Idealized statue of Pedro Hautacuperche located at Valle Gran Rey, La Gomera, by sculptor Luis Arencibia. He is holding in his right hand the Ganigo of Guadajume, already broken, and in his left hand the weapon with which he killed Fernán Peraza the Younger, giving rise to the uprising of La Gomera in 1488 (source: Erik Baas / Wikimedia Commons).

To the Gomeran people, brave and beautiful, with love and respect.

November 1488. A man dressed as a woman falls murdered in the vicinity of a cave. Soon after, on the wings of an ancestral whistling language, the echo of the deep ravines on La Gomera carried a war cry: “Now the Ganigo of Guadajume is broken”.

The victim was Fernán Peraza the Younger, the Castilian Lord of the Island and Doña Inés Peraza’s favorite son, who a few months before had constituted in the second of her male offspring the entail of the Seigneury of the Isles of Canaria, which had been de facto extinct for more than ten years before. The executioner, Pedro Hautacuperche, a pastor who shepherded his flock on Plan de Asisel, in front of the imposing massive Agando Rock.

Tradition among Gomeran natives states that theirs was the only one of the Canary Islands that was never conquered by Europeans. But the truth is that the death of the Castilian Lord was met by one of the most cruel retaliations carried out on the Archipelago ever.

Background

However, this popular belief has some historical basis, since there is no reliable evidence that Gomeran indigenes were completely subjugated by European forces until such repression. Although some late authors point out that Jehan de Béthencourt had conquered La Gomera, there is no documentary or circumstantial evidence of this, and even selfsame Le Canarien chronicle silences this supposed achievement of the Norman nobleman.

What is sufficiently verified is the good relationship that existed, from at least the 1440s, among ancient Gomerans and the Kingdom of Portugal. According to the Portuguese chronicler Gomes Eanes de Zurara in chapter LXVIII of his Chronica do descobrimento e conquista da Guinée[1]Free translation by PROYECTO TARHA.:

There two captains arrived from that island [La Gomera], saying how they were servants of Prince Dom Henrique, and not without great reason, since they had already been in the house of the King of Castile and the King of Portugal, and never in any of them found the mercies that later they get from Prince Dom Henrique; […] Bruço, was named one of these captains, and the other Piste, who responded together they were happy to work on anything that was at the service of Lord Prince Dom Henrique, […]

This predisposition towards the Portuguese prince undermined the success of the conquest carried out in the triennium 1445-1447 by Fernán Peraza the Elder, III Lord of the Isles of Canaria and the victim’s maternal grandfather, who had to resign himself to the erection of a fortress –perhaps the current Torre del Conde– and the adhesion of only one of the tribal chiefs, according to one of the most prominent and informed witnesses, the camera scribe Juan Íñiguez de Atabe, in Cabitos’ Inquiry:

[…] he heard that the said Ferrand Peraça [the Elder …] conquered the island of La Gomera […] and he made a tower on it, and because he showed greater favor to one captain of the Canarians on it, because he was the first that came to his obedience, other captains on the said island rebelled against him and uprose for Prince Henry of Portugal, […]

The weakness of the Seigneury of the Isles of Canaria, further reduced by its own material limitations, and the Portuguese interest in the Island were factors that the indigenes knew how to use decisively to their advantage, in such a way that Castilian colonization and evangelization had little impact on their way of life. Thus, before Pérez de Cabitos, witness Juan Ruiz de Zumeta:

[…] knows that the Island of La Gomera since the time of Ferrand Peraça [the Elder] is obedient to the Seigneury […] as to rights, but as to the faith they live as it suits to them and they have not some of them for true christians.

Statement also signed by the witnesses Fernán Guerra and Juan Bernal. But undoubtedly the most explicit testimony is provided in 1492 by the Peraza’s widow, Beatriz de Bobadilla, before the Royal Council:

[…] said Gomerans were not Christian nor have been they, and should they had [a christian] name no Christian deed they did, and not caring about being baptized, calling themselves gentile names, living naked, and having eight or ten women, not consenting Christians among them, on the contrary taking them and making them many other superstitions to all their Christian women; […]

The previous scenario, favorable to the natives, had to transform gradually into a dominant position of the Seigneury as a result of three events. The first, the marriage union, probably at the end of the 1460s, of Diogo da Silva and María de Ayala, sister of the young Fernán, implying a tacit alliance of the Herrera-Peraza family with the Portuguese crown; the second, the failure of the Portuguese fleet sent in 1478 to prevent the Castilian conquest of Gran Canaria; and the third, the signing, in 1479, of the Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo by which the Kingdom of Portugal recognized the sovereignty of the Crown of Castile over the Canary Islands, among other rights.

