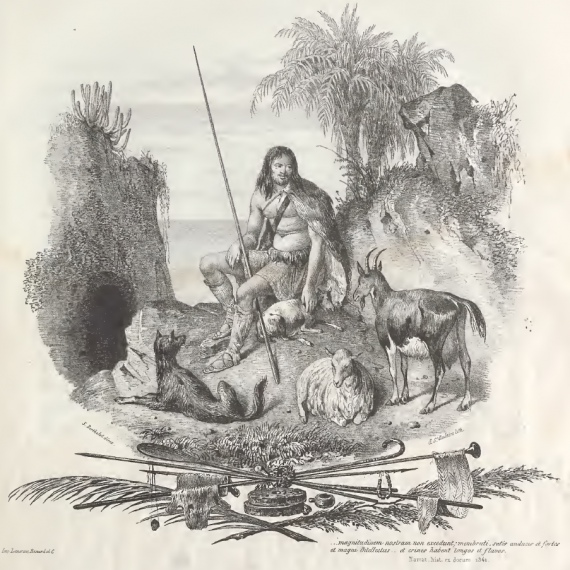

An idealization of a Canarian indigene according to lithographer A. de Saint-Aulaire, created to illustrate the first volume of the Histoire Naturelle des Iles Canaries, published in 1842 by botanist Philip Barker-Webb and ethnologist Sabin Berthelot (source: Archive.org).

The ancient history of the Canary Islands and, especially as best documented, the period that comprises the European conquest of the Archipelago have had little treatment in both historical novel genre as in cinematography, and almost invariably by the hand of either local authors or foreigners who have maintained some kind of relationship with the Islands, whether residential, sentimental or family.

It is relatively easy to guess the reasons for this lack beyond general ignorance. On the one hand, the greater prestige granted to other diachronically coincident events: the last stages of the War of Granada, Columbus’ arrival to America and the subsequent invasion campaigns of the discovered territories. On the other hand, it is clear that the conquest of the Canary Islands has rarely been perceived by the public authorities as an easy-to-manage historical process, especially regarding its integration in the educational system of the Islands, due to the evident political and sociocultural payload that entails.

One consequence is that, unlike the relative normality that presides over the debates and dissertations on the conquest of America and its insertion in the regulated education plans, the informative and formative contents that are imparted since primary education on the colonial phenomenon on the Canaries are, at best, anecdotal in terms of quantity and quality, being appreciated as decontextualized, when not directly disengaged, from contemporaneous historical processes whose pedagogy is considered relevant, such as the history, society and economy of the Hispanic Christian and Muslim kingdoms, the Reconquista, or the aforementioned Granada War. This shortage contrasts the rich and extensive scientific production devoted to this topic for more than a century, in which stand out, paradoxically, the signatures of renowned Americanists and medievalists such as professors Antonio Rumeu de Armas, Francisco Morales Padrón, Miguel Ángel Ladero Quesada or Eduardo Aznar Vallejo.

Recently we are experiencing a hopeful rise in the number of literary productions that stage the historical drama of the collision between the ancient Canarians and the European, but always from the no little commendable individual efforts in front of prevailing plots: see the cases of novels Guanches. Tiempos de guerra (Guanches. Wartimes) by Pepe Tejero from Tenerife, El último rey de Tenerife (The Last King of Tenerife) by Pedro L. Yúfera from Barcelona, or the Sangre (Blood) trilogy, by Carlos González Sosa from Gran Canaria.

In this struggle, audiovisual landscape is much more desert since that pseudohistorical 1954 Spanish-Italian co-production entitled Tirma presented the ancient Canarians, headed by Silvana Pampanini, in the guise of Amerindian riders with bows and arrows, but which at least has the merit of an epic staging with no offspring to date.

Currently, in productions of this genre, director Armando Ravelo stands out almost solo with his short films Ansite and Mah, as well as his theatrical productions Ancestro (Ancestor) and La Tribu de las 7 Islas (The Tribe of the 7 Islands), the latter aimed at the family audience and also released as a movie.

