Risco Faneque, in Agaete (Gran Canaria), one of the highest sea cliffs in the world (source: PROYECTO TARHA).

Fortunately, the project […] that aimed to turn the valley into a tourist exploitation has been paralyzed for the time being. However this threat, anti-ecological and made of irrational modernization, looms over what is called to be an archaeological-natural park, and not one of those horrifying tourist condensation spots.

Celso Martín de Guzmán (The ethnohistorical sources and their relationship with the archaeological surroundings of the Guayedra Valley and Tower of Agaete (Gran Canaria), 1977)[1]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

To the people of Agaete, Artenara and La Aldea (Gran Canaria) in support of their advocacy of their natural, cultural and historical heritage.

One of the most important legacies the ancient Canarians left to us is the rich indigenous toponymy treasured by the Islands. The cause of this survival would have to be found in the innocuousness of these place names from the perspective of the European invaders, to whom only the customs related mainly to the islanders’ religious cults and rituals would be intolerable, being obviously incompatible with the imposition of Christianity.

It is true that the authenticity of this inheritance is partially undermined by the conversion of the original phonemes to European spellings and sounds, and the inevitable distortions contributed by textual and oral transmission; However, this should not be an impediment to embrace without hesitation this manifestation of the islander heritage as absolutely our own and recognize the need, today more than ever, to maintain a strict vigilance on the preservation of these treasures.

We want to present this post as a small sample showing the loss of a part of these heritage jewels in the tide of times and to implicitly conclude the need for a preservation policy that fights the harmful side of the globalization phenomenon, resulting in the impoverishment not only of a particular people but of the entire human species.

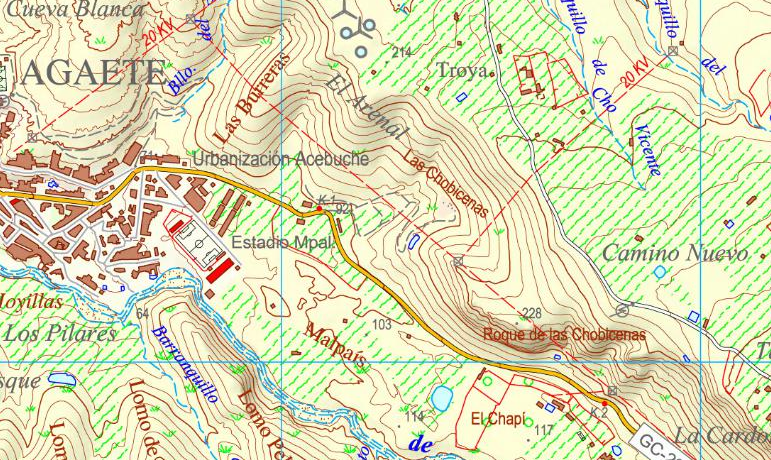

We will focus our small exploration on the surroundings of the Guayedra valley. The choice of this area is not casual: in recent times, the natural, cultural, historical and archaeological values of this region of Gran Canaria have been subject to a double threat. On the one hand, the environmental disaster posed by the rabogato or crimson fountaingrass (Pennisetum setaceum) plague, extended to practically the entire Canarian archipelago. On the other hand, the urban, infrastructural and tourist pressure, attracted by the exceptional beauty of the western landscape of the Island: long sunsets, high cliffs that fall over the sea and secluded coves on a rough, relatively little anthropized land.

Recent incarnations of this pressure, such as the controversy raised by the sale of Guguy / Güi-Güi natural place, finally resolved in favor of the public interest, the closure of the insular motorway ring, and, finally, the extension of the dock of Puerto de Las Nieves, facing strong popular opposition, constitute a brief sample of the processes endangering the natural, historical and cultural values of the area.

Risco Faneque from El Risco ravine. Note the spreading of pennisetum setaceum or crimson fountaingrass (source: PROYECTO TARHA).

Guayedra Valley

Much of the spectacle that can be seen from Puerto de Las Nieves is due to the presence of Guayedra Valley, a wide basin bounded by the hills that rise from Roque de Las Nieves, adjacent to the village port, the cliffs and narrow ravines descending from Tamadaba pine forest and the impressive mass of Risco Faneque, considered one of the highest coastal cliffs on Earth.