These latter two events gave the coup de grace to the intention of Inés Peraza to restore the Seigneury of the Isles of Canaria with the help of her son-in-law, Diogo da Silva de Meneses, future Count of Portalegre and influential member of the Portuguese court. Therefore, the last resort for the Herrera-Peraza was to shore up their already diminished authority over the islands they still kept: Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, El Hierro and La Gomera, which undoubtedly entailed the application of much more coercive policies on their islander vassals.

The four parties

The ethnohistorical sources show that ancient Gomerans were organized into four parties, called Ipalan, Orone, Agana and Mulagua, among other consigned variants. Usually these sides are interpreted as clear territorial demarcations, a thesis that suffers from a certain comparative inertia, undoubtedly coming from the explicit physical divisions witnessed on other islands such as Gran Canaria, Tenerife and La Palma.

However, it is not at all clear that the Gomeran parties corresponded to spaces of political geography, although some sources say so. Firstly, because it is difficult to find a satisfactory match between these names with present place names on the Island, since only locations Veguipala and Hermigua seem to have respective similarities with the Ipalan and Mulagua sides –the latter stands as Amilgua or Armigua in certain sources–. And secondly, because a comparative reading of the ethnohistorical accounts does not allow us to assert that these sides were anything other than four tribal lineages, although this does not prevent the presence of each one of them being more prominent in certain population areas.

“Ferrando el capitán de Mulagua” (Ferrando the captain of Mulagua), one of the four Gomeran parties, appears in the final letter of the sentence of freedom for Gomerans imprisoned by Fernán Peraza in 1477 (source: Archivo General de Simancas, RGS, LEG, 147802, 119).

Prelude to rebellion

The disaffection of the Gomerans towards the Castilian lords was the germ of an indeterminate number of conflicts between both parties whose documentary evidence is currently scarce. Let’s mention the best known ones. In 1477, Fernán Peraza the Younger, under the pretext of organizing the capture of a small carrack, disembarked on La Gomera the crews of some caravels from Palos de la Frontera and Moguer that dedicated themselves with impunity to capture more than a hundred Gomerans of both sexes, among which was Ferrando, the captain of Mulagua, being some of them sold in the slave markets of both towns and Jerez de la Frontera, and the rest being deported to other islands.

The action was denounced by Don Juan de Frías, Bishop of Rubicon, who alleged that the detainees were faithful Christians who fulfilled their obligations as such and, therefore, could not legitimately be condemned to slavery.

The case raised a serious problem of social order if it was not stopped in time: the second Castilian Partida specified that only those who fall under power of men who follow another faith were susceptible to slavery. Not to set a precedent of undoubtedly disastrous consequences, the Catholic Monarchs ordered their lawyers to investigate the case, and these, giving the reason to the prelate and sentencing the six caravel responsibles to pay the costs of the process, ordered the search and immediate release of the captives, many of whom returned to the Archipelago aboard the armada sent to conquer Gran Canaria in 1478.

In May 1478, the monarchs of Castile ordered the captains of that armada to lend support to Fernán Peraza to quell a sedition on La Gomera, possibly motivated by the events of the previous year, but this time Peraza had denounced that, in addition to denying obedience and rents, the dissidents gave shelter to Portuguese agents. Peraza only exempted from these charges the members of Orone party, who were always loyal.

As we said, the Herrera-Peraza had been related to an important courtier from Portugal. Therefore, it seems reasonable to guess a triple game in the attitude of the young lord: liquidate the Gomeran opposition to his person, weaken the forces sent to the royal conquest of Gran Canaria to facilitate the Portuguese intervention in the area, and alleviate the logical suspicions of collaborationism that would weigh on the manor house, increased by the war of succession to the Castilian throne waged among the Catholic Monarchs and Afonso V of Portugal.

Finally, by the testimony of Beatriz de Bobadilla, we know that, at the beginning of the 1480s, Fernán Peraza entered into a pact with the Gomeran parties, acting as a mediator a so-called dean of St. John and other people, for which the islanders promised to abandon their pagan practices and be good Christians or, if they did not do so, they could be conquered and given in captivity and perpetual servitude. An agreement that, according to Bobadilla, the Gomerans never fulfilled.

