In 1966, as a result of an investigation encouraged by Professor Antonio Rumeu de Armas, then doctoral student Miguel Ángel Ladero Quesada published in Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos the transcription of some surprising documents that shed new light on the royal conquest of the Canary Islands which at the same time raised new questions. This valuable information appeared in three expense accounts, a kind of document whose arid and routine nature does not invite to presage any interesting data. Nothing further from reality.

The first account, dated between 1481 and 1482, right in the middle of the conquest of Gran Canaria, was signed by Pedro de Arévalo, supplier of the conquering army. The second relation of expenses was signed by Juan de Frías, Governor of the Palace of Córdoba –not to be confused with his namesake Bishop of Rubicón–. Finally, the third account showed the rubric of Antonio de Arévalo, son of the former, designated payer of the Castilian hosts that participated in the War of Canaria after its ending.

Puerto de Las Nieves (Agaete, Gran Canaria) in 2015. In the distance, Mount Amagro, a sacred place to the ancient Canarians. On the right, Roque de Las Nieves. The Tower of Agaete was built at the foot of this geological landmark between July and September of 1481 (source: PROYECTO TARHA).

The three shipments and the Tower of Agaete

The account, or more precisely, the accounts presented by Pedro de Arévalo firstly detail the chartering of three shipments to land supplies and reinforcements in Gran Canaria.[1]LADERO (1966), pp. 21-41.

As determined by the economic policy prevailing in those years, chartered vessels did not belong to the Crown of Castile but were rented to individuals. Thus, the accounts reflect the chartering of three caravels, two naos, one ballener and another ship from different owners, and it is of special interest the descriptions related to these vessels, as well as the detail of the goods, provisions, weapons and tools they carried, plenty of technical, ethnographically valuable, vocabulary: for example, there are terms still used in the Canary Islands, as regatón –an old ferrule, now a metal point to shepherds’ staves– and sera –variant sereto, a sort of basket– and poses the problems of horse sea transport,[2]LADERO (1966, Pp. 24, 36). as well as the composition of the crews. For example:

- Caravel: one master, one boatswain, one pilot, three sailors, four cabin boys and one page.

- Nao: one master, one boatswain, one pilot, eleven sailors, eight cabin boys, two pages and one cook.

One of the most illuminating new data provided by this account is the dating of the building of the Tower of Agaete, the advance post that Castilians rose at current Puerto de Las Nieves, on the northwest coast of Gran Canaria. Governor Pedro de Vera took advantage of the first expedition’s landing, in which twenty-five reinforcement knights were led by Captain Pedro de Santisteban, to retain caravel Buenaventura between July and September of 1481 in order to help building the fortress.

Plate commemorating the stay of the Queen of Canaria in Córdoba (Spain). Work of sculptor Facundo Fierro, located in the Castle of the Christian Monarchs (source: Córdobapedia).

The enigmas of the anonymous guanarteme and the Queen of Canaria

The surprises contained in the accounts transcribed by Professor Ladero Quesada do not end here: the information provided by Pedro de Arévalo details the maintenance expenses, lodging and equipment of an anonymous guanarteme (Grandcanarian chieftain), accompanied by a retinue of Canarian knights who on May 1481 paid obedience to the Catholic Monarchs in the Aragonese town of Calatayud.

The identity of these characters remains as a mystery although several experts have debated long on the same, constituting one of the links yet to be recovered for Canarian historiography. We will comprehensively deal with this issue in an upcoming post devoted to the so-called Pact of Calatayud.

Another fact even more enigmatic is provided by the accounts of Governor Juan de Frías, who declared he was in charge of the Queen of Canaria, also an anonymous person, a woman who was entrusted to this royal servant by command of the Castilian monarchs that came to him sick to death and eight-months pregnant. This indigene woman survived her illness and gave birth to a girl in Córdoba on September 30th, 1482. A year later, in September 1483, Juan de Frías delivered this person to her husband, of whom he did not mention the name, so that they could return together to Gran Canaria.

