“Tanausú, Tierra y Nobleza” (Tanausu, Land & Nobility) (2016), an idealized picture embellishing the facade of Casa de la Cultura Braulio Martín Hernández in El Paso (La Palma), a work by Lanzarote-born muralist Matías Mata, nicknamed Sabotaje al Montaje (source: PROYECTO TARHA).

For La Palma, our Benahoare, nowadays in such a need of strength and courage.

In the traditional historical memory of the Canaries, individuals belonging to the precolonial island societies who faced the European Conquest with the technological and numerical disadvantage inherent to their way of life, environment, material resources and demographics who sometimes chose to sacrifice their own lives rather than surrender are bestowed the role of true people’s heroes regardless of whether the referred subjects enjoyed any sort of privileged social status.

Recognizing that this phenomenon happens not exclusively to the modern Canarian society does not downplay its singularity roots in the fact that these persons belonged to social structures and cultural basis that were decimated by warfare and the aculturation and deculturation processes propelled during and mainly after the conquest in such a way that barely some remains survived a few decades after the effective submission of each island and circumscribed almost only to the rural environment; consequently it turns remarkable that more than five centuries past the end of the conquest of the Archipelago a considerable part of the Canarian folklore assembles itself around vindication, identification and even threading of both material and immaterial links to the precolonial ancestors and their culture. Worshipping the ancient Canarian heroes channels mainly through the traditional ways of popular expression –orality, ballads, folk songs…–, but their public recognition in the shape of statues and monuments spread over a number of the Islands settlements and their street maps is not less outstanding.

One of the few well-known islanders belonging to this period who unexpectedly still lacks an official monument or sculpture in his memory in despite of his great popularity in the collective imagination is Tanausu or Atanausu, chieftain or captain of the Acero party which was one of the twelve or thirteen political and territorial divisions on Benahoare island –La Palma as it was named by its first settlers– at the time of the Castilian conquest according to historian Brother Juan de Abreu Galindo –fl. c. 1590-1632– being also the last and only leader from La Palma putting up significant resistance to the occupation campaign launched between 1492 and 1493 by Castilian captain Alonso Fernández de Lugo.

Behenauco Peak (nowadays called Bejenado) which was a refuge to Tanausu during his conflict with his uncle Atogmatoma dominates the southern slope over Caldera de Taburiente’s huge crater with El Hierro island on the horizon. Famous recently formed Tajogaite volcano can be seen in the distance left to the peak crowned by evaporation clouds (source: PROYECTO TARHA).

Dividing Benahoare

Benahoarite petroglyphs at Belmaco Archaeological Park in the municipality of Villa de Mazo (La Palma) in the former territories of Tigalate party (source: PROYECTO TARHA).

Being Abreu Galindo the author most informed on the customs and history of La Palma’s ancient inhabitants he tells in his History of the Conquest of the Seven Isles of Gran Canaria[1]ABREU GALINDO (1848), book III, chapter V that the benahoarite chieftains being all of the same kin as can be expected from a society constricted by unappealable geographic limits used to make war among them not for the sake of their estates but for personal quarrels and that was the case of Atogmatoma, the chieftain of the Tijarafe party –the largest and most populated territory in the island– and his nephew Tanausu.

Due to some emmity of unknown origins one day Atogmatoma tried to attack Acero’s territories inside Caldera de Taburiente with 200 warriors penetrating the boundaries of Adirane –nowadays Los Llanos de Aridane– but being Tanausu warned the latter repelled the agression at the entrance of the crater which because of its orography it is easily defendable. In the wake of this first failure Atogmatoma invoked help from the parties of Tagalgen –the present municipality of Garafía– and Tagaragre –Barlovento– and then resumed his assault on Acero forcing his nephew to withdraw towards another strongpoint inside the crater. But Tanausu in view of his uncle receiving new reinforcements every day determined to look for help from Behenauco Peak –nowadays Bejenado– reaching his cousins Chenauca and Tamanca of Guehebey party, Aganeye of Adirane, Asuquahe of Ahenguareme and both Juguiro and Garehagua of Tigalate.

While Atogmatoma’s warriors prepared themselves to climb the mountain to get Tanausu an advance party sent by Chenauca came to Acero’s chieftain informing the majority of the helping force were on their way and so Tanausu decided to leave Behenauco down the outside slope of the crater towards Adirane plains to join his allies. But knowing Atogmatoma the intention of his nephew he commanded to intercept the first reinforcements leaded by Aganeye causing them to flee and captivating the latter’s father. In the wake of the mishap Aganeye and his brother Asuquahe fiercely retaliated killing and injuring many of their enemies and rescueing their father yet at the expense of Aganeye being seriously wounded during the brawl.