In fact, in August 1484, the Catholic Monarchs sent a demanding letter to the residents on La Gomera ordering them to comply with Fernán Peraza’s lordship, because, as in 1478, he had complained to the Crown that his vassals refused to obey him.

Tales of an assassination

Four years after this last event took place the one concerning us. What do ethnohistoric sources tell us about it?

Following Cronica Ovetensis:

Belonging to these two latter parties and lineages [Ipalan and Mulagua] there was a beautiful Gomeran woman they called Yballa, it was her surname [sic. by nickname], to whom the lord of the island Hernán Peraça took a liking [who] could not neither abstain nor stand so close to the hand as to not upset those to whom that good lady was blood related, who made a case of virtue and considered themselves insulted among the other parties as in despite of they knew it all, he had taken her and had her as a mistress, and so they gave themselves a way to take revenge and to restore their lost honour or received insult, and for that they agreed to kill him. Finally they waited for him a night to enter and be with her, and when he left, they were waiting for him and they killed him, […]

Cronica Matritensis expresses itself in similar terms, although generalizing Peraza’s love to some Gomeran women:

[…] it was an offense for those to whom she was related and they ordered to kill him, and brought some spies upon him until they took his life.

Francisco López de Ulloa:

Finally they waited for him for one night to walk in and be with her. And when he left, they were waiting for him and they killed and speared him, […]

Pedro Gómez Escudero:

[…] as the other parties told these they were indulgent with Yballa, they set out to undertake the following case: they waited for their lord to be inside that house, and on leaving they threw themselves at him stabbing him.

But the most well-known and descriptive stories of the event were provided by Brother Juan de Abreu Galindo and Tomás Marín de Cubas, although they differ among themselves in terms of some of the data they offer. Abreu Galindo begins his version of the events with a revolt in 1488, days before the murder, which forced Fernán Peraza to take refuge in his Gomeran fortress and which was harshly repressed by Pedro de Vera, governor of Gran Canaria. After quelling this rebellion, Peraza worsened the treatment of his vassals.

Although warned of the consequences of his attitude by Pablo Hupalapu or Chapulapu, an old man revered by the other indigenes, Peraza not only did not allow himself to be persuaded, but rather he hardened the rigor of his government, and then three Gomeran leaders met on or by a rock next to Taguluche village to discuss the solution to the problem that finally was, according to Abreu Galindo, to kidnap Peraza or, according to Marín de Cubas, to kill him. The latter author also tells how one of the conspirators was killed by his companions after he was hesitating about the convenience of the action they were preparing to execute.

We warn here of the erroneous belief that locates the place of the conspiracy on a rock that emerges in front of Valle Gran Rey beach, because this idea has its origin in a historical tale published in 1900 by Lanzarote writer Benito Pérez Armas, entitled La Baja del Secreto –The Secret’s Reef–. As for the Taguluche rock, Marín de Cubas places it into the sea while Abreu Galindo does not pronounce himself on its location. Therefore, it is not rejectable to identify it as one of the ravine rocks next to this location.

Taking the decision, the conspirators and their henchmen waited or organized that a proper occasion was given to carry out their plans, and nothing more favorable than using the Lord’s mistress. Although warned by his servants of how dangerous was to date Yballa, Peraza left for the place of their meetings, a cave house located in the place of Guadajume, where the Lord owned some seeded plots, about twenty kilometers from San Sebastián, which tradition identifies with the present Chinea’s Cave. Abreu Galindo dates the meeting in the month of November of 1488, while historian Pedro Agustín del Castillo provides a specific day: November 20, although the year 1489. We really do not know the quality and the source of this information but anyways, checking the existing public documentation on the case, we must reject the year 1489, so, if we combine both authors’ criteria and trust them, we would have to date the event on November 20, 1488.

Accompanied by at least one servant, Fernán Peraza dismounted in the vicinity of the cave, telling his server to wait for him away with the horse. Once he joined Yballa, an old woman, a relative of the young one, warned the conspirators of the presence of the lord in the cave through the ancestral whistling language, and these, leaded by another relative, pastor Pedro Hautacuperche or Jauta Cuperche, proceeded to surround the cave. Both Abreu Galindo and Marín de Cubas point out that Yballa convinced Peraza to disguise herself as a woman and thus try to elude his captors.

