A view of Teguise town (Lanzarote) in 2016 from Mount Guanapay. Named Gran Aldea (Great Village) by Europeans in the fifteenth century, it was the capital of the Seigneury of the Isles of Canaria and the scene of residents insurrection against Inés Peraza and Diego de Herrera’s rule that gave rise to Cabitos’ Inquiry (source: PROYECTO TARHA)..

[…] and we as people few and poor, miserable, ignorant, living on this island, poor having nothing to provide us or feed us but the skies and goat herds, and we have no other property or income to live on. For, Lord, if we pick bread one year, two years we do not pick it, and so we are living on this land, in our misery and poverty, and they take the above said tax from us […]. And about that all, the above said Lords Diego de Herrera and Doña Inés, his wife, are not contented […] every day they do us more harm, taking us out of our homes, making us abandon our wives and children, taking us by force against our wills to other islands of infidels where many of us died and still die and make us keep towers and fortresses […] not wanting neither to give nor to pay us any wage […] and we dare neither to tell them nor to repeat to the above said Lords nothing of such grievances they do to us because of the great fear of them we have until make it known to Your Highness, to whom we plead with loud voices, as very miserable and aggrieved people, that Your Highness remedy us with justice, for, Lord, we are isolated on the islands, on the said island of Lanzarote, which is far apart from the kingdoms of Spain, westwards in the sea. [1]Aznar Vallejo (1990, pp. 173-174) –adapted from old Castilian by PROYECTO TARHA–.

Promoters of this plead never imagined that their requests would give rise to the most important public file kept on the conquest of the Canaries.

In August 1475, the residents of Lanzarote, descendants of Maho indigenes and French-Norman and Castilian conquerors who had invaded the island at the beginning of that century, along with new residence settlers, begged Notary Juan Ruiz de Zumeta to write in their behalf this urgent letter to Fernando V the Catholic, consort King of Castile, denouncing the abusive practices of the Lords of the island, Doña Inés Peraza and her husband, Diego García de Herrera, and requesting political and administrative conversion of the island to the royal domain, thus to direct governance by the Crown, which in practice amounted to claim the abolition of the Seigneury of the Isles of Canaria. The messengers appointed to deliver the letter with a thick sheaf of documentary evidence and represent the Council of the island were two Lanzarote natives: Juan Mayor and Juan de Armas.[2]Aznar Vallejo (1990, pp. 170-172).

Great dangers were not scarce during the journey of both prosecutors: just before arriving at Córdoba, some members and agents of the seigneurial family stole all the documentation in addition to abduct and lock them into an estate of the Herrera-Peraza family in Huévar, west of Sevilla, finally being rescued by a senior official of the Court, Dr. Antón Rodríguez de Lillo.[3]Aznar Vallejo (1990, pp. 223-224).

Original of the Virgin of the Elms (14th century) presiding the Corral de los Olmos (Patio of the Elms), an enclosure where the Cabitos’ Inquiry was carried out and which occupied the space of the current Virgen de los Reyes square in Sevilla, where a copy of this statue can be seen placed in a niche of the Giralda (source: Wikimedia Commons). .

Esteban Pérez de Cabitos, inquirer judge

Following the request of their island subjects, the Catholic Monarchs ordered to investigate who was the rightful owner of the island of Lanzarote, as residents insisted that such possession was ultimately subjected by law to the Crown of Castile.

The monarchs directly entrusted this mission to Esteban Pérez de Cabitos, resident in the Sevillian collación –parish– of Triana, being named inquirer judge for this purpose. Full data on this character and why had he been chosen are unknown, but certainly he must have been trusted by the Crown, being rewarded by the execution of this order with the property of the stream and spring of the Rocinas –nowadays known as Rocina, bordering El Rocío (Huelva), in addition to the position of Higher Mayor of Gran Canaria. [4]Archivo General de Simancas –catalogue numbers RGS,LEG,147611,732 & RGS,LEG,147803,42–.

Dismissing protests from seigneurial prosecutor, Alfonso Pérez de Orozco, who had demanded Pérez de Cabitos to travel to Lanzarote to better fulfill his duties as inquirer, the investigation was conducted entirely in Sevilla, between December 1476 and April 1477, inside the Corral de los Olmos, an enclosure that housed the municipal offices leaning on the tower -the old minaret known years later as Giralda– of the cathedral of Santa María la Mayor. Cabitos refused alleging, among other reasons, avoidance of possible attempts to bribe him, although we might suppose the inquirer simply did not want to take a trip in which the risk of losing his life was quite high, given the interests at stake.

Witnesses and voices: the interrogations

We have pointed out before, unlike chronicles and histories about the conquest in which the protagonists acquired an almost legendary corporeality, public documents provide a much more realistic view on them, and the Cabitos’ Inquiry is a great sample of it. Across its manuscripts not only the words of the appearing witnesses, some of them known by ethnohistorical sources, do parade but also the documented voices of Kings Juan II, Enrique IV, Isabel I, Fernando V, the Count of Niebla, Maciot de Béthencourt, Diego García de Herrera, Inés Peraza, Fernán Peraza the Elder and Guillén de las Casas, among others. And it is regrettable the irremediable silence that death and time have dropped on the knowledge, to a greater or lesser extent, these and other characters certainly hoarded on the truth of those events and the indigenous culture.