The next day Atogmatoma’s warriors and Tanausu’s confederates engaged in a decisive clash resulting in the defeat of the former who had to flee back to his land chased by Chenauca who spared his life thanks to the mediation of a daughter of Atogmatoma. To avoid the confederates’ reprisal and keep the peace Atogmatoma decided to arrange a marriage between his daughter Tinabuna and Aganeye.

A conquest «by objectives»

Probably a true portrait of Captain Alonso Fernández de Lugo by the time he was already appointed as “Adelantado” of the Isles of Canaria, as shown in the entailed estate document established by him in 1512 for his son Pedro Fernández de Lugo (source: Historical Provincial Archive of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Historical Section of Notarial Protocols, number 1,510, f. 1r).

The narrative sources agree on saying that with the War of Canaria at its turning point the project of conquering La Palma to expand the territories of the Castilian Crown had already been included in the plans made by Juan Rejón, the discharged first captain of the former campaign, but his open emmity towards the Herrera-Peraza family –who own four islands by then– and his particular spite towards Fernán Peraza the Younger, Lord of La Gomera, were paid with his own life during the stopover he made at this island while commanding the expedition presumably sent to begin the occupation of Benahoare. It took almost one decade since the end of the Gran Canaria campaign for another veteran seasoned in it, Captain Alonso Fernández de Lugo, to turn the Beautiful Island into the next target of his political and chrematistic ambitions.

The first obstacle Alonso de Lugo would face was the scarce interest of the Catholic Monarchs in conquering the islands still free –La Palma and Tenerife– in contrast to the urgency they showed orchestrating the occupation of Gran Canaria in 1478 since the objective pursued on that occasion was to set a base of operations well supplied with natural resources to put a stop to the expansion of the Kingdom of Portugal across the African Atlantic specifically the Guinea Gulf and the so-called Mine, a strategy whose completion could not be guaranteed from the islands under control of the seigneury of doña Inés Peraza who barely dissimulated her liking for the Portuguese just like the Royal Chronichler Alfonso de Palencia testified so eloquently:

[Inés Peraza] a long time ago had opposed [to the royal conquest of Gran Canaria] claiming this island’s property belonged to her so being dispossessed of it she shall not consent anyone to take it over but the mighty hand of a king and that she would rather the Portuguese to occupy it in the future, […][2]LÓPEZ DE TORO (1970), book XXXII, chapter III. This English translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

By means of the Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo signed in 1479 at the end of the Succession War to the Castilian Throne fought by both kingdoms after the passing of King Henry IV of Castile Portugal renounced to its sovereignty aspirations upon the Canaries in favor of Castile. Thus by the time Alonso de Lugo exposed his project to the monarchs occupying the two islands still free from the Castilian power had ceased to be a matter of prioritary interest when compared to other plans regarded as more urgent such as putting an end to the Nasrid Emirate of Granada –by then reduced to just a sort of a puppet kingdom belonging to Castile– or financing the first exploratory project by Genoese Christopher Columbus.

That is why in the case of the Conquest of La Palma the Catholic Monarchs decided to be Alonso de Lugo himself who met the expenses on his own but offering him an incentive of 700,000 maravedis should he was able to finish the occupation in the due date of one year starting from 1st October 1492.[3]MIRANDA CALDERÍN (2016), pp. 5-6, 10-11 To make things easier for him the Crown exempted its Captain from paying the so-called quinto real (Royal Fifth); that is, the fifth part of the prices he would be paid when selling the slaves he would capture on La Palma. This way Lugo could try in the short run to pay off the loans from his immediate financiers: Florentine Merchantman Giannotto Berardi –Christopher Columbus’ guarantor as well– and Genoese Francesco de Rivarolo.

Conquest or possession taking? The role of Francisca de Gasmira

A group of caves and a cavehouse in the area formerly known as Cuevas de Herrera in the territories of the Gasmira Benahoarite party next to the lower side of the Pass of Adamancasis (source: PROYECTO TARHA).

