name of Fernán Peraza’s lover from Gomera, who witnessed the assassination: Yballa or, more recently, Iballa.

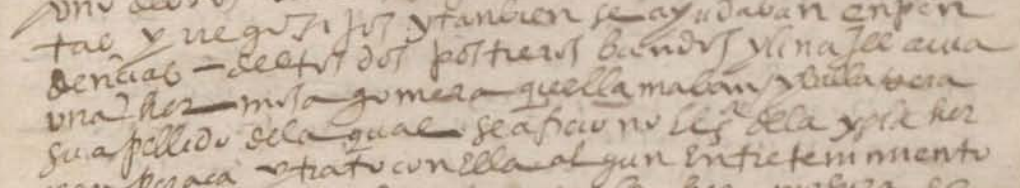

This would be no more than a coincidence were it not for the fact that the oldest source to attest to this name, the so-called Cronica Ovetensis[10]The account by Pedro Gómez Escudero also attests to the name of this Gomeran woman, but as only a copy made and very much interpolated by Marín de Cubas is known, it seems reasonable to doubt the greater antiquity of his testimony., in chapter XXIV, folio 133r, states that:

[…] there was a beautiful Gomeran woman they called | yballa | or was her surname […][11]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA. The strikeout does not appear in Professor Francisco Morales Padrón’s transcription.

«[…] there was a beautiful Gomeran woman they called | yballa | or was her surname […]» (source: Biblioteca de la Universidad de Oviedo, catalogue code M-164, f. 133r).

Given that of the so-called “Mother Chronicle”, credited to the major ensign of the conquest of Gran Canaria Alonso Jáimez de Sotomayor, we only have presumed copies dating from the 17th century, one of which is this Ovetensis, we may speculate that the original text may have been something similar to this:

[…] there was a beautiful Gomeran woman they called [this omitted by the copyist] and (y) B[e]ll[a/o] was her surname […]

Of course, as we pointed out in the first part of this series, we could still accept that with the term “surname” the chronicler meant to refer to a nickname, and then what is proposed here would be at least partially invalid. But if the existence of a relationship between the anthroponym Yballa and the patronymic Bello / Bella were true, it seems pertinent to us to raise at least two possibilities:

- That, as has been presumed until now, Yballa was originally an indigenous name or surname from which the surname Bello / Bella was derived, at least in La Gomera.

- Yballa may have been a corruption introduced by a copyist when entering the surname Bello / Bella, of Portuguese origin, which would explain the rarity of the presence of the “LL” group in an ancient Canarian name, of which there are few examples in the Islands’ anthroponymy.

Needless to say how surprising it would be to find documentary evidence of the second possibility, as this would demonstrate the existence of Portuguese surnames among the indigenous population before their definitive subjugation by Castilian arms in 1489 -remember the notable influence that Portugal had among the Gomeran factions, attested, among others, by Gomes Eanes de Zurara- or, even more interestingly, the existence of a Portuguese-Gomeran mestizo population at the time of the 1488 insurrection, who participated in it.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor José Barrios García for lending us his copy of the manuscript ES 35001 AMC/INQ-052.016 for our transcription of it, as well as for pointing out the bibliographical references to Professor Alejandro Cioranescu on Brother Juan de San Francisco.

Antonio M. López Alonso

References

- Abreu Galindo, F. J. de (1848 [1632]). Historia de la conquista de las siete islas de Gran Canaria. Escrita por el Reverendo Padre Fray Juan de Abreu Galindo del Orden del Patriarca San Francisco, hijo de la provincia de Andalucía. Año de 1632. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Imprenta, Lithografía y Librería Isleña.

- Cebrián Latasa, J. A. (2007). «Apuntes para un catálogo de autores que han tratado sobre la Historia de Canarias», Cartas Diferentes: revista canaria de patrimonio documental, n. 3, pp. 109-151.

- Cioranescu, A. (1995). «Fray Juan de Abreu Galindo y el señorío de Canarias». Estudios Canarios: Anuario del Instituto de Estudios Canarios. núm. 39. pp. 135-146.

- Marín de Cubas, T. (2021 [1687]). Conquista de las Siete Yslas de Canaria (1687) : Tomás Marín de Cubas : Edición crítica de Antonio M. López Alonso. La Orotava – Santa Cruz de Tenerife: LeCanarien ediciones.

- Morales Padrón, F. (1978). Canarias: Crónicas de su conquista. Sevilla: Excmo. Ayuntamiento de Las Palmas – El Museo Canario.

- Rumeu de Armas, A. (2004). «Fray Juan de Abreu Galindo, historiador de Canarias». Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos. n. 50. pp. 839-851.

- Viera y Clavijo, J. de (1967 [1772-1783]). Noticias de la Historia General de las Islas Canarias. Sexta edición. Publicada, con las variantes y correcciones del autor. Introducción y notas por Dr. Alejandro Cioranescu. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Goya Ediciones.