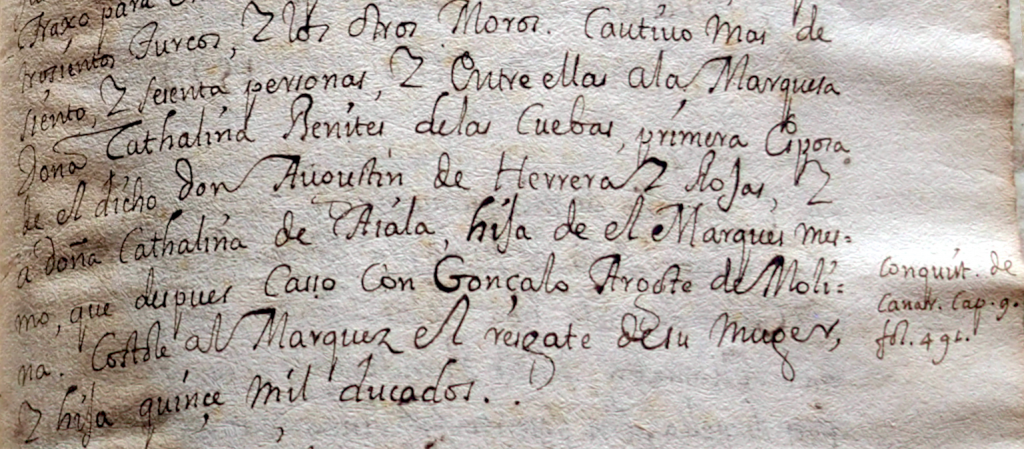

Fragment of manuscript COL MAN 1, [Book III, Chap. X], f. 221(201)r (source: Archive and Library of Casa de Colón –Las Palmas de Gran Canaria–).

The difficulty involved in finding new narrative sources or public documents dealing with the conquest of the Canary Islands –and which also help to shed light on the many obscure areas throughout this complex historical period– is sometimes offset by the discovery of small informational gems such as the two we present in this post.

Both are included in the unpublished manuscript COL MAN 1, preserved in the Archive and Library of Casa de Colón (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria), which was acquired from an anonymous private owner in 2020 by the Cabildo de Gran Canaria and presented to the public in 2021. The volume, as we explained in our previous post, contains an expanded version by its author, Fray José de Sosa (1646–c. 1730?), of his Topography of the Fortunate Island Gran Canaria.

A lost chronicle or history?

The first of these new findings is the reference to what appears to be one of the lost chronicles or histories of the Archipelago. Its context is the following fragment, which, while recording the assault on Lanzarote in 1586 by Murat Reis –hispanicized as Morato Arráez– supposedly in retaliation for the raids on Barbary orchestrated by the island’s marquis, Don Agustín de Herrera y Rojas (?-1598), Sosa notes that the Ottoman corsair[1][Book III, Chap. X], fol. 221(201)r.:

He captured more than one hundred and sixty people, among them the Marchioness Doña Cathalina Benites de las Cuebas, first wife of the said Don Agustín de Herrera y Rojas, and Doña Cathalina de Aiala, daughter of the marquis himself, who later married Gonçalo Argote de Molina. The ransom of his wife and daughter cost the marquis fifteen thousand ducats[2]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA..

This information, which we do not find in any of the other known Canarian chronicles or histories of the period, is supported by Sosa with the following bibliographic reference in a marginal note:

Conquist[a] de Canar[ias], cap. 9, fol. 496.

We are not aware of any Conquista de Canarias contemporary to the Franciscan historian that addresses this matter or contains at least 496 folios or even pages, since at the time the former term was also used interchangeably for the latter. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that Sosa is referring to a source now lost, perhaps one of those attributed respectively to Doctors Antonio de Troya and Alonso Fiesco, or even –though it is unlikely he would have cited himself– the one prepared by the aforementioned Gonzalo Argote de Molina, all of which, as we have noted, remain missing to this day.

Hita manira cura

Despite the undeniable abundance of words from the ancient Canarian language –generically known as guanchismos– present in the archipelago’s toponymy, the centuries-long oblivion of their meanings, combined with the scarcity of complete phrases or commonly used expressions translated, and the absence of lexicons or other contemporary monographs that clarify them semantically and grammatically, make the scientific recovery of this cultural heritage extremely difficult. Nevertheless, hope is not lost that one day a Rosetta Stone may be found to help unearth and revive the voices that dozens of past Canarian generations used and shaped for at least a millennium and a half in their daily lives, to give form and meaning to the universe they inhabited both earthly and spiritual.

For now, we have no choice but to settle for the remnants of that rich fabric, invariably distorted by the imprint of the colonial filter and by the erosion caused by time and the evolution of customs and practices. Today we present our discovery of one of these promising fragments, once again, in the work cited above.

In the third chapter of the third book[3]fol. 185(177)r. of the expanded version of Sosa’s Topography, the author reproduces a passage from his earlier draft that describes a custom of the ancient Grandcanarians, one already known from other documentary sources:

If they lacked water for their breads [sic, crops], they would ask God through devout and virtuous persons, who would leave their homes where they lived secluded, preserving purity and chastity, and go to high places designated for such petitions. These were two inaccessible crags, one called Tirma and the other Magro […][4]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA.

But in a marginal note he adds a clarification, which Sosa himself indicates –by means of a reference mark– should be inserted immediately after the word petitions:

[…] sometimes and in others they went to the sea instead. To which, striking with sticks, they would devoutly say Hita manira cura «Lord, give us water» and most of the time, seeing their innocence, God would come to their aid generously and mercifully[5]This translation by PROYECTO TARHA..

It is clear that Sosa, a Franciscan friar, seeks here to reinforce the argument –scattered throughout his work– that the ancient Canarians were not idolaters but gentiles (pagans), interpreting the old ritual as a supplication to a supreme being without any iconic representation, which the innocent devotees were not yet able to fully comprehend, having not received the teachings of the Gospel.

Fragment of manuscript COL MAN 1, [Book III, Chap. III], f. 185(177)r (source: Archive and Library of Casa de Colón –Las Palmas de Gran Canaria–).

Unfortunately, Father Sosa does not specify the source of his information, which makes it even more difficult to grant authenticity or accuracy to his testimony. Nevertheless, regardless of the philological and linguistic analyses that may be carried out on this matter –and which we are not qualified to undertake on our own– it is worth noting that, aside from the well-known distortion introduced by the Hispanicization of native phonemes, the segmentation of the words that make up the aforementioned expression may also have been altered.

Thus, and only as a suggestion, the word aman –meaning ‘water’ and common to continental Tamazight dialects– appears to be present in the reformulated segmentation hit aman ira cura. Furthermore, the initial ‘h’ should not be understood as silent as in modern written Spanish but aspirated, as was customary at the time and, consequently, in the writings of Fray José de Sosa.

We encourage specialists to share their interpretations and observations in our comments section.

11 comments on “A new phrase in the Canarian language and a reference to an unpublished "Conquest of the Canaries"”