An idealized effigy of Captain Juan Rejón, military commander of the expedition to invade Gran Canaria ordered by the Catholic Monarchs, on a commemorative plaque located in Vegueta neighborhood, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, year 2018. (source: PROYECTO TARHA).

(This post has been extended with a fourth document, 11th December 2022)

By their nature, armed conflicts have always been a destination and a departure point at the same time. A departure point for those who are forced by violence to suffer the physical, cultural and emotional uprooting that fleeing from a war zone entails. A destination for those who see in the chaos of the conflict an opportunity to escape punishment, reprisals and persecution ordered by the established power or at the design of third parties, either for political or personal reasons, or because the fugitive actually exercised criminal violence against people or assets. In the latter case, war dresses the offender with a cloak of impunity that allows him to continue committing, this time with no other restriction than his own will, those or other crimes and felonies.

An especially profitable case of twinning between delinquency and warmongering is the employ of convicts by political power as war troops in order to fulfill its own interests, freeing those been governed from the risk posed by the presence of the criminal and on the other hand channeling towards the war effort at zero cost the latent aggressiveness in the person or alternatively his will to survive a conflict that he may judge as alien to his interests.

On this matter, three out of the four public documents whose transcriptions we are presenting here are not unknown ones[1]We detail the appropriate references in the notes of the respective transcripts.. In fact they were listed in 1981 by Professor Eduardo Aznar Vallejo[2]AZNAR VALLEJO (1981), pp. 19, 26-27, 32., one of them was partially copied earlier by Professor Antonio Rumeu de Armas and at least two of them have subsequently been the subject of discreet publications, although one of them is incomplete. We now intend to make them known in their entirety along with a fourth and to offer at the same time a broader perspective on their context.

“Should the infidels be converted or thrown out of the island”

The Catholic Monarchs like other monarchs of Castile issued a number of letters of pardon during their reign in which they promised to grant amnesty to any criminals residing in certain parts of their domains in exchange for their voluntary service in certain wars for a stipulated minimum period of time, provided that the inmates ran with their own expenses.

The conquest of the Canary Islands –particularly that of the islands of Gran Canaria, Tenerife and La Palma– was not exempted from this policy: according to the first document that we transcribe (in Spanish), on December 10th, 1480 in the middle of the war against the first of these islands, Queen Isabel I of Castile ordered a levy of convicts in the Cantabrian towns of Costa de la Mar –San Vicente de la Barquera, Santander, Laredo and Castro Urdiales– and neighboring regions, because –we modernize and translate the texts from Old Castilian–:

[…] the said island cannot thus be completely won over and reduced the said infidels on it to our holy faith without more people having to go and help those who are there yet, and observing how much Our Lord shall be served should the said infidels be converted to said our faith or thrown out of the said island […]

Consequently, the queen offered an amnesty to criminals from the region as long as they served for at least six months in the Gran Canaria campaign:

[…] having incurred various civil and criminal sentences and because at present I cannot be informed or truly know the quality of the said crimes it is my mercy and will that they be converted into the service that the said delinquents would render in the conquest of Gran Canaria serving each one by himself or with the people that should be agreed […] for a period of six months […]

A period whose compliance had to be certified in writing by the military leaders stationed on the island: Pedro de Vera –governor and captain– and Mikel de Moxica –recipient of the tribute called the Royal “Fifth”–.

As for forgivable crimes the Crown did not skimp on its permissiveness:

[…] all and any crimes and excesses and offenses and robberies and forces [sic, rapes] and deaths of men and any others that had been committed up to now including from the major to the minor case […]

Although, naturally, the tolerance of the Castilian throne towards the crimes perpetrated also had its limits:

[…] except any case of treason or crime of false money or falsehood made in the name of a king or queen or crime of taking money or gold or silver out of these my kingdoms, […]

The second document referring to these recruitments of criminals is even more interesting as it deals with Queen Isabel I’s response to a request to the Crown presented by a prisoner –Gonzalo Fernández (Ferrández) Mansino, a resident of the Galician town of Noia– to have the amnesty won for the services rendered in the Conquest of Gran Canaria confirmed, since the local authorities did not respect it.

Copies of other public documents are included in this Royal Provision among which is another offer of amnesty ordered by the Queen on January 17th, 1481, this time addressed to the convicts of the Kingdom of Galicia in which to the previous list of condonable crimes are added those of road robbery and church and monastery breaking. Curiously, this time the destination of the reinforcements is the conquest of La Palma and Tenerife, whose invasion as it is known did not begin until 1492 and 1494 respectively. Therefore, we guess that this early attempt to occupy these two islands is identifiable with the entrustment of the mission to Captain Juan Rejón, deposed military commander of the Gran Canaria campaign, who had been sent prisoner to the court in the second half of 1480 by Governor Pedro de Vera to answer for the irregular summary trial and execution of Governor Pedro de la Algaba.

It is also striking that in this amnesty offer, which was issued just 37 days after the previous one, and in which it was said that Gran Canaria could not be completely conquered without the assistance of reinforcements, the Queen asserted that the island is already under control:

[…] the isle of Gran Canaria […] by the grace of Our Lord was won and the infidels on it were converted to our Holy Catholic Faith […]

This may be related to the killing of the chieftain Doramas at the hands of Pedro de Vera and his men and to a supposed first “surrender” of the island that on May 30th was echoed in the so-called Letter of Calatayud, although the war would not be terminated until at least two years later.

