The idealised statues of Guise and Ayose, a work by Lanzarote-born sculptor Emiliano Hernández García, standing on the namesake viewpoint in the municipality of Betancuria in Fuerteventura (source: Luc. T / Wikimedia Commons).

In honor of my father’s family: my great-grandfather Matías Casanova “El Charco”, my grandmother, Susana Casanova Darias, and my great-aunt Manolita. From Vega de Tetir. “From Guise’s side.”

That Guise and Ayose were the names of the two maho chieftains who ruled Fuerteventura island at the time of the conquest by Jehan de Béthencourt and Gadifer de La Salle is something well known in Canarian popular culture. Such is so that the latter has been a relatively frequent anthroponym imposed among males born in the Canary Islands since the mid-1970s, a time when recognition and homage to precolonial cultural and historical roots began to be claimed with some force after being silenced for a long time.

But a much less known fact is that both names survived the European conquest for four centuries without losing an iota of their everyday nature. And even more surprising is that they did not do it in the field of toponymy, a common refuge for forgotten words, but in a very unusual way: the administrative field.

In the narrative sources

None of the two known versions of Le Canarien, the chronicle that narrates the conquest campaign launched by Béthencourt and La Salle in the Canaries, mention any of these two anthroponyms in despite of doing it with the Christian names that were imposed to both chieftains at the time of their baptism, an account that appears only in the version attributed to Béthencourt’s heirs:

Firstly came before the Lord of Béthencourt one of the kings, the one of the side facing Lanzarote island, […] and he was baptised along with the people he had brought with him on 18th January 1405, receiving the name of Louis. […] On 25th January went before the said Lord the king who resided in the side facing Gran Canaria with forty-six of his people but they were not baptised that day but after three instead and the name Alphonse was imposed to this king.[1]AZNAR et al. (2006), p. 250.

Another part of the chronicle witnesses the rivalry between both chieftains:

What is true is that in that isle of Erbane there are two kings that have been at war for a long time, in which they had have many dead many times in such a way they are very weakened now. And as we said before in another chapter it is obvious war have been between them as they own the strongest castles built their own way to be found nowhere else; they have also towards the inner parts of the island a great stone wall spanning in that place the whole land going across from one shore to the other.[2]AZNAR et al. (2006), p. 248.

Arguings that both of them took aside at least before the new, self-imposed lord of their island when he bestowed them some properties in Lanzarote:

They came in the presence of the Lord of Béthencourt the two kings of the island of Fuerteventura that have been baptised and he bestowed them estates and lands as well just as they asked him awarding each of them four hundred acres of trees and lands, […][3]AZNAR et al. (2006), p. 265.

Resuming the core theme of our article, the first known reference to autochtonous names Guise and Ayose appears by the pen of Andalusian friar Juan de Abreu Galindo, who finished his one and only known historiographical opus in 1632 though most of his data refer to the second half of 16th century. In chapter XI of book I of his History of the Conquest of the Seven Ysles of Canaria he asserted:

This isle of Fuerteventura was divided in two kingdoms, one from where Villa is to Jandía and its wall; and the king of this side was named Ayoze; and the other one from Villa to Corralejo and this one was named Guize. And these two estates were splitted by a stone wall going from one sea to the other sea, four leagues.[4]ABREU GALINDO (1848 [1632]), [Book I, Ch. XI], p. 33.

And in chapter XIII:

There were dissenssion and arguing between the two kings of this isle of Fuerteventura about pastures between kings Yose and Guize.[5]ABREU GALINDO (1848 [1632]), [Book I, Ch. XIII], p. 37.

On the forgotten “kingdoms”

We know nothing else about Guise and Ayose’s lives out of these scarce chronicle informations. But thanks to some surviving public documents we do know their names keep on alive and kicking in Fuerteventura at least until the 18th century. And that is because both of them named two of the three big regions or territories dividing the island administratively since the beginning of its eurocolonial stage.

We cannot claim either these areas matched the territorial domains of each chieftain during their lives only as could be inferred from Abreu Galindo’s testimony, or whether their naming existed before the lives of these personalities. In any case mentions of these names are a constant in Fuerteventura councils that took place between 1606 and 1774, specially when it comes to the yearly election of the so-called «regidor diputado» –representative councillor– or «cadañero» –literally, every-year person– of each side and also in public calls for doing gatherings of guanil –wild, non-marked– cattle as proved by council minutes luckily recovered and published between 1966 and 1970 as excerpts by judge Roberto Roldán Verdejo and graduate Candelaria Delgado González.

Let us see an example in the assembly held on 21st January 1615 in the hermit of Valle de Santa Inés:[6]ROLDÁN VERDEJO et al. (1970), p. 107.