This time, the identification of these characters, although not completely sure, does offer greater visions of success, the male probably corresponding to Tenesor Semidán, christianized as Fernando Guanarteme,[3]Or more probably, Guadnarteme, as is well documented in some other records. last acting leader in the ranks of Gáldar’s bloc, who voluntarily surrendered to the invaders, and his wife, the woman that an eighteenth-century genealogist, Brother Juan Suárez de Quintana, claims to have been originally called Abenchara Chambeneguer, baptized Ana Chambeneguer.[4]SUÁREZ (2006), p. 192. The neonate, one of the two known daughters of the couple, and the only European of birth, if we take as certain Professor Manuel Lobo Cabrera’s hypothesis, [5]LOBO (2011), p.55. was probably Catalina Hernández Guanarteme, settled in Gáldar and who died in Agüimes (Gran Canaria).

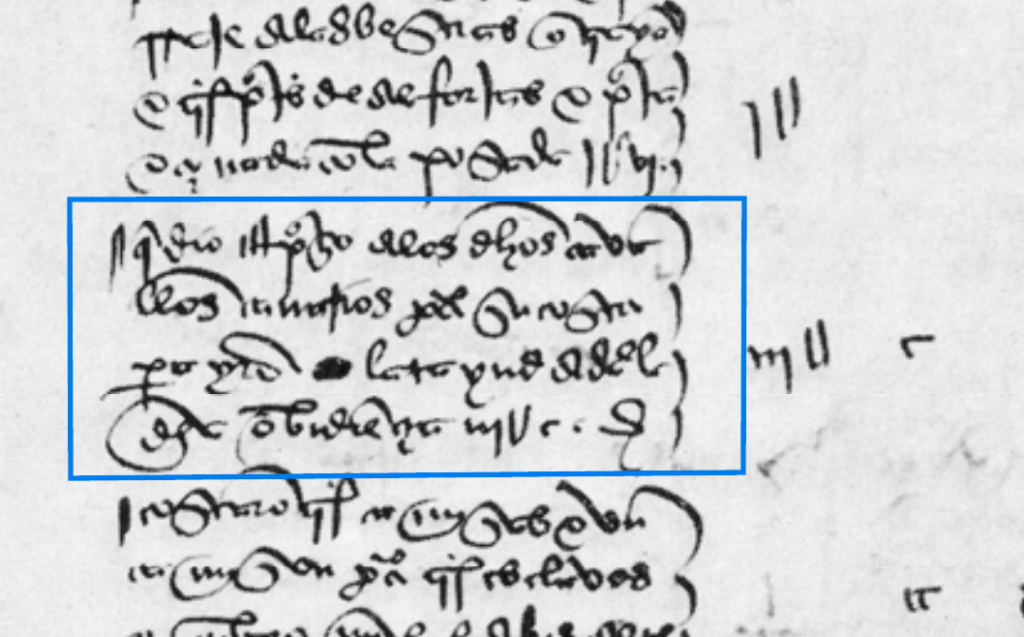

… that he gave and paid above said Canarian knights for their expenses for going to [Ca]latayud to give the above said obedience III M C [3,100 maravedis] (fuente: LADERO (1966), pp. 48-49. Translated and adapted from old Castilian by PROYECTO TARHA).

The rebels and the deported

The last of the accounts, justified by Antonio de Arévalo, breaks down, among others:

- Payments to pawns and knights who served in the conquest of Gran Canaria, almost always in a mixed way, in cash and in kind (cereals).

- Concession of the Royal Fifth’s half to Pedro de Vera on all the captures he eventually take on Gran Canaria, Tenerife, La Palma and in Barbary.

- Appraisal of captives from La Palma and Tenerife enslaved between 1484 and 1485.

Attention is drawn to two breakdowns in particular:

- An appraisal of slaves arrested during a raid against Grandcanarian rebels in 1485, which also captured two tenerifes –note this ethnonym replaces the usual guanches or Canarians from Tenerife– that had escaped their masters to join the uprising.

- The refusal of the Catholic Monarchs to pay Antonio de Arévalo the cost of hauling a supply of drinking water to the Grandcanarians who were to be deported by royal order, for not having authorized such expense.

Antonio M. López Alonso

References

- Ladero Quesada, M. Á. (1966). “Las cuentas de la conquista de Gran Canaria”, Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos, vol. 1, núm. 12, pp. 11-106. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (España): Cabildo de Gran Canaria.

- Lobo Cabrera, M. (2011). Las “princesas” de Canarias. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (España): Anroart Ediciones, S.L.

- Suárez de Quintana, Fr. J.; González-Sosa, P. (2006). Relación Genealógica de Fray Juan Suárez de Quintana. Transcripción, introducción, notas e índice onomástico por Pedro González-Sosa. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (España): Obra Social de La Caja de Canarias.