This time we want to review the brief treatment of the conquest of the Canary Islands from the perspective of two series of historical fiction, a genre that enjoyed a certain eminence in the 70s and 80s of the last century, in which we remember classics such as Marco Polo, Richelieu, Mazarin or I, Claudius, revitalized in the last dozen years thanks to productions like Rome, The Tudors and Vikings. Series that, counting on the appeal of casts to be charming enough for the general public together with a careful scenic setting, bring the ins and outs of certain chapters of History to the viewers, but with the usual narrative liberties that allow, on the one hand, to maintain the dramatic tension, almost always centered in the interpersonal relationships of the protagonists rather than in the events of which they are witness or part, and, on the other, not to excessively intellectualize the plots. The problem with these laxities, which are extendable to the literary field, is that they are not always acceptable from a minimally rigorous historiographic criterion and, yet seriously, they tend to induce in the public a distorted vision of the events that took place in a political, social, economic and cultural context completely alien to our time.

Generally, producers, directors and screenwriters try to cushion the impact of criticism in this regard by claiming the historical accuracy of their works by documenting the filming process of the series and invoking the authority of expert advisors who collaborate in the preparation of the scripts, then offering the result in the form of making-of documentaries to be telecast right after each chapter or as an addition to the editions in physical support of the main product, not forgetting the contents offered in web format.

As we said, let us review the cases of two TV series whose historical scenario coincides, at least in part, with that of the Castilian conquest of the Canary Islands: Isabel and Conquistadores Adventum.

The Isabel series and the Viceroyalty of the Canaries

Following the scenographic and aesthetic criteria proposed by The Tudors, although under an approach less focused to the physical ostentations of the protagonists, the Isabel series is a dramatized biography of Queen Isabella I of Castile, since her role as a marriageable princess immersed in the power struggle starred by her stepbrother, King Henry IV, the Castilian high nobility and Alphonse V of Portugal, until her death in the year 1504.

Although the struggle between Castile and Portugal for the occupation of the Canary Islands, a litigation the Catholic Monarchs inherited from their predecessors Henry III, John II and Henry IV until its resolution in 1479 by the signing of the Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo, is the key to explain the political, economic and strategic intricacies of the Atlantic expansion pursued by both crowns until reaching the American milestone, the series completely ignores this long-standing historical process and, particularly, everything related to the conquest of Gran Canaria, La Palma and Tenerife, being the latter a campaign that spanned eighteen years of those proposed in the narrative plot, from 1478 to 1496.

All in all, the Archipelago is mentioned only once in Isabel, and only to put an end to one of the subplots in the second season: the romance between Doña Beatriz de Bobadilla –renamed Beatriz de Osorio in the series to avoid making the audience confuse her with her own aunt of the same name, the Marchioness of Moya[1]That town in Cuenca, not the one on Gran Canaria., counselor and close friend of the Castilian Queen– and King Ferdinand the Catholic. In a brief scene, after arguing with the King –hour 1:05:17 in the video that follows–, the Queen tells the unruly lady her decision to marry her immediately to a nobleman of the highest rank: Hernán Peraza, Viceroy of the Canaries, who will have no chance but to accompany him to the Islands, disappearing definitively from the series.

The historical distortion is evident: the Canary Islands never were a viceroyalty, a form of government that was implanted for the first time fifty years later and only in the American colonies. The confusion is aggravated when we read in the epigraph that accompanies the scene in question that Peraza was Governor of the Canaries, a position that did not exist either, and he was accused of murder, a crime that none of the characters even mentioned. But, indeed, Peraza had gone to the Court to face the charge of having instigated the death of Captain Juan Rejón, the first military leader of the royal conquest of Gran Canaria. And, against all odds, the Sevillian aristocrat was acquitted of the homicide, on condition of marrying Bobadilla and serving in the War of Canaria leading a Gomeran detachment.