The eleven witnesses presented by the council of Lanzarote and the Crown were subjected to a legal interrogation composed of nine questions, plus another nine required by the Seigneury side. These eleven individuals were:

- Juan Rodríguez de Gozón: merchantman.

- Antón Fernández Guerra: King’s cómitre (galley overseer).

- Pedro Fernández Chichones: merchantman.

- Juan García Bezón: King’s cómitre.

- Diego de Porras: merchantman.

- Juan Rodríguez de Cubillos: King’s cómitre.

- Juan Ruiz de Zumeta: King’s Scribe, resident in Lanzarote. According to Brother Juan de Abreu Galindo, he signed the Act of Zumeta.

- Fernán Guerra: almogávar (scout) and interpreter, resident in Lanzarote. A character of paramount importance to the conquest of Gran Canaria, as we eventually discuss in a future post.

- Juan Bernal: resident in Lanzarote, being among those men who Inés Peraza ordered to arrest during neighborhood protest.

- Juan Mayor: native of Lanzarote, residents prosecutor and habitual character in the chronicles of the Canary Islands appearing as an interpreter of the indigenous language.

- Juan Íñiguez de Atabe: Chamber Scribe to the Catholic Monarchs. Seizer of Lanzarote during two years of the reign of Juan II of Castile.

In defense of its rights, the Seigneury of the Isles of Canaria presented twelve witnesses, who were subjected to an interrogation made of no less than forty-one questions. Their names were:

- Manuel Fernández Trotín: moneychanger and merchantman. During the royal conquest of Gran Canaria he would supply Captain Juan Rejón’s camp.

- Antón de Soria: resident in Sevilla.

- Gonzalo Rodríguez: mariner.

- Diego Martínez: carpenter who participated in the building of the Tower of Gando.

- Fernán Alfonso: helped to deliver supplies to the Tower of Gando.

- Diego de Sevilla: merchantman.

- Juan Bocanegra: resident in Sevilla.

- Antón Benítez: mariner.

- Pedro Tenorio: biscuiter.

- Martín de Torre: resident in Sevilla.

- Antón de Olmedo: coalman.

- Álvaro Romero: priest.