They gathered after attending the main mass to elect the representative councillors and procurator. First the following persons were raffled: Andrés Perdomo de Vera, Francisco Perdomo Betancor, Juan Rodríguez Perdomo, Miguel Perdomo de Vera and Agustín Perdomo and Diego Viejo López, all of them for the Guise’s side, putting their names on little papers and leaving in another part the same quantity blank and one of them with the name «Councillor». For Ayose’s side they put on other little papers Juan Perdomo Francés, Francisco de Morales Ortega, Luis Perdomo de Vera, Juan de Senabria Marichal, Marcos Luzardo Cardona, Sebastián Hernández Soto, Melchor Enríquez, Gaspar Fernández Peña and Felipe de Santiago with other blank ones and one of them reading «Representative councillor for Ayose’s side». After putting them inside two hats two kids took them out and came out for Guise Diego Viejo López and for Ayose’s, Melchor Enríquez.

Which was the border or limit of these two areas? According to the minutes of the assembly held on 20th February 1612 at Santa María de Betancuria:[7]ROLDÁN VERDEJO et al. (1970), p. 93.

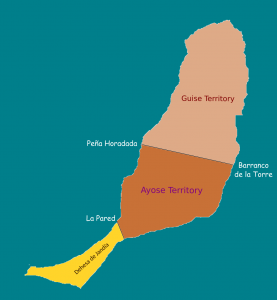

As wild donkeys are loose due to not having gathered them the neighbors mark them to say they are theirs causing harm to the people. They agree to mark none of them if the Council’s representatives are not present and neither to shoo them away. The said representative councillors are Lucas Melián Estasio and Juan Hernández Jerez and it is understood that Ayose and Guise are divided along from Barranco de la Torre to Peña Horadada […]

And according to the council held on 25th January 1616 at the same place:[8]ROLDÁN VERDEJO et al. (1970), p. 116.

It was agreed that attending to the fact that bovine cattles are loose on this island from which it results too much harm to cereal crops they ordered and commanded that all the neighbors from Ayose’s side, understanding it spans from the village of Cassillas [de Morales or del Ángel (?)] to the said side do gather and catch all bovine cattles in it […] And they also agreed that the neighbors from Guisse’s side […] do gather and catch all their bovine cattles […] in the pen of Esquén at the village of Chincoy, […]

According to the excerpt of the chronicle Le Canarien we cited above the border was demarcated by a long stone wall going «from one sea to the other sea», «four leagues» as Abreu Galindo specifies; this is to say about twenty kilometers which is roughly the width of Fuerteventura between the indicated geographical landmarks indeed. What is perhaps not so believable is that said wall –which should not have been very high, given its essentially delimiting function– spanned that entire distance, especially if we take into account the irregularity of the terrain, mountainous and even steep in sections so perhaps it would be necessary to think of a construction that only existed in segments, or maybe some work along a longer route to accommodate the most accessible layout of the orography. Be that as it may, this wall must no longer exist during the lifetime of the historian friar, who speaks of it in the past tense, while the French story tells of its presence at the time of the events it narrates.

To these two territories was added a third, referred to many times in a number of public documents: Dehesa –pasture land– de Jandía, which Abreu Galindo, in the cited text, refers to as being separated from the «kingdom» of Ayose by a «wall», a second wall, which was the one that presumably gave its name to the current place of La Pared –The Wall– and which is usually confused with its older “sister”, the real dividing line between the Guise and Ayose demarcations. This also missing line marked the northern limit of the stately preserve and meadow, which is already perfectly marked by the line of the field of jables –sands made either of volcanic material or seashells–.

Some of the minutes also name a fourth intermediate administrative division called Medianía or Medianías, implemented for management needs, and which precisely for this reason will not be the subject of this article.

Antonio M. López Alonso

References

- Abreu Galindo, Fr. J. de (1848 [1632]). Historia de la conquista de las siete islas de Gran Canaria. Escrita por el Reverendo Padre Fray Juan de Abreu Galindo del Orden del Patriarca San Francisco, hijo de la provincia de Andalucía. Año de 1632. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Imprenta, Lithografía y Librería Isleña.

- Aznar, E.; Corbella, D.; Pico, B.; Tejera, A. (2006). Le Canarien. Retrato de dos mundos. I. Textos. La Laguna: Instituto de Estudios Canarios.

- Quintana Andrés, P. C.; Camino Pérez, A.; Sánchez Romero, M. de la P. (2017). Litigio sobre la Dehesa de Jandía (1500-1815). Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Gobierno de Canarias : Archivo Histórico Provincial de Las Palmas.

- Roldán Verdejo, R.; Delgado González, C. (1970). Acuerdos del Cabildo de Fuerteventura. 1605-1659. La Laguna: Instituto de Estudios Canarios – Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.