Being not sufficiently clear, the best approach to historical testimonies is provided by the presentation card of Beatriz de Osorio character, stating that:[2]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

During her stay in court, she was credited with an affair with King Ferdinand. That is why it is believed that Isabel made her marry Hernán Peraza, Lord of La Gomera, and sent her to the Fortunate Islands, thus distancing her from Castile and from her husband. From that marriage, two children were born: Guillén Peraza, first Count of La Gomera, and Inés de Herrera.

Hernán Peraza, her husband, died on La Gomera in 1488, murdered by his enemies, who hated him for his violent and dictatorial nature. It was then that Beatriz assumed the government of that island in the name of her daughter (?) and plotted a cruel revenge against the murderers.

Thus, further confusing the audience and visitors of the official page of the series, Fernán Peraza travels through a nonexistent viceroyalty and governorship to become only the Lord of La Gomera, which is really the title he held, as is that of Count of La Gomera, correctly assigned to his son Guillén, whom, by the way, we should not confuse with his great uncle, who was killed during the unsuccessful attempt to conquer La Palma between 1447-1448. After reducing the measure taken by Queen Isabel to the product of an attack of jealousy, although this time, at least, in line with ethnohistorical sources, historical events are again decontextualized and even undervalued, firstly, by charge the responsibility for the death of Fernán Peraza upon some indeterminate enemies and, secondly, to limit the response of Bobadilla to a cruel revenge against them.

Nothing is said about the fact that the intervention of the Herrera-Peraza family, in collaboration with Portugal and the ancient Grandcanarians, could have ruined the Castilian conquest of Gran Canaria and, therefore, not to fail the plan in extremis, the terms agreed in the Treaties of Alcáçovas-Toledo and Tordesillas would have been very different, leading, in all probability, to an American adventure radically different from the one we know.

Nor does it arise that, apart from other more-intimate interests, the monarch’s intention in sending her chambermaid into an enforced marriage and exile was likely to introduce a source of discord in Doña Inés Peraza’s small but diplomatically annoying queendom, rather than getting rid of one of the various lovers that King Ferdinand had, as it is known. Nothing about the death of Fernán Peraza being the beginning of a full-blown uprising of the indigenous population of La Gomera against the Castilian manor, and not the outcome of the aversion felt by some vague personal enemies. And nothing about the cruel revenge of Beatriz de Bobadilla being the unofficial realization of the reprisal ordered by the Crown to Captain Pedro de Vera, whose dramatic consequences include the mass execution of a large part of the Gomeran population and the surrender to the slavery of many of the survivors, action this last that the Catholic Monarchs had to amend through a long and complicated process that we have described in broad strokes in the previous post.

It is fair to point out that we are not the first to make a review of the scene in question, because Dr. Enrique Gomáriz Moraga wrote in 2013 a criticism about it, entitled Falsifying History: the case of Beatriz de Osorio, although devoted to assess the accuracy of the series itself, rather than that of the particular historical events.

The first of the colonies

(Improved section: we would like to acknowledge Ángel Amador for his convenient remarks on the foundation of San Marcial del Rubicón)

Conquistadores Adventum, unlike Isabel, departs from the merely aesthetic precepts to approach the documentary scheme, and it is in this aspect that the series stands out from other similar ones, even those produced in non-Spanish language. Thus, being the writers free of the soapy component that wears down other series of historical fiction, it is clear that they concentrated their narrative effort in contextualizing their characters in the social and cultural space of the time.

But, as is to be expected, this production also excludes the Canary Islands from their discourse about the individuals who carried out the ultramarine campaigns of conquest undertaken by the Crown of Castile, since the intention of the same is to offer, according to the synopsis, eight episodes full of data on the first 30 years of the discovery and conquest of America.

