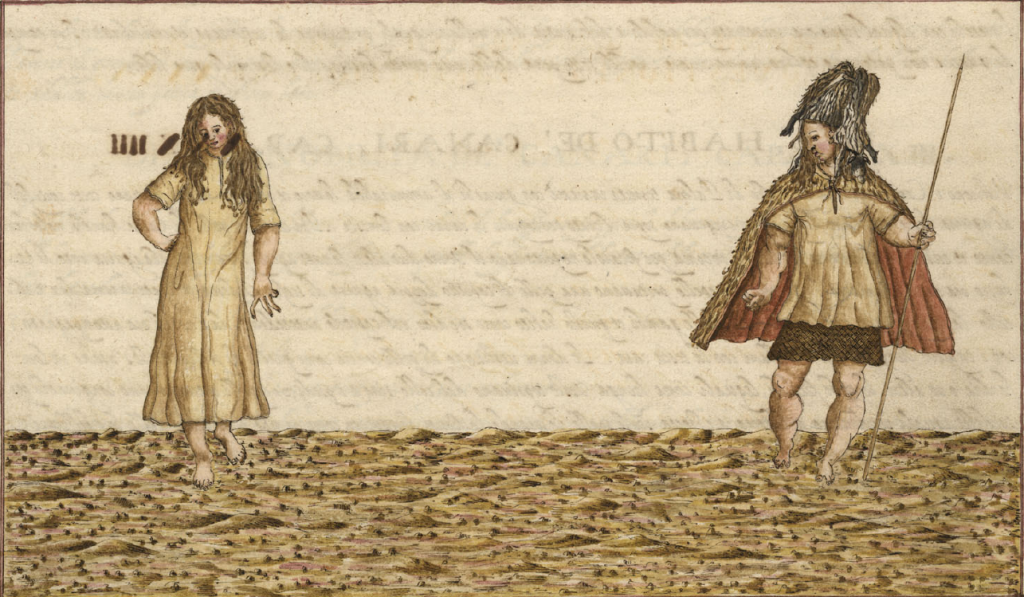

Indigenes of Gran Canaria as per recreation by Leonardo Torriani (16th century) (source: Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra, catalogue number Ms. 314, folio 36v.)

In thriving societies, population control is a topic that inspires debates subjected to ethical, moral and religious considerations, often distorted by the conjuncture of a welfare state that is supposed to hold an indefinite durability. But in human communities subject to limiting factors, whether temporary or permanent, either of productive –scarceness of drinking water, arable land and / or pastures–, environmental –plagues, epidemics, droughts, floods, fires– or political nature –wars– the survival of these could depend largely on the application of restrictive measures on the birth rate, while it is true that, in many cases, these measures seek to promote the interests of the privileged classes by means of eugenics or selection of individuals deemed most convenient.

In the Canarian historiography, specifically in Gran Canaria, the so-called statute on killing the girls is paradigmatic, so named by its best known reference, Brother Juan de Abreu Galindo:

There were on this island many men and many more women, said fourteen thousand men altogether, and seeing how they were expanding and that maintenances were missing, and not enough fruits were picked for their sustenance, to not live in hardship, on coming to consultation and congregation they called Sabor, they agreed and made a statute to kill all females who were born thereafter, as long as they were not the first births women did, for such wombs they reserved for their preservation, and they made up the fruits that the land would produce and they did not lack them as it had been years ago.[1]ABREU (1848), p. 107.

This statement is endorsed by the account of Pedro Gómez Escudero who also wrote that there were ten women for every man, clarifying that fourteen thousand was the number of indigenous families residing in Gran Canaria.[2]MORALES (1978), p. 440.

However, Leonardo Torriani, Abreu Galindo contemporary, offers a version in which the statute is applied to both genders:

A few years before the isle of Canaria was conquered, whether due to a fruitful influence of the sky or because people were living with health in a space of many years, they went on being born without deaths keeping such pace. Thus people expanded in such quantities that crops were no longer enough to support themselves, and began to suffer famine, to the point that, forced by necessity, not to perish all, they made an inhuman law, to kill all the children after the first delivery; in whose cruelty they were only equal to themselves.

Then the Cremonese engineer adds thoughtfully:

Although this law was contrary to human mercifulness, although considering its purpose, it is very merciful, because it is also a virtue losing a part to save the whole. The desire to immortalize his posterity forces man to do things contrary to the customs and to reason;[3]TORRIANI (1959), p 115.

Population control or an eugenic measure?

We should raise the question of whether the statute on killing the girls represents a simple case of population control or also constitutes an eugenic practice imposed by the ruling elites to the whole ancient Grandcanarian indigenous society, as Abreu Galindo’s testimony clearly states that the decision was taken by the Sabor or council of noble islanders. Let us start by analyzing the face-off between the versions offered by Abreu Galindo/Gómez Escudero and Torriani.

The elusive friar asserts that all females were to be killed except those born in a first delivery, so it is inferred that all men birthed by a single woman were to keep their lives, regardless of their number. Consequently, this is unlikely to be a very effective measure of population control to deal with a time of famine, unless the ancient ones gave priority to have many fighting men opposing an already abundant female population, though perhaps being this an understandable decision to face the constant threat of European incursions.

Instead, Torriani witnesses a possibly more rational choice from the standpoint of pure population control: to allow the survival of a single neonate per woman, regardless of his/her sex.

In any case, the decision attested by Torriani of allowing a single birth per woman or, if we believe Abreu Galindo, the survival of a single girl per woman in labor does not seem arbitrary, but probably was aimed at the preservation of the indigenous noble lineage through their particular droit du seigneur, as described by, among others, Chronicler Andrés Bernáldez:

When they had to marry a virgin, they put her, after concerting the marriage, certain days in vice, to get fat; and she went out of there and they married them; and the knights and noblemen of the village came before her, and she had to sleep with one of them before the bride, whoever she wanted to. And if the knight got her pregnant, the child was born a knight; and if not, the children of her husband were common. And to see if she got pregnant, the husband did not reach her until know it certainly via purgation.[4]MORALES (1978), pp. 515-516. This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

Abreu Galindo as well:

Among principal and noble folk there was a custom whenever they wanted to marry the maidens to have them laid thirty days and they gave them mixtures made of milk and gofio and other foods they used to eat indulging them to got them fat. And so it was with the other maidens. And before the maid gave herself to her spouse and husband the night before he gave and handed her to the Guanarteme to give him the prime of her virginity, and if he accepted, to give him the prime and if not she gave it to the Faican, or to the most favourite, as long as he was a noble, not marrying them skinny because they said they had a small belly, and too narrow to conceive.[5]ABREU (1848), pp. 96-97. This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

Thus, the only born during the validity of the statute would be individuals candidates to join the privileged class after reaching a certain age at which they would be subjected to confirmatory tests of nobility, in the case of men, or possibly would join the institution of the harimaguadas, in the case of women.[6]ABREU (1848), pp. 89, 97.

Antonio M. López Alonso

References

- Abreu Galindo, Fr. J. de. (1848). Historia de la conquista de las siete islas de Gran Canaria. Imprenta, Lithografía y Librería Isleña.

- Morales Padrón, F. (1978). Canarias: Crónicas de su conquista. Ayuntamiento de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria – El Museo Canario.

- Torriani, L. (1959). Descripción e historia del reino de las islas Canarias antes Afortunadas con el parecer de sus fortificaciones. Traducción del Italiano, con Introducción y Notas, por Alejandro Cioranescu. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Goya Ediciones.