But Abreu Galindo, with his accustomed idealizing and chivalrous style, makes Peraza, refusing to avoid combat and the disgrace of dying wearing female clothes, return to the cave and give him time to shed the disguise, put on his armor, take his sword and leather shield and stand up to face his enemies at the entrance of the refuge, only to fall inmediately pierced from the neck to the side by Hautacuperche’s spear head, who thrown himself from above the shelter.

On the other hand, Marín de Cubas shows authenticity, not without some poignance, in the scene he describes: while Fernán Peraza runs dressed in woman clothes towards the horse waiting by the servant, he hears Yballa’s warning cry, urging to flee to save life. And the servant, although he watches his master being chased by a group of men, takes advantage of the mount and escapes at a gallop, while Hautacuperche reaches the distraught Peraza in the back, killing him immediately.

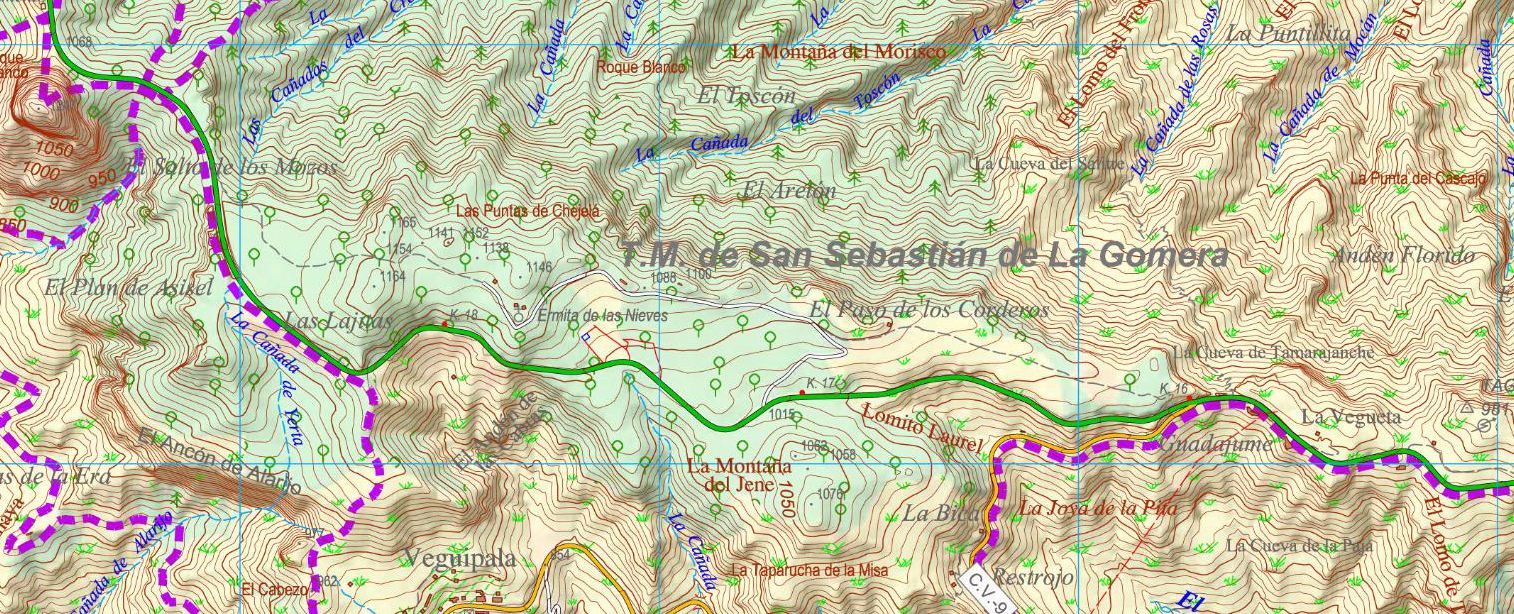

Partial topographic map of La Gomera showing the place names Plan de Asisel on the left, Veguipala on the lower end and Guadajume on the right (source: IDE Canarias / Government of the Canaries).

A philological jewel: «Ajeliles, juxaques aventamares»

As if that were not enough, Marín de Cubas surprises us in his story with one of the few phrases in the indigenous language that were preserved in the Canary Islands: precisely the apostrophe, the cry Yballa pronounced and which, almost with total certainty, was directed to Peraza’s servant, perhaps a Gomeran man who belonged to the party of Orone, since it is unlikely that the Castilian could understand the native language.

The phrase is «ajeliles, juxaques aventamares», which Marín de Cubas translates as «run away, for they are going to get you». In the draft of his work, completed in 1687, Marín de Cubas had written it in the form «ajeliles juja que es aventamares».

