From Guise's side. From Ayose's side

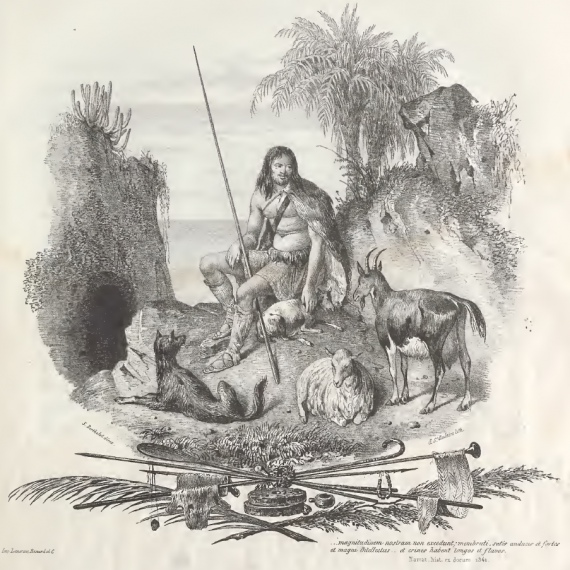

The idealised statues of Guise and Ayose, a work by Lanzarote-born sculptor Emiliano Hernández García, standing on the namesake viewpoint in the municipality of Betancuria in Fuerteventura (source: Luc. T / Wikimedia Commons).

In honor of my father’s family: my great-grandfather Matías Casanova “El Charco”, my grandmother, Susana Casanova Darias, and my great-aunt Manolita. From Vega de Tetir. “From Guise’s side.”

That Guise and Ayose were the names of the two maho chieftains who ruled Fuerteventura island at the time of the conquest by Jehan de Béthencourt and Gadifer de La Salle is something well known in Canarian popular culture. Such is so that the latter has been a relatively frequent anthroponym imposed among males born in the Canary Islands since the mid-1970s, a time when recognition and homage to precolonial cultural and historical roots began to be claimed with some force after being silenced for a long time.

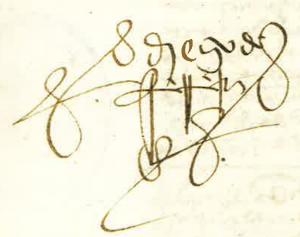

But a much less known fact is that both names survived the European conquest for four centuries without losing an iota of their everyday nature. And even more surprising is that they did not do it in the field of toponymy, a common refuge for forgotten words, but in a very unusual way: the administrative field.