Alonso Fernández de Lugo landed at Tazacorte, a natural harbour under control of the Adirane party on 29th September 1492 where he placed his royal camp. Marching southwards right after with promises to protect and respect their possessions he quickly achieved to subdue all of the West parties with none of them opposing any kind of resistance as according to Abreu Galindo all of them had already negotiated some peace agreements with the settlers of El Hierro island in order to not keep on suffering their slaving raids.

Nevertheless, some public documents show that Alonso de Lugo arrived to La Palma with his job almost done, as four months before the landing a woman belonging to Gasmira party –a thirteenth faction not mentioned by Abreu Galindo, being Cuevas de Herrera a part of its territory– had met some chieftains in La Palma persuading some of them to join the Castilian cause and help Lugo with his campaign. And in view of these facts Professors Dominik Josef Wölfel and Antonio Rumeu de Armas understood that Lugo’s was not as much a conquest campaign as one to occupy the territories already supportive of the Castilian.[4]WÖLFEL (1930), pp. 1028-1029; RUMEU DE ARMAS (1969), p. 84.

Indeed Francisca de La Palma, also known as Francisca de Gasmira, a La Palma-born woman residing in Gran Canaria as a housekeeper to councillor Diego de Zurita, had been sent to her home island on board a caravel by order of Governor Francisco de Maldonado to met certain La Palma leaders at their request. This is how witness Pedro de Valdés recalled the facts on April 1506:[5]Adapted and translated from Old Castilian by PROYECTO TARHA.

[…] when the royal camp was by Granada, before the Adelantado came as Captain of La Palma, being Francisco Maldonado Governor of the isle of Gran Canaria and Bachelor Pedro de Valdés uncle of this witness Vicar-General of the said isle, […] that the said Governor and Vicar-General agreed to send La Palma-born Francisca who was a housekeeper to Diego de Zurita, a councillor of Gran Canaria, to La Palma isle on a caravel of Martín Cota to talk to the chieftains and principals of the parties on the said isle for they had sent to say they wanted to be Christians and surrender themselves to the dominance of Their Highnesses, and the said Governor and Vicar-General spoke on this matter with the lords of the [cathedral] council and all of them unanimously sent the said Francisca on the said caravel and paid six thousand maravedis of freightage out of the Chapter and Bishopry Table and the said Francisca went to the said isle and she brought with her to Gran Canaria four or five chieftains and most principals of the said isle and turned them Christians and baptised them in the said church and dressed them and that the said Vicar-General, uncle of this witness, dressed one of them and that this witness guesses that one of those chieftains died in Gran Canaria and after being Christians the said Francisca sent them back on the same caravel which brought them to the said isle of La Palma for them [to make] those of their parties turned themselves Christians. […] and after that [since then] to four months later more or less the Adelantado came appointed as Governor and Captain of the said isle of La Palma and then he took the isle of La Palma.[6]SERRA et al. (1953), pp. 93-94.

But in February 1495 the Catholic Monarchs repeated what Francisca herself had declared before the Crown following her own interest as well but she was just more restrained when it came to her mission’s success:[7]Adapted and translated from Old Castilian by PROYECTO TARHA.

[…] Francisca de La Palma, Canarian, resident on the said isle of La Palma [told] that she by order of Francisco Maldonado our Inquirer on the said isle of Gran Canaria and the other councillors on it went to the said isle of La Palma and contracted so much with the Canarians from it to the point she agreed with two parties in the said isle to be at peace and at our service and command; and that at the time Alonso de Lugo by our order went to conquest the said isle the said Canarians of the said two parties joined him and helped him to make the said conquest[…] and so, being the isle just conquered, the Canarians of one of the said two parties turned into Christians, […] and yet many of the said Canarians of the other party turned into Christians as well; […][8]RUMEU DE ARMAS (1969), pp. 310-311

With these precedents Lugo found resistance by Tigalate party only which he defeated with relative ease, killing some of its members, captivating many and fleeing others to take shelter on the mountainsides where they stood against whoever tried to get them. After beating those of Tigalate Lugo would find no other opposition to his occupation campaign than that of Acero party and its leader Tanausu in the selfsame heart of the isle: Taburiente crater.

By treason

The descent along the Pass of Adamancasis through the pine forest of Tenisca Ravine, one of the two major access ways (along Las Angustias Ravine) to nowadays National Park of Caldera de Taburiente, the path followed by Tanausu and his own towards their fateful meeting with Alonso Fernández de Lugo (source: PROYECTO TARHA).