Consequently, under this premise, the series excludes the more than ninety years that the throne of the Trastámara invested in completely annexing the Archipelago to its domains and, therefore, the resounding precedents of Jehan de Béthencourt, Gadifer de la Salle, Fernán Peraza (grandfather and grandson), Diego García de Herrera, Juan Rejón, Pedro de Vera and Alonso Fernández de Lugo, among others, are silenced. It is even in accordance with this logic that in the first episode Christopher Columbus‘ arrival at the Canary Islands is omitted during his first trip, since it could hardly contribute anything valuable to the plot line.

What is discordant, from the pretended historical accuracy of the series, is the statement made, in the minute 44 of the first chapter, by the narrator of the plot, an anonymous member of the crew that accompanies Columbus on his first transoceanic trip, after the scene in which the Genoese captain decides to return to Castile after improvising the construction of the first Spanish settlement in America, known as Fuerte Natividad, with the remains of the Santa María flagship. In particular, the unknown adventurer sentences that he and his companions are the first settlers in the first of the colonies.

Since the intention of the writers is to narrate the first vicissitudes of the conquest of America, the meaning of the phrase can not escape to any person knowing the beginnings of the Modern Age in Castile. But as the production aims to reach an audience that mostly ignores certain historiographical details, we must conclude that this line of monologue goes beyond the limit of the merely ambiguous to falsify historical facts.

Because, of course, Fuerte Natividad was the first of the Castilian colonies in America. But the first overseas Atlantic colony of the Crown of Castile was San Marcial del Rubicón, on Lanzarote; as for even when the milestone of its foundation corresponds to the Norman-French expedition commanded by Jehan IV de Béthencourt and Gadifer de la Salle in 1402, the former’s homage to King Henry III as Lord of the Isles of Canaria and the final submission of the new lordship to Castilian law in 1422 (Laws of Niebla-Toledo and the Seven Partidas) point to the Hispanic kingdom as being a major promoter in the initiative. Plus, San Marcial del Rubicón was the first overseas Atlantic colony to receive the title of city, and its church, that of cathedral, by papal bull of 1404, that is, eighty-eight years before the foundation of the first American colony, which was no more than than a temporary camp, abandoned shortly after.

This is without mentioning a number of Castilian fortifications built on the Canary Islands, many years before the Columbian adventure: the towers of Gando (Gran Canaria), Añazo (Tenerife) and San Sebastián (La Gomera), the latter being the southernmost medieval European fortress among those that are currently preserved; as well as the dissappeared Valtarhais and Riche-Roche strongholds (Fuerteventura), previous to those mentioned.

Moreover, before the first voyage of Columbus to America, and apart from the numerous smaller towns taken from the ancient Canarians, there were already several colonial cities and towns on the Canary Islands, some of which were newly founded: Santa María de Betancuria (Fuerteventura), Gran Aldea (today Teguise, on Lanzarote), San Sebastián (La Gomera) and, among others, in 1478, Real de Las Palmas (the city of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria at present), the first royal-founded overseas Atlantic colony.

Making own history visible

That the Canary Islands have been chosen as a set for the filming of numerous international film productions at least since the 1950s, is not an unknown issue; but in recent times, the number of medium and high budget films that make up the landscapes and population centers of the Archipelago in their scenes has risen significantly. However, what is intended in an absolutely majority in these cases is to simulate real or invented scenarios, located in other coordinates, and thus the Canaries have come to play on the big screen from the center of the Earth to outer space, going across a large part of the biosphere: Athens, Beirut, Casablanca, the Red Sea, the Philippines, Guinea, Fernando Poo, the South Pacific and East Africa, among others. Unfortunately, the Canary Islands have rarely incarnated themselves and given visibility to their own history.

Regarding this, and related to the topic we are addressing in this post, it is not without its point of irony that the film Oro (Gold), one of the last fictions inspired by events of the conquest of America, was filmed in the mountains of Anaga (Tenerife), and where the mystified eyes of the spectator will see Amazonian jungles, the memory of history will tell us that those same jungles and paths are the ones that the Guanches once defended against the invaders sent by the Crown of Castile.

Antonio M. López Alonso