As is to be expected, this apostrophe has aroused a lively interest among the philologists who investigate the ancient Canarian language. The first classic work in this regard is the monograph by Professor Georges Marcy, entitled The apostrophe directed by Iballa in Guanche language to Hernán Peraza, published in the magazine El Museo Canario in 1934, but also of interest are the analyzes by professors Dominik Josef Wölfel, Juan Álvarez Delgado and Dr. Ignacio Reyes García.

A colactation pact?

As we said at the beginning of this post, after Fernán Peraza’s death, his killers spread a slogan throughout the island that was collected by both Abreu Galindo and Marín de Cubas. Let’s see these testimonies, beginning with the Franciscan’s:[2]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

Gomerans who killed Peraza, upon the hills, said in their language «now the ganigo of Guahedun broke», and a ganigo is sort of a big clay pot in which many eat together, for they all were going to make reverence and obeisance to Hernán Peraza, they said they were going to drink milk in him like a ganigo.

And that by the doctor and lecturer, very similar, which indicates they shared references:

[…] the Gomerans said as a proverb now the ganigo of Guachedun broke where everybody was going to drink milk; and it was because they were going to welcome him when he came to the country property.

It sometimes happens that a historiographical hypothesis becomes so popular that it ends up being interpreted as a confirmed fact, without any demonstration of any kind. This is the case of the thesis that infers from the above slogan the previous celebration of a colactation pact among the Gomeran chiefs and Fernán Peraza, that is, an agreement the parties sanction drinking milk, usually from the same recipient; in this case, an indigenous-made ganigo or clay pot.

This hypothesis was raised and defended by Professor Juan Álvarez Delgado (Güímar, Tenerife, 1900 – Santa Cruz de Tenerife, 1987) in one of his extensive articles, titled The episode of Iballa, based on the existence of pacts of a similar nature among some continental Berber tribes and on a presumable error of interpretation, on the part of Abreu Galindo and Marín de Cubas, about the true meaning of the slogan, premises that the expert himself assumed as guarantors of his theory:[3]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

Among the different types of pacts, the alliance pacts with milk rites practiced in different parts of the North African Berber world are of special interest for our current problem. […]

As the Gomeran slogan speaks of «a ganigo» and the chroniclers say that «they were going to drink milk», I deem the formula or rite practiced with Hernán Peraza was the latter. […]

With these data the interpretation I give to the texts of our chroniclers will be well understood, although naturally these historians did not understand either the importance or scope of the event they inform about, nor the symbolism of the rite enclosed in the phrase they transmit, […]

As we have seen before, execution of pacts among Gomerans and Fernán Peraza are documented, but we barely know the exact circumstances in which they occurred, much less the protocols that were observed in their rubric. However, we must admit that it is difficult to imagine Inés Peraza’s son adapting himself to indigenous rituals of pagan origin, interested, as he was, in making his vassals definitively embrace Christian life and customs.

No less strange, even sarcastic, is that the unilateral cancellation of the supposed pact, symbolized by the physical or imaginary breakdown of the ganigo, takes effect after one of the signing parties has made the other disappear. Logical would be to break or give up the contract prior to the punitive act, but not the other way around.

Politics and incest

With the exception of Abreu Galindo, for whom the murder of Fernán Peraza has exclusively political motivations, the rest of the testimonial sources adduces causes of honor as impellers of the case, based on the erotic relationship between the Castilian and Yballa. However, Professor Álvarez Delgado supported the thesis by the alleged friar arguing that an insult of this nature cannot be understood given the indigenous cultural context, since Gomes Eanes de Zurara testifies that the ancient Gomerans tolerated sexual hospitality among their customs, an assertion endorsed by the words of Beatriz de Bobadilla when she declared that men had eight or ten women, naturally, with all the caution that the particular interest of the witness forces us to take.

However, in 1986, twenty-seven years after Álvarez Delgado’s writing, Professor Francisco Pérez Saavedra adds a new hypothesis to the philologist’s approach in the form of an article, significantly entitled The episode of Iballa and its motivations, which justified the cause of honor adduced by most ethnohistorical sources:[4]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

The pact of Guahedún, understood by Peraza and the Castilians as an act of seigniorial submission, for the indigenes was a colactation alliance that turned the aforementioned Peraza and the indigenes who drank with him the milk from the same ganigo in “milk brothers”, relatives belonging to the same clan. And this entailed, by virtue of the general rule of exogamy that governs dualist organizations and the taboo of incest […] that any relationship with women of the same social group in which they entered or to which they belonged were prohibited, constituted an abominable act, whose disastrous consequences affected everyone collectively.

To support his theory, Pérez Saavedra resorts to an ethnographic note that Álvarez Delgado deemed as false, that is the Gomeran parties, according to the account by Pedro Gómez Escudero, were related two by two. Pérez Saavedra interprets this datum as symptomatic of a dualist organization, in which relations of interpersonal relevance –marriages, councils, parties, etc.– are restricted to the members of each pair of clans. Therefore, if Fernán Peraza had agreed to an alliance in which Yballa’s belonging clan was involved, his relationship with the Gomeran woman must have been interpreted as incestuous, and this made him worthy of the death penalty.

Conclusion

Although the attractiveness of the colactation pact’s hypothesis is undeniable, it is not trivial to demonstrate its presumed translation from the cultural scope of continental Berbers to the Canary Islands, as long as the origin of the former islanders, and in particular that of the Gomerans, coincides with the locations where the practice of these rites has been observed, both in their spatial and temporal dimensions.

In any case, we cannot rule out, contrary to Professor Álvarez Delgado’s opinion, the interpretation given by Abreu Galindo and Marín de Cubas about the enigmatic Gomeran slogan could be close to the truth of the facts.

After all, it may be that, as these historians suggested, the Ganigo of Guadajume was nothing more than the circumstantial personification of Fernán Peraza in an object that his Gomeran vassals used to lavish on him whenever they welcome him, as an advance of the fruits they were obliged to deliver each time he claimed the rents of his fiefdom. A messianic personification that, possibly, Peraza himself tried to encourage: he was the chalice, the ganigo everyone was going to drink from, and that one noon of 1488 they decided to break forever.

(Ahehiles, written and composed by Rogelio Botanz and Pedro Guerra for the LP Identidad –1988-, by Canarian folk band Taller).

To be continued…

Antonio M. López Alonso

References

- Abreu Galindo, Fr. J. de (1848). Historia de la conquista de las siete islas de Gran Canaria. Santa Cruz de Tenerife (España): Imprenta, Lithografía y Librería Isleña.

- Álvarez Delgado, J. (1959). “El episodio de Iballa”, Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos, vol. 1, núm. 5, pp. 255-374. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (España): Cabildo de Gran Canaria.

- Arias Marín de Cubas, T. (1937). Historia de la Conquista de las siete Yslas de Canaria. Telde (Gran Canaria) (España): Archivo de don Pedro Cabrera Benítez.

- Arias Marín de Cubas, T. (1986). Historia de las siete islas de Canaria. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (España): Real Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País de Gran Canaria.

- Aznar Vallejo, E. (1990). Pesquisa de Cabitos. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria – Madrid (España): Cabildo Insular de Gran Canaria.

- Azurara, G. E. de (1841). Chronica do descobrimento e conquista de Guiné escrita por mandado de El Rei D. Affonso V, sob a direcção scientifica, e segundo as instrucções do illustre Infante D. Henrique, pelo chronista Gomes Eannes de Azurara; […]. París (Francia): J. P. Aillaud.

- Marcy, G. (1934). “El apóstrofe dirigido por Iballa en lengua guanche a Hernán Peraza. Notas lingüísticas al margen de un episodio de la historia de la Gomera”, El Museo Canario (nº 2), núm. 2, pp. 1-14. Madrid (España): El Museo Canario.

- Morales Padrón, F. (1978). Canarias: Crónicas de su conquista. Sevilla (España): Excmo. Ayuntamiento de Las Palmas – El Museo Canario.

- Pérez Saavedra, F. (1986). “El episodio de Iballa y sus motivaciones”, Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos, vol. 1, núm. 32, pp. 417-443. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (España): Cabildo de Gran Canaria.

- Rumeu de Armas, A. (1969). La política indigenista de Isabel la Católica. Valladolid (España): Instituto “Isabel la Católica” de Historia Eclesiástica.

- Wölfel, D. J. (1930). “La Curia Romana y la Corona de España en la defensa de los aborígenes Canarios. Documentos inéditos y hechos desconocidos acerca de las primicias de las misiones y conquistas ultramarinas españolas”, Anthropos, vol. 25, pp. 1011-1083. Viena (Austria): Anthropos Institut.

Pingback: La memoria colectiva y la "rebelión de los gomeros" ✅ La Gomera