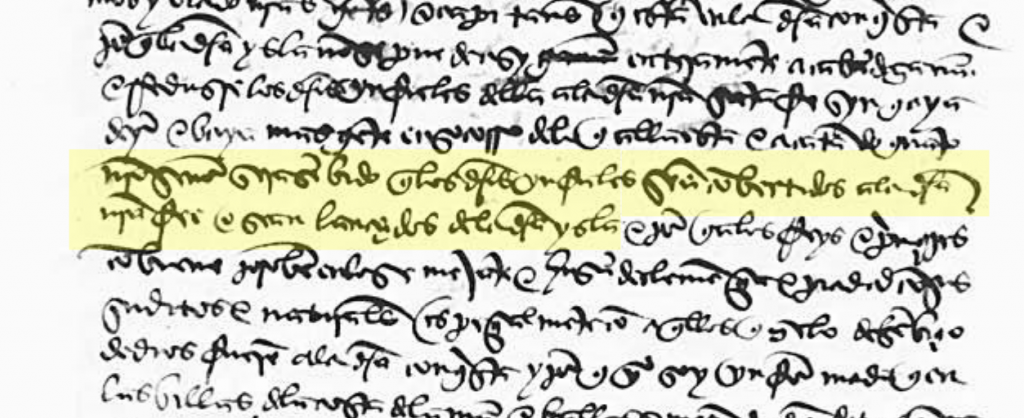

“Our Lord shall be served should the said infidels be converted to said our faith or thrown out of the said island” (source: Archivo General de Simancas, catalogue number RGS,LEG,148012,50, f. 1r).

The foundation of an ancient legend?

The interest of the manuscript does not end here: Fernández Mansino –accused of killing a woman, Inés de Lema– declares that he was ordered to serve eight months in Gran Canaria along with nine other murderers: Gonzalo Marinón, Ruy Cato, Entor (Héctor? ) González, Gonzalo Muñoz, Juan de Santa Marta, Velasco Pérez, Alfonso de Campana, Fernando de Cachón and Gómez Sobrón. And the convict recounts that on arriving in the Canary Islands near Lanzarote they were trapped in a strong storm from which they came out alive in extremis at the cost of losing the supplies and weapons that the ship was carrying, a complication that would be repeated on a second voyage although this time they managed to reach port in Sanlúcar de Barrameda:

[…] keeping on their voyage to said Canaria and going onwards across the sea near the said island of Lanzarote such a great fortune [sic, tempest, storm] arose in the said sea that they had to lose and indeed lost all the provisions and supplies and weapons they were carrying on the said ship and that they would have perished unless Our Lord God miraculously wanted to save them, and then on the run again to the said island of Gran Canaria another storm came upon them and sent them to the port of Sanlúcar so that they they had to return and returned from the said voyage […]

These events remind us of an old legend that in Gran Canaria attributes the founding of the missing chapel of Santiago el del Pinar or El Chico -St. James the Lesser, Morro de Santiago, in what is at present the municipality of San Bartolomé de Tirajana- supposedly to some Galician sailors who were said to have built it in gratitude for having survived a heavy storm[3]SANTIAGO CAZORLA (2000), pp. 43-44, 49-50..

Lastly the third and fourth documents although unpublished -this we believe- are of no great interest as they only contain respectively a protest of one Alfonso Rodríguez, a resident in the Galician city of Santiago, to achieve that the royal pardon granted by Queen Isabel to the murderers in Galicia in exchange for the aforementioned service in the War of Canaria would be respected in his case and another one named Gonzalo Carrillo «the Younger» a resident in Pontevedra who also requests to be excused from serving in the war “against the moors” for he had already won the royal pardon at the War of Canaria.

The historical context

It is tempting to think that the issuance of these letters of pardon was a resort habitually used during the conquest of the Canary Islands, perhaps extended to a wider territorial scope spanning all the domains of Castile although as we say there are more amnesty documents issued in reference to other war campaigns all of them similar when it comes to procedure and both preceding and following the three we present here.

Nevertheless it seems that the recruitment of criminals in Galician and Cantabrian towns had an eminently political and strategic purpose since these were regions seriously affected by severe social conflict of a structural nature where the old feudal model of land ownership was still rampant in open opposition to the attempts of the Castilian Crown to subdue families and local noble groups in conflict with each other and which in turn exercised unbearably abusive practices on the people and the peasantry. Tensions that occasionally exploded in large riots –an issue extensively studied by Professor Carlos Barros Guimerans–, such as the so-called Great Irmandiña War (1467-1469) which took place in Galicia during the reign of Henry IV of Castile, and so called because of the participation against part of the noblemen and high land-owning clergy of the Galician council brotherhoods among the various constituted and promoted as people militias mainly in charge of police duties but which were useful for the Trastamara monarchs as paramilitary forces to exercise coercive control on the rebellious nobility, as evidenced by the number of fortresses and strongholds destroyed by the irmandiños across the Galician countryside.

In the case of the War of Canaria where members of the recently created Andalusian Hermandad -Brotherhood- would have a leading role under the command of Juan Rejón –representative in Seville of the General Holy Brotherhood– sending convicts from those towns would not only have a “depressurizing” purpose: possibly it would serve as an exemplary lesson to some of the most problematic landowners.

In this regard we have found in public documentation an evidence that we believe unpublished showing the participation by royal order of one of these conflicting nobles in the conquest of Gran Canaria; a character already mentioned by some insular narrative sources but of whose intervention in the campaign we had no official evidence until now. A name and a proof that we will present in a future post.

Bibliography

- Aznar Vallejo, E. (1981). Documentos canarios en el Registro del Sello (1476-1517). La Laguna – Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Instituto de Estudios Canarios – Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

- Cazorla León, S. (2000). Los Tirajanas de Gran Canaria. Notas y documentos para su historia. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Ayuntamiento de San Bartolomé de Tirajana.

- Rumeu de Armas, A. (1975). La conquista de Tenerife. 1494-1496. Madrid: Aula de Cultura de Tenerife