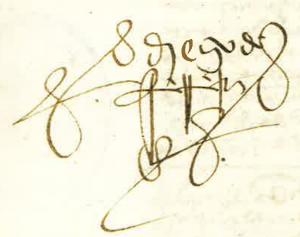

Diego García de Herrera's signature

Signature by Diego García de Herrera, consort Lord of the Isles of Canaria, in 1457 (source: Archivo Municipal de Burgos, catalogue number C3-3-16-27, fol. 5v.).

Studying public documentation is extremely useful when reconstructing historical events, since it provides us with an officially attested vision thereof. Unlike chronicles and histories, being these accounts written from the subjectivity of either an observer or, at most, a remote-in-time inquirer, public documents, being drafted by such a group of professionals in writing data down –scribes and notaries–, offer a direct testimony by those events’ main persons or at least by firsthand informants.

This is why in the course of our research we try to locate a larger quantity of public deeds, and although some of them are not directly related to the history of the Canary Islands, the possibility that these end up providing unknown, unnoticed or at least curious data always does exist. This is the case of the testament of Pedro García de Herrera, Marshal of Castile and father of the last consort Lord of the Isles of Canaria, Diego García de Herrera.