After subdueing the rest of La Palma parties Alonso Fernández de Lugo attempted to attack Acero party entering Taburiente across the Pass of Adamancasis –La Cumbrecita– and even when he succeeded in making Tanausu to withdraw the latter moved to a higher ground impossible to take by the Castilians.

Lugo tried a new attack this time from the Pass of Ajerjo much harder to access for him and his men to the point he himself had to be carried upon the shoulders of his La Palma allies across a stretch. This pass which was supposedly less guarded by Acero took the Castilian near the refuge of Tanausu and his people who repelled the aggression again but paying the price of great affliction for the elder, children and women who suffered the harshness of the heights cold and that is why this hideout was then named Ayssuragan, “The place where they froze”.

In view of this unbowed resistance Alonso de Lugo sent his guide, a relative to Tanausu Christianized as Juan de La Palma, to parlay with the chieftain and his people promising to treat them well and leaving them in their lands if they would surrender to the Castilians, receive the Baptism and recognize the authority of the Catholic Monarchs. Tanausu replied he shall meet Lugo the next day –3rd May 1493– in Adirane, by Fuente del Pino.

Abreu Galindo narrates that Lugo asked his pathfinder whether he could trust Tanausu and as the guide replied so reassuringly he decided to trust none of them and ordered to lay an ambush on the Acero’s chieftain at the Pass of Adamancasis in case the latter tried to flee back to his refuge. Ugranfir, a relative accompanying Tanausu and his own along their descent to the meeting, recommended him to think twice because the enemy’s formation did not seem “to bring signs of peace” but Tanausu replied he shall go on forward as Lugo had given his word to parlay safe. But upon seeing the Acero people arrive the Castilian gave the attack sign to his army who after a tight battle defeated the Benahoarites and captured Tanausu who reproached Lugo for not keeping his word.

Another version, the one shared by Baroque Historians Tomás Marín de Cubas and Pedro Agustín del Castillo y Ruiz de Vergara narrates that Tanausu’s warriors at the look of the number and weaponry of the Castilians and their allies decided to continue not their descent towards Fuente del Pino and that watching them stop Lugo set off waging war to get them. Later with Tanausu in Lugo’s hands both captains blamed each other for what had happened and keeping not their promises. In any case, not being possible at present to certify the veracity of these accounts but given the behavior that Lugo would show later in a number of events it seems reasonable to suppose the conqueror had no intention at all to negotiate with his adversary, less to lose the opportunity to take him: he probably had decided to act like he did beforehand irrespective of what Tanausu would had done.

Vacaguare! : A legendary ending

Narrative sources taking care of Tanausu’s death –Abreu Galindo, Marín de Cubas and Castillo y Ruiz de Vergara– agree on that Acero’s leader starved himself to death when he saw himself as Lugo’s war captive who wanted to send him to Castile though they do not clearly specify whether his death happened during the deportation voyage as it seems most likely or ashore either on the island or at destination. In any case it is conceivable the warrior’s physical condition would not be at its best after the shortages due to the Castilian siege and this could explain the insinuation of relative speed in his passing that impregnates the accounts:[9]These translations by PROYECTO TARHA.

[…] among the captivated prisoners he [Lugo] sent one was Captain Tanausu who when seeing himself as a captive and being sent to Spain he got sick with his rage and let himself die eating not a single thing, which is a very common and ordinary thing for La Palma people to let themselves die.[10]ABREU GALINDO (1848), book III, chapter VIII, p. 189.

[…] and wanting to send to Spain to Their Highnesses the prisoner Tanausu with others from La Palma so much melancholy came to him he did not want to eat by no means and hastily he died.[11]MARÍN DE CUBAS (2021), book II, chapter XIII, p. 309.

[…] wanting [Lugo] to give notice to Their Highnesses and to send Tanauzu to them with others from La Palma so much melancholy came to them that without remedy of not wanting to eat Tanauzu let himself die and another two […][12]MARÍN DE CUBAS (1986), book II, chapter XV, p. 238.

This unexpected assault was so sensitive for Tanausu and of such sadness that his days were so lacking with life neither rising his eyes nor eating while he had it until die.[13]CASTILLO Y RUIZ DE VERGARA (1848), book II, chapter XXVII, p. 161.