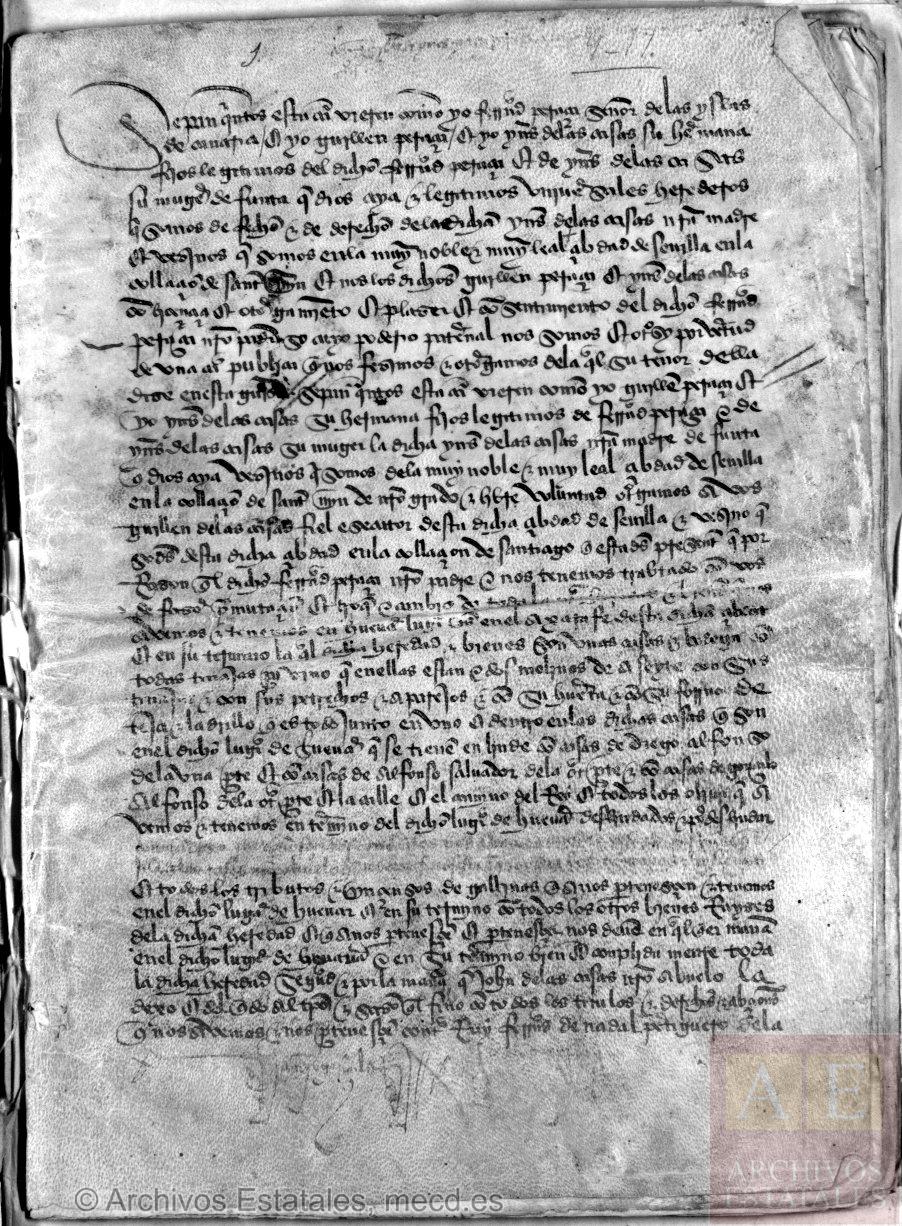

Front of the first folio of one of the documentary evidence submitted by the Seigniory of the Isles of Canaria before Judge Cabitos: the deed of exchange in 1445 of the rights Guillén de las Casas held on the Archipelago by an olive-producing manor owned by Fernán Peraza the Elder and his children Guillén Peraza and Inés de las Casas, later known as Doña Inés Peraza (source: PARES – Archivo General de Simancas – catalogue number CCA,DIV,9,17).

A perfect excuse

Embroiled the Crown of Castile in open war with the Kingdom of Portugal for possession of the Castilian throne and dominion of the North-African Atlantic, Cabitos’ Inquiry gave to King Fernando V the perfect excuse to finally take control of the conquest of the Canary Islands, weighed down by both the military incapacity the Seigneury and its ambiguous relationship with the Portuguese Crown –Inés Peraza and Diego de Herrera had married their eldest daughter to Diogo da Silva, a trusted man of the Portuguese throne and former adversary of the Lords– and, on the way, dismantle the small but diplomatically dangerous realm of the Herrera-Peraza.

Indeed, in the late summer of 1477, concluded the investigation and studied the case, a committee of three royal councilors gave their views to Queen Isabel I the Catholic who, with her husband, would make the final decision: the Lords would retain the ownership of the islands already taken but the Crown would expropriate them the right to conquer the rebellious lands in exchange for a compensation fixed at five cuentos -millions- of maravedís.[5]Aznar Vallejo (1990, pp. 20-21).

One can imagine that this decision, which only benefited the interests of the monarchs, must have fallen like a bucket of cold water on the residents of Lanzarote, who not only have to endure the Lords’ tyranny but now also foreseeable retaliation by Doña Inés Peraza. But King Fernando even knew how to capitalize this circumstance: every conquest needs settlers and Gran Canaria –and La Palma and Tenerife afterwards– would be a good refuge for the islanders offended by the Lords. Collaboration was the only hope they had left.

The manuscripts

The oldest copy of the record of Cabitos’ Inquiry –indeed, coeval to process– was drafted by scribe Diego Fernández de Olivares and it is preserved in the Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial (Madrid), catalogue number RBME X-II-26 and titled Información hecha por comisión de los Reyes Católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel, sobre a quién pertenece la isla de Lanzarote y la conquista de las Canarias (Information made by commission of the Catholic Monarchs Fernando and Isabel, on who owns the island of Lanzarote and the conquest of the Canaries). Unfortunately, the digitization of this important file is neither free nor downloadable.

Part of the original manuscripted proofs belonging to the file is lost and the rest is kept in a number of repositories such as the Archivo General de Simancas, digitally accessible through PARES website.

Recommended editions

We think of it as an essential purchase for anyone wanting to study in depth the ancient history of the Canary Islands the complete edition published in 1990 by Professor Eduardo Aznar Vallejo under the title Pesquisa de Cabitos (Cabitos’ Inquiry). However, there are two previous editions that are publicly available for digital download:

- The documentary part of the Inquiry, included in the second volume, published in 1880, of the Estudios históricos, climatológicos y patológicos de las Islas Canarias, by Dr. Gregorio Chil y Naranjo, founder of El Museo Canario.[6]Chil y Naranjo (1880, pp. 518-632).

- The witness part, inserted in the book Carácter de la conquista y colonización de las Islas Canarias, published in 1901 by Professor Rafael Torres Campos.[7]Torres Campos (1901, pp. 121-206).

References

- Aznar Vallejo, E. (1990). Pesquisa de Cabitos. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria – Madrid: Cabildo Insular de Gran Canaria.

- Chil y Naranjo, G. (1880). Estudios históricos, climatológicos y patológicos de las islas Canarias. Historia. Tomo 2. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Imprenta La Atlántida.

- Torres Campos, R. (1901). Carácter de la conquista y colonización de las Islas Canarias. Madrid: Imprenta y Litografía del Depósito de la Guerra.