The historical importance of Guayedra is that, according to ethnohistorical sources, this valley was requested by Don Fernando Guanarteme, one of the last indigenous chieftains of Gran Canaria, to the Catholic Monarchs as a término redondo (round boundary) and in payment for the services rendered by him in favor of the submission of the Island to the Crown of Castile, an award that was officially granted by Governor Pedro de Vera in 1495. It should be noted here that the term round boundary in ancient Castilian laws does not necessarily imply seigneurial jurisdiction, but property exclusively on pastures and cattle included in the limits of a suitably marked land.

From these sources we cannot extract a priori any specific cause to motivate the preference of Fernando Guanarteme for these lands, a choice that even surprised the grantors themselves given their harsh and semi-arid nature. The speculations in this regard have been many and varied: from their configuration as a sort of indigenous reserve to the preservation of a sacred and / or cultual space, through a plausible identity as an ancestral home of the dominant lineage during the last stage of the ancient precolonial society. Neither the proximity of one of the hierophanic nuclei of greater relevance to the natives seems to be negligible: Tirma.

Guayedra Valley, whose round boundary was granted by the Catholic Monarchs to don Fernando Guanarteme as a reward for the latter’s contribution to Grandcanarians’ surrender to the Crown of Castile (source: Google Earth).

Las Chobicenas / Chibicenas

Let us begin our small toponymic sample with two names directly linked to a kind of tenebrous, polymorphic beings linked to the beliefs of ancient Grandcanarians: the tibisenas. Brother Juan de Abreu Galindo points out in this regard:

[the devil] appeared to them many times at night, and in the daytime like big shaggy dogs; and in other shapes which they called tibisenas.

Leonardo Torriani contributes a geographical hypothesis:

Among these Canarians there were men very brave at war. One of them was called Atazaicate, which means courageous and big-hearted; but, being ugly, women named him Atabicenen, that is, wild or shaggy dog; because tabicena in their language means dog; from where some have thought that formerly among these Canarians the island was called Tebicena, which would mean the same as Canaria.[2]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

The curious thing about the place names Las Chobicenas / Las Chibicenas is that they are not located in places separated from each other, but they appear in four physically contiguous, paired locations on maps: Las Chobicenas and Roque de Las Chobicenas, both east of Agaete village centre; and Las Chibicenas and Las Chobicenas, in the middle of Cortijo de Guayedra. Regarding its origin, some authors relate it to the ancient practice of witchcraft in Agaete, and in the case of the last two place names it would not be unreasonable to suppose a relationship with the dark and narrow ravines that cut the cliffs of Tamadaba and pour their waters into the Valley

Antigafo

But the most interesting collection of disused place names related to Guayedra Valley is offered by public documentation, specifically by the historiographically known as Deslinde de Guayedra (Guayedra Demarcation): in 1512, Miguel de Trejo, son-in-law of the late Fernando Guanarteme, complaint to the colonial authorities the damage caused by the interference of alien people and cattle into Guayedra Valley, being the latter inherited by his wife and daughter of the deceased, Margarita Fernández Guanarteme, so Trejo requested the demarcation of the place, taking care of the task three specialists: Miguel de Gran Canaria, Salvador Canario and Juan Benito, neighbors of Agaete and also indigenes, for what is inferred from at least two of their surnames, and attesting to the act the notary of Gáldar, Alonso de Herrera. The testimony of this public servant, inserted in subsequent documents, has been transcribed and studied in two articles essential for the knowledge of local history: The ethnohistorical sources and their relationship with the archaeological environment of the Guayedra Valley and Tower of Agaete (Gran Canaria), published by Professor Celso Martín de Guzmán, and The Guayedra estate and the inheritance of Agaete before royal occupation, by Professor Vicente J. Suárez Grimón.

