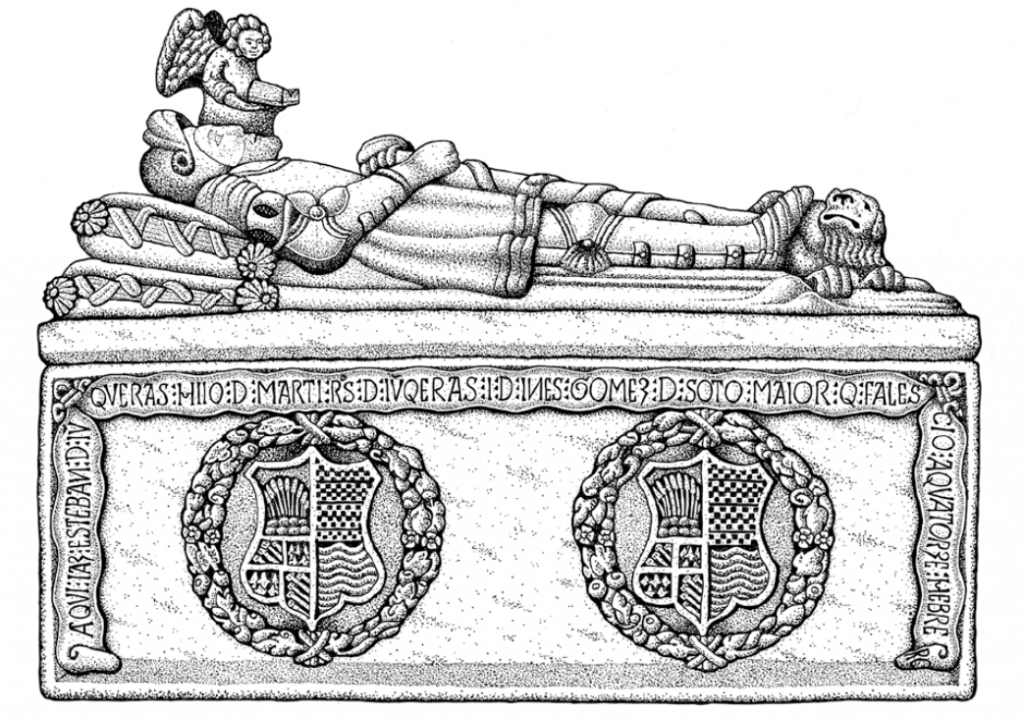

An idealized effigy of Captain Juan Rejón, military commander of the expedition to invade Gran Canaria ordered by the Catholic Monarchs, on a commemorative plaque located in Vegueta neighborhood, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, year 2018. (source: PROYECTO TARHA).

(This post has been extended with a fourth document, 11th December 2022)

By their nature, armed conflicts have always been a destination and a departure point at the same time. A departure point for those who are forced by violence to suffer the physical, cultural and emotional uprooting that fleeing from a war zone entails. A destination for those who see in the chaos of the conflict an opportunity to escape punishment, reprisals and persecution ordered by the established power or at the design of third parties, either for political or personal reasons, or because the fugitive actually exercised criminal violence against people or assets. In the latter case, war dresses the offender with a cloak of impunity that allows him to continue committing, this time with no other restriction than his own will, those or other crimes and felonies.

An especially profitable case of twinning between delinquency and warmongering is the employ of convicts by political power as war troops in order to fulfill its own interests, freeing those been governed from the risk posed by the presence of the criminal and on the other hand channeling towards the war effort at zero cost the latent aggressiveness in the person or alternatively his will to survive a conflict that he may judge as alien to his interests.

On this matter, three out of the four public documents whose transcriptions we are presenting here are not unknown ones. In fact they were listed in 1981 by Professor Eduardo Aznar Vallejo, one of them was partially copied earlier by Professor Antonio Rumeu de Armas and at least two of them have subsequently been the subject of discreet publications, although one of them is incomplete. We now intend to make them known in their entirety along with a fourth and to offer at the same time a broader perspective on their context.

(more…)

Más / More...