The Essentials (X): The Accounts on the Conquest of Gran Canaria

In 1966, as a result of an investigation encouraged by Professor Antonio Rumeu de Armas, then doctoral student Miguel Ángel Ladero Quesada published in Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos the transcription of some surprising documents that shed new light on the royal conquest of the Canary Islands which at the same time raised new questions. This valuable information appeared in three expense accounts, a kind of document whose arid and routine nature does not invite to presage any interesting data. Nothing further from reality.

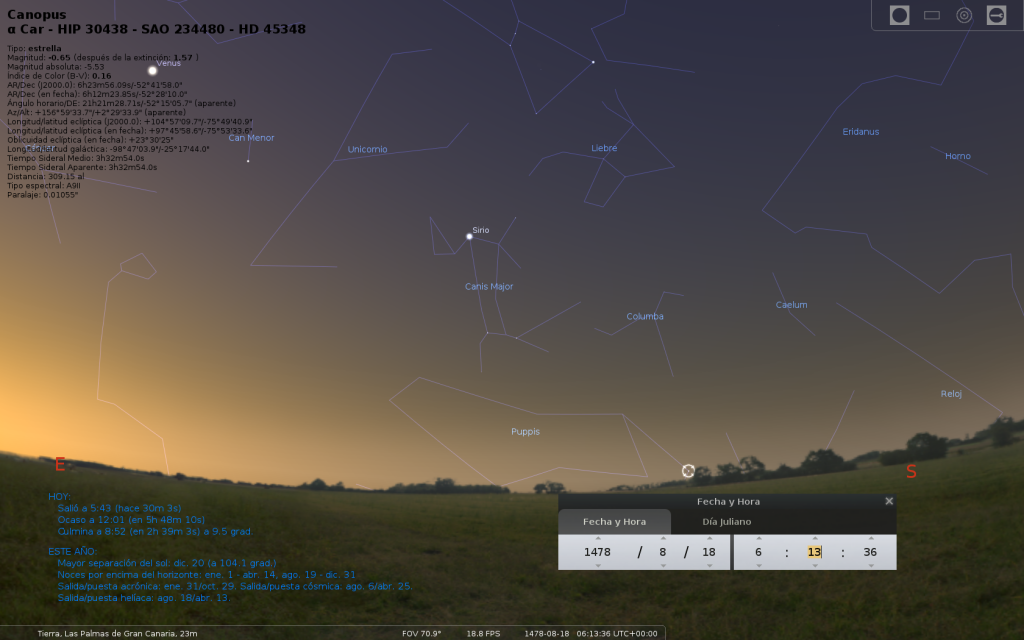

The first account, dated between 1481 and 1482, right in the middle of the conquest of Gran Canaria, was signed by Pedro de Arévalo, supplier of the conquering army. The second relation of expenses was signed by Juan de Frías, Governor of the Palace of Córdoba –not to be confused with his namesake Bishop of Rubicón–. Finally, the third account showed the rubric of Antonio de Arévalo, son of the former, designated payer of the Castilian hosts that participated in the War of Canaria after its ending.