In Professor Martín de Guzmán’s transcription we can read the following:

[…] in the presence of me said Notary and of the witnesses written afterwards that being inside the boundaries of Aguaete on the plateau that goes up from a path that is above of a high cliff which is next to and in front of the tower of the said Town of Aguaete being present the said Michel and Salbador and Juan Benito surveyors and demarcators named by the Governor himself who said […] that it was the boundary with ancient landmarks of the Guajayeda Valley in the round boundary that Dn. Fernando Guadarteme and his son-in-law Miguel de Trexo had previously possessed that was given to him from the plateau that at the present time we were on and having our feet which had name Antigafo, in the language of the ancient Canarians across the waters to the other end of said Valley […][3]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

Martín de Guzmán does not hesitate to identify this Antigafo plateau with the current Roque de Las Nieves. On the other hand, Professor Suárez Grimón gives us a somewhat different reading of this fragment:

From the Plateau that at present we were on and had our feet, which had (as) name Antigafo, in the language of the ancient Canarians les Aguañe, to the other end of the said valley of Guadayeda;[4]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

Roque de Las Nieves, at whose foot the Tower of Agaete was built. The nearby plateau was named Antigafo by the ancient Grandcanarians (source: PROYECTO TARHA).

Magaden and Taxanicuvidagua

For not making this post reading cumbersome, we omitted part of the testimony regarding the demarcation itself, referring the readers to the respective transcripts collected in the selected bibliography. However, we cannot fail to mention its most interesting fragment including one of the few translations of a Canarian toponym into the Spanish language. Professor Martín de Guzmán continues:

Item up above these markers and fences there is a grave of Canarians which said surveyors left as a marker and it is by the road of firewood going up to Tamadaba and from up there they made a marker in the middle of the path leading to mocanal and to Tamadaba going round along to a plateau the said surveyors say to be called Magaderre, which is a name by those on Gran Canaria, which leads into a path going to Tatirma which has a name in the language of the Canarians Etaxanicavidagua which in Castilian language pais del Palo [sic, Paso del Palo, Pass of the Staff] as the said surveyors said, at which pass a marker was put and marked in the middle of the said path and pass and they put another two markers at the upper end of the said path, and another two markers at the lower end against the sea.[5]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

And Professor Suárez Grimón reads:

Item, up above these markers and fences there is a grave of Canarians, which said surveyors left as a marker and it is by the Path of Firewood going up to Tamadaba and from up there they made a marker in the middle of the path leading to Mocanal and to Tamadaba and so going up the rock rim leading to the cliffs of Tamadaba, and along the cliffs of Tamadaba Mountain going round onto a plateau the said surveyors say to be called Magaden, which is a name by those on Gran Canaria, which leads into a path and pass going to Ayatirma which has a name in the language of the Canarians Taxanicuvidagua which is in Castilian language Paso del Palo [Pass of the Staff], as the said surveyors said, at which pass a marker was put and marked in the middle of the said path and pass, and they put another two markers at the upper end of the said path, and another two markers at the lower end against the sea.[6]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

