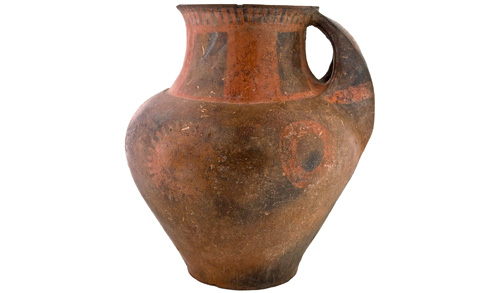

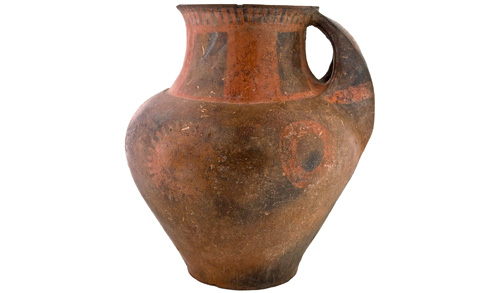

Indigenous pitcher found at Agüimes (Gran Canaria), kept at El Museo Canario, catalogue number 260, featuring two shapes presumably depicting a sun and a solar eclipse (source: El Museo Canario).

To the Canarian historiography the legendary episode of the raid over the indigenous village of Agaldar (Gran Canaria) by Portuguese captain Diogo da Silva de Meneses is a well-known one.

After landing under cover of the night, the Luso-Castilian expedition, composed of about two hundred troops, tried unsuccessfully to raze the islander village at dawn getting trapped in turn by a threefold contingent of fighting men. Sieged inside a large facility surrounded by high walls of dry stone, the invaders remained locked there for two days and one night until the Guanarteme -chieftain- of Agaldar, uncle of the future Fernando Guanarteme, agreed to parley with Diogo da Silva. Chronicles tell that after berating the Portuguese his audacity and contravening the desire of his own warriors to end the lives of all the besieged, the indigenous leader pretended to fall into the hands of the Europeans to facilitate their release, who as a result of this supposedly pious act began to name him Guanarteme the Good.

But here we are not interested in describing the different versions of this story, from the shortest, most sober offered in the Cronica Ovetensis to the novelistic rewriting by Leonardo Torriani, but to draw attention to a curious datum provided by this Cremonese engineer in the baroque speech he makes the islander leader pronounce. This particular passage is as follows:

(más…)

Más / More...