Tanausu’s shocking decision whose memory for sure had to root in the first post-conquest tradition ended up permeating modern popular culture leaving its most known impression on the long-held belief that the warrior had declared his intention to renounce his own life crying out Vacaguaré!, an expression supposedly meaning “I want to die”. However, in known ancient written sources there is no testimony supporting the reality of this claim. Indeed, the expression vacaguare firstly picked by Abreu Galindo indicates specifically that when some La Palma-born person felt sick he expressed this way to his kin his desire to die and then they would shut him up in a cave to fulfill this last will leaving just a bed made of leather and a ganigo —a large jar– filled with milk:

At sickness these people were so gloomy, on being sick they would tell their kin vacaguare, “I want to die”. Then they would fill a vase with milk and put him into a cave where they wanted to die and would make a bed of leather for him where he would lay and put the ganigo with milk by the bedhead and shut the entrance of the cave where they would leave him to die.[14]ABREU GALINDO (1848), book III, chapter IV, p. 176.

The Ballad of Tanausú and Acerina

To solve the origin of this belief we must date back to a travel book published in 1862 by La Palma-born Professor Benigno Carballo Wangüemert (Los Llanos, 1826 – Madrid, 1864): Las Afortunadas – Viaje descriptivo a las Islas Canarias —The Fortunate — A Descriptive Voyage to the Canary Islands–.

In chapter XII,[15]CARBALLO, chapter XII, pp. 251-253 Don Benigno tells how during a guided trek to Caldera de Taburiente that he had organized to regale a visitor the group met two young shepherds to whom they invited to lunch and how they sung a ballad in appreciation. In the ballad, Tenacen, the last «Guanche King of La Caldera» and Mayantigot, «King of Adirame» fight for the love of a woman called Acerina –a name that Professor Juan Álvarez Delgado supposed as being later imagined upon that of Acero party–,[16]DÍAZ ALAYÓN et al. (2014), p. 16. a struggle they try to resolve in succesive competitions without anyone prevailing upon the other. At last is Acerina herself who asks both suitors to quit their fighting saying that she will be the one to choose on the Taburiente Plateau who of them shall get her love having the loser to accept the unappealable decision. Finally Acerina chooses Tenacen by means of resting her hand upon his shoulder and Mayantigot accepts his defeat and withdraws to cry his loss in solitude.

Shortly after, another La Palma-born gentleman, journalist, professor and philanthropist Antonio Rodríguez López (Santa Cruz de La Palma, 1836-1901) freely adapted and extended this folk ballad in a little novel of historical fiction he published next year (1863) by installments in El Time newspaper under the title Vacaguaré! (Quiero morir!) Leyenda palmera —Vacaguaré! (I want to die!) A Legend from La Palma–, being probably him who firstly put the accute accent both to this tragic expression and to the name of the Benahoarite warrior, having these forms quickly popularized and even permeating historiographical works chronologically closer to the publication.

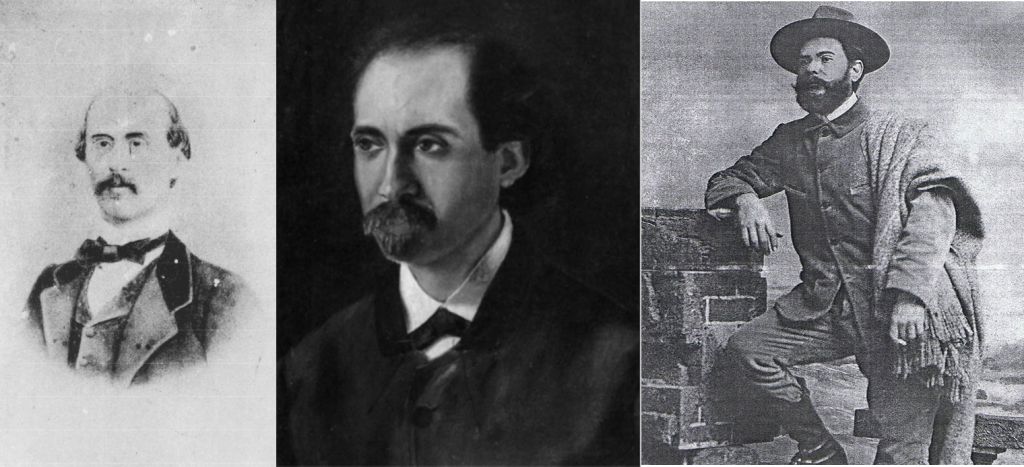

Left to right: Professors Benigno Carballo Wangüemert and Antonio Rodríguez López, and journalist and politician Secundino Delgado Rodríguez introduced Tanausu character into Canarian modern popular culture (sources: Memoria Digital de Canarias / Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos / Círculo de Bellas Artes de Tenerife : José Pérez Vidal / Víctor J. Hernández Correa / Manuel Hernández González).

This work follows the line of the Canarian indigenist movement set by scholars like Tenerife-born Manuel de Ossuna y Saviñón (San Cristóbal de La Laguna, 1809-1846) with his work Los guanches o La destrucción de las monarquías de Tenerife —The Guanches or The Destruction of the Monarchies of Tenerife— (1837) or Grandcanarian Agustín Millares Torres (Las Palmas, 1826-1896) with his novel Benartemi, leyenda canaria —Benartemi, a Canarian Legend— (1858) later re-entitled El último de los canarios —The Last of the Canarians— (1875), a tendency that would find its reflex on political grounds at the very beginning of the 20th century when journalist and politician Secundino Delgado Rodríguez (Santa Cruz de Tenerife, 1867-1912), one of the fathers of Canarian nationalism, adopted Rodríguez López’s novel title as well as the latter’s own name as a pen-name to publish in 1904 his autobiography ¡Vacaguaré…! (Vía-Crucis), an expression adorning also the front page of the short-lived autonomist newspaper founded by him in 1902.

Thus the idea of linking the vacaguare expression to Tanausu’s voluntary death probably came out of Rodríguez López’s imagination, who joins both Abreu Galindo’s lines in one single passage of chapter VII in his story, a literary license whose popular prevalence has had the undeniable merit of bringing back to life in our time –paradoxically contradicting not only the historiographical testimony but the warrior’s own will also–, the soul of the last hero of Benahoare:

Tanausú was made prisoner and uttering the terrible phrase: Vacaguaré!, he sealed his lip and lowered his eyes.

We hope one fine and not distant day a statue of Tanausu and a plaque explaining the events we have just recalled will preside –this is what we propose– the so-much visited viewpoint of Adamancasis –La Cumbrecita– for we Canarians and foreign people could admire much more than the undeniable natural and scenic values of the site.

Antonio M. López Alonso

A partial view of Caldera de Taburiente, territory of the Acero party, from La Cumbrecita viewpoint, formerly the Pass of Adamancasis, a much-visited site of tourist interest that we propose as a place to erect a monument dedicated to the memory of Tanausu (source: PROYECTO TARHA).

References

- Abreu Galindo, Fr. J. de (1848). Historia de la conquista de las siete islas de Gran Canaria. Escrita por el Reverendo Padre Fray Juan de Abreu Galindo del Orden del Patriarca San Francisco, hijo de la provincia de Andalucía. Año de 1632.. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Imprenta, Lithografía y Librería Isleña.

- Arias Marín de Cubas, T. (1986). Historia de las siete islas de Canaria. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Real Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País de Gran Canaria.

- Carballo Wangüemert, B. (1862). Las Afortunadas : Viaje descriptivo a las Islas Canarias : Por D. Benigno Carballo Wangüemert : Catedrático de Economía Política : en la Escuela de Comercio y en el Real Instituto Industrial de Madrid; […]. 1.er grupo. (Tenerife, Palma, Gomera, Hierro.). Madrid: Imprenta de Manuel Galiano

- Castillo y Ruiz de Vergara, P. A. del (1848). Descripción histórica y geográfica de las islas de Canaria. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Imprenta Isleña.

- López de Toro, J. (1970). “La conquista de Gran Canaria en la “Cuarta Década” del cronista Alonso de Palencia. 1478-1480″, Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos, vol. 1, núm. 16, pp. 325-393. Cabildo de Gran Canaria.

- Marín de Cubas, T. (2021). Conquista de las Siete Yslas de Canaria (1687) : Tomás Marín de Cubas : Edición crítica de Antonio M. López Alonso. La Orotava – Santa Cruz de Tenerife: LeCanarien ediciones.

- Miranda Calderín, S. (2016). “Diferencias entre las primigenias exenciones fiscales que disfrutaron las islas realengas canarias en el siglo XV”, Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos, vol. 1, núm. 62, pp. 1-21. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Cabildo de Gran Canaria.

- Rumeu de Armas, A. (1969). La política indigenista de Isabel la Católica. Valladolid (España): Instituto “Isabel la Católica” de Historia Eclesiástica.

- Serra, E.; Rosa, L. de la (1953). Reformación del repartimiento de Tenerife en 1506 y colección de documentos sobre el Adelantado y su gobierno. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Instituto de Estudios Canarios – Cabildo Insular de Tenerife.