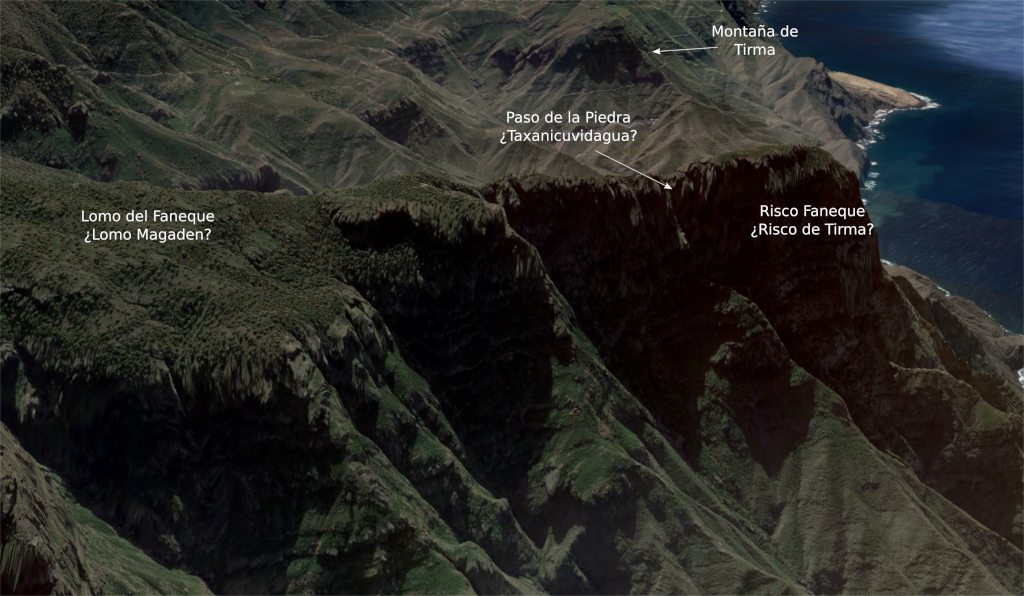

What was the exact location of these two places? Although both toponyms have disappeared in their original form off the maps, it is unquestionable that they were on the periphery of the Guayedra Valley, whose boundaries would be clearly delimited by the basin’s own morphology: from the Roque de Las Nieves, vertex of a line of rims and plateaus ascending to the edge of Tamadaba pine forest, along this border –maybe following a path similar to that of the current Tamadaba ring road– to the top and foot of Faneque cliff, and, following the coastline, back to Roque and Lomo de Las Nieves or Antigafo.

Therefore, it may not be a hurry to identify oronym Magaden with the current Lomo del Faneque. Following this first assumption, and taking into account the hypothesis that we will raise in the next section, the Taxanicuvidagua or Paso del Palo (Pass of the Staff) would possibly coincide with the current Paso de la Piedra (Pass of the Stone), the path that gives access to the tip and top of Faneque. And, of course, the danger involved in traveling this path would fully justify the indigenous denomination, a sort of stress test that requires trekkers maximum self-control and absolute absence of vertigo. It should be noted that Professor Martín de Guzmán indicates that the place name Paso del Palo corresponds to one of Tamadaba cliffs, although we have not found this reference in the current cartography.

A second possibility is inspired by the existence of the place names Hoya del Paso del Palo and Paso del Palo in a place relatively close to the Guayedra Valley, although outside the latter’s natural limits; specifically, on the northwest slope of Altavista Mountain, a geological landmark that we would have then to identify with the Magaden plateau. This possibility is supported by the fact that the path beginning at this Paso del Palo forks several times leading, among other places, to Tirma Mountain and El Risco neighborhood. If this theory is true, it would surely be necessary to extend the boundaries of the Guayedra demarcation to include Tirma sacred ground, which would be consistent with the important role played by Fernando Guanarteme in the ancient Grandcanarian society. However, as we justify below, we do not believe that this possibility has much weight.

Is Tirma Mountain, Tirma?

Let us note that the cited testimony indicates the surveyors marked the beginning and the end of the path to and from the Taxanicuvidagua with a pair of landmarks at each end, interior and coast, in addition to marking the middle point of that road with an additional stonepile. Therefore, and unlike what happened during the ascending stretch of the survey, during the descent the technicians did not lavish themselves placing marks, from which it can be deduced with total certainty that either the road lacked detours that could lead to confusion, or its route was relatively short, or these two circumstances occurred. These assessments lead us to consider our second case unlikely, since the Pass of the Staff adjacent to Altavista is quite far from the coast and does fork into several trails, factors that would advise providing its route with a greater number of signals.

Now let us have in mind the expressions transcribed by the professors Martín de Guzmán and Suárez Grimón: a path going to Tatirma and a path and pass going to Ayatirma. For now, we have not been able to access the documents in which these fragments appear, but since these are late copies, querying them may not provide us with more information than that offered by these experts.

In any case, it is worth dwelling on the fact that the path starting at the Taxanicuvidagua leads to Tatirma or Ayatirma, a toponym appearing in the public documentation of the 19th century, designating a palm grove located at Tamadaba Mountain, while other opinions place it in the current neighborhood of El Risco. Note that Francisco López de Gómara calls Ayatirma the great rock from which the ancient Grandcanarians threw off offering themselves in sacrifice. On the other hand, it is clear from the morphological characteristics attested by other ethnohistorical sources that Tirma cliff must have been an outstanding and challenging orographic landmark. For example, Cronica Ovetensis indicates a cliff they called Tirma; and also that:

[…] these Canarians had for sanctuary two cliffs called Tirma and Cimarso[sic, possibly for Amagro], which have two leagues each around, bordering the sea, and whoever malefactor taking shelter on these mountains was free and safe, and they could not get him out of there if he did not want to, keeping them and venerating them like a church […][7]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

being understood that two leagues were equivalent to a distance of two hours on foot or ten kilometers, although matching distance and time was not essential.

In general, the nexus common to the first accounts telling about Tirma is the mention of a high and undoubtedly imposing cliff bordering the sea. However, what is known in the cartography as Tirma Mountain lacks such spectacularity, dangerousness and altitude, attributes clearly appreciated by the indigenes in accordance with colonial stories, and predictably enhanced by the presence on the horizon of the Teide volcano, the island of Tenerife and the beautiful sunsets, being the Sun worshiped by the ancient Grandcanarians under the theonym Magec.

On the other hand, keep in mind that the oronym Faneque, of plausible amazigh etymology, was probably introduced in colonial times. As an example, the testament of Captain José Cabrejas, initiated in August 1678, presents it to us in its primitive form as Afaneque; that is to say, alfaneque, name that receives one of the multiple subspecies of falconidae, represented in the case of Gran Canaria by the tagarote or Barbary falcon (Falco pelegrinoides), a bird of prey nesting in the rocky walls of this part of the Island. Note this time that the pass starting the descent towards the sea, to the base of the cliff itself, is called Paso Blanco (White Pass):

From Roque de las Nieves, up the plateau above Maneo leading to the Degollada, from there up to Tamadaba, falling waters to a pass upon «Afaneque» they call Paso Blanco, leading to the sea, the shore ahead going to the same Roque.[8]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

Consequently, it is very plausible that the true and historical cliff of Tirma is Faneque cliff itself, although, naturally, this does not prevent the past existence of a sacred area of greater extension, which would cover the zone currently known as Tirma Estate and Mountain, as well as the ravine and neighborhood of El Risco de Agaete.

Being true or not our hypothesis, contemplation of the always imposing, overwhelming presence of Faneque Cliff, either from the viewpoint of Tamadaba, Puerto de Las Nieves, or the view from its very top of a landscape that makes the senses insufficient, urges the unappealable protection of this wonderful environment and the dissemination of its natural and historical treasures, which should not be given another price than to transmit them intact to future generations.

Antonio M. López Alonso

References

- López de Gómara, F. (1553). Primera y secunda parte de la historia general de las Indias co[n] todo el descubrimiento, y cosas notables que han acaescido dende que se ganaron hasta el año de 1551 : Con la conquista de Mexico, y de la nueua España. Medina del Campo: Guillermo de Millis

- Martín de Guzmán, C. (1977). “Las fuentes etnohistóricas y su relación con el entorno arqueológico del Valle de Guayedra y Torre de Agaete (Gran Canaria)”, Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos, vol. 1, num. 23, pp. 83-124. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Cabildo de Gran Canaria

- Morales Padrón, F. (1978). Canarias: Crónicas de su conquista. Sevilla: Excmo. Ayuntamiento de Las Palmas – El Museo Canario

- Suárez Grimón, V. J. (1973). “La hacienda de Guayedra y el heredamiento de Agaete ante la ocupación de realengos”, Revista de historia canaria, vol. 37, num. 173, pp. 91-97. La Laguna (Tenerife): Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de La Laguna

Uno de los legados más importantes que nos dejaron los antiguos canarios es la riquísima toponimia indígena que atesoran las Islas. La causa de esta supervivencia habría que hallarla en la inocuidad de estos nombres de lugar desde la perspectiva de los invasores europeos, a los que únicamente les resultaría intolerables los usos y las costumbres relacionadas principalmente con los cultos y rituales religiosos isleños, incompatibles a todas luces con la imposición del cristianismo.

7 comments on “Taxanicuvidagua